From collection Jesup Library Maine Vertical File

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Search

results in pages

Metadata

Bar Harbor: The Hotel Era 1868-1880

Bigry

UNITED HISTORICAL SECURITY

A.D.

Maine Historical Society

Newsletter

B.H Hotels 4 pictures

B.H Stramboots plo2 ap107

Footiate p. 119

Vol. 10 No. 4

May, 1971

MAINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Incorporated 1822

OFFICERS

Roger B. Ray President

Miss Elizabeth Ring Vice President

Harry W. Rowe Secretary

Arthur T. Forrestall Treasurer

STANDING COMMITTEE

Terms expire 1971

Miss Hilda M. Fife

James S. Leamon

James C. MacCampbell

Martial D. Maling

Linwood F. Ross

Terms expire 1972

Mrs. Edwin L. Giddings

Miss Edith L. Hary

H. Draper Hunt, III

William B. Jordan, Jr.

Mrs. William J. Murphy

James B. Vickery, III

Terms expire 1973

Robert G. Albion

Mrs. William E. Clark

Donald L. Philbrick

Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr.

Herbert T. Silsby, II

Samuel S. Silsby, Jr.

STAFF Director

Gerald E. Morris

Curator of Manuscripts

Thomas L. Gaffney

Reference Librarian

Mrs. Shirley E. Welch

Cataloger

Miss E. Virginia Gronberg

Registrar & Secretary

Mrs. Shirley L. Barnes

Library Assistant

Mrs. Esta Astor

Maintenance & Exhibits

Charles D. Heseltine

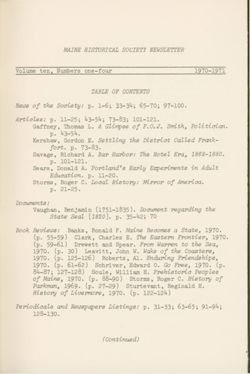

MAINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER

Volume ten, Number four

May, 1971

Published quarterly at 485 Congress Street

Portland, Maine 04111

ANNUAL MEETING

The 149th Annual Meeting of the Society

will be held in Lewiston at Bates College on

the sixteenth of June. The campus is parti-

cularly attractive at that time of year, and

we hope that many of you will be able to come

and enjoy the hospitality provided by the

Bates College community.

Bring a guest if

you like. None of the sessions are closed to

the public, even though voting must be reserv-

ed to members.

As announced previously, Charles E. Clark,

professor of history at the University of New

Hampshire will be the guest speaker. Dr. Clark

has chosen as his topic: Beyond the Frontier:

an Environmental Approach to the Early History

of Maine.

An exhibit of watercolors and acrylics by

Thomas Crotty of Freeport will be on view during

the entire day, thanks to Miss Synnove Haughom,

Curator of the Treat Art Gallery, who arranged

to have the show extended for our visit.

Mr. Craig Canedy, director of foods ser-

vices at Bates, has prepared a wonderfully varied

menu for those who wish to take advantage of the

buffet luncheon. Tickets for the luncheon are

priced at $3.75, and reservations must be made in

advance. All members of the Society will receive

reservation cards with return envelopes well in

advance of the meeting. A registration fee for

the sessions will not be required either for mem-

bers, or for their guests.

Program Schedule

10:00-11:00

LITTLE THEATER LOBBY

Registration. Coffee &

Doughnuts.

TREAT ART GALLERY An Exhibit of Watercolors

and Acrylics by Thomas

Crotty of Freeport.

11:00-12:00

LITTLE THEATER

Business Meeting

Prize Essay Contest Awards.

12:30

CHASE HALL DINING ROOM

Buffet Luncheon:

Six Salads Ham Turkey

Roast Beef Seafood New-

burg Relishes Cheeses

Strawberry Shortcake

2:00

LITTLE THEATER

Dr. Charles E. Clark

"Beyond the Frontier: an

environmental approach

to the early history of

Maine.

3:00

Twenty minute discussion

period.

3:30

New Standing Committee

Organization Meeting.

Election of Officers.

In response to a number of requests, we have had separates

run for the 1755 map, "A Plan of Kennebeck and Sagadahock

Rivers, 99 by Thomas Johnston, which appeared on pages 80 and 81

of the February Newsletter. copies are available from the

Society for $1.50 postpaid plus 8 sales tax for Maine resi-

dents.

The unusual clarity achieved on this reproduction can be

credited to the skill and tireless quality control of the staff

at Casco Printing Company.

98

NEW MEMBERS

From MAINE Auburn: Willis C. Strout Augusta: Mrs. Henry

L. Doten, Mrs. Earl C. Goodwin Bangor: Mrs. Clyde M. Lougee

Bar Mills: Miss Dorothy S. Furber, Mrs. Floyd R. Hannaford

Brunswick: Mrs. Thomas Means Camden: Ralph E. Cook Cape

Elizabeth: Donald R. McNeil, Mrs. William Zrioka Chebeague

Island: Miss Donna Miller Hampden: Mrs. John C. Heath Hollis

Center: Mrs. Edith W. Dow Lewiston: Mrs. Philip Archambault,

Mrs. Merriam D. Irish, Mrs. Alton Stevens Machiasport:

Charles B. Jones Orono: Richard S. Davies, Sister Adele

Plachta Pemaquid: Mrs. Edward J. Fertig Portland: John

Cahouet, Mrs. Gladys R. Donatelle, Stephen Hyde Scarboro:

Miss Josephine D. Berry South Berwick: Miss Marie A. Donahue

South Portland: Mrs. John J. Devine, Jr., , Miss Christine C.

Gray, Craig Hebert, Roger Hetstrom South Windham: Charles C.

Legrow West Baldwin: Mrs. Roderick Henderson West Paris:

Clarence R. Reid Wiscasset: William H. Soule Yarmouth: Miss

Elaine S. MacLeod, Mrs. Howard 0. Sturges

Other States MASSACHUSETTS Concord: Mark W. Biscoe

NEW YORK Hastings-on-Hudson: Raymond H. Fogler PENNSYLVANIA

Lemoyne: H. M. Eaton UTAH Salt Lake City: Miss Mary C.

Sewall WASHINGTON Seattle: Gordon Jackins

CORPORATE MEMBERS: Casco Printing Company.

The following members were appointed by President Ray to

serve on the Nominating Committee to fill Standing Committee

vacancies occuring in June, 1971: Edward S. Boulos, Jr., James

S. Kriger, Mrs. William J. Murphy, Roger C. Taylor, and Philip

S. Wadsworth. The Committee elected Mrs. Murphy chairman.

99

FRIENDS OF MAINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

We are pleased to announce the creation of a special fund

for the purpose of purchasing museum artifacts and manuscripts

which will be called the Friends of Maine Historical Society

Fund.

Although a modest amount of money is available for the

purchase of books from the Society's restricted funds, there

has never been an established fund upon which to draw for the

regular acquisition of museum objects and manuscripts.

The possibility of developing an occasional operating

surplus, which could be used to accomodate special purchases

from time to time, has all but been eliminated owing to this

country's prolonged inflationary period and to staff addi-

tions brought about by the pronounced increase in the use of the

Society's services.

The Friends of Maine Historical Society has the advantage

of removing such purchases from operating expenses, enabling

the Society to receive cash gifts for the specific purpose of

acquiring desirable Maine items when they appear on the open

market.

We earnestly hope that you will give this new fund your

thoughtful consideration. Nothing could be of more help in

trying to stem the alarming exodus of Maine materials from

this State.

All contributions are tax deductible and should be

addressed to:

Director,

Maine Historical Society

485 Congress Street

Portland, Maine

100

COMMENT

T.ROBERTS

Agamont House

Prologue

Samuel Champlain was the first European to venture near

the shores of Mount Desert Island, and it was that French sea

captain who named the mountainous isle "isle des monts deserts.

11

Champlain did not go ashore, but some later Frenchmen did. In

1613, less than a decade after Champlain's visit, a short-lived

Jesuit colony, Saint Saviour, was established near present-day

Southwest Harbor. Many years then passed quietly until, in

1688, Louis XIV granted Mount Desert and environs to Sieur la

Mothe de Cadillac, a self-styled nobleman who eventually

founded Detroit. He appears not to have settled at Mount

Desert, and, except for a few wandering Indians, the island

remained uninhabited until the 1760s.

In the early sixties, many families emigrated from Cape

Cod and Cape Ann to points north. A few of these settled at

Mount Desert, founding several isolated villages and hamlets

along the shores of the island, part of which then was owned

by Sir Francis Bernard, the Governor of Massachusetts. When

the Revolutionary War broke out, however, Bernard lost his

land, and the several scattered settlements were consolidated

as Mount Desert Plantation.

After the war, in 1785, the General Court of Massachusetts

returned one-half of Mount Desert to John Bernard, the former

governor's heir, and the other half of the island soon was

granted to Marie Therese de Gregoire, a granddaughter of the

enigmatic Cadillac who now claimed her alleged inheritance.

Meanwhile, the inhabitants of Mount Desert Plantation voted

to divide the plantation into two distinct towns, Mount Desert,

which would encompass the Bernard Grant, and Eden, which would

bring together under one government the villages on the east-

ern shore--Hulls Cove, Salisbury Cove, West Eden, Eden proper,

and East Eden.

East Eden was an insignificant part of the Town of Eden

as the 19th century dawned, but within a few decades, East

Eden, more popularly known as Bar Harbor, would emerge as one

of America's best known "watering places." The early inhab-

itants of Bar Harbor, the Higginses, the Hamors, the Robertses,

the Rodicks, and the Lynams, farmed, fished (the Rodicks had

weirs near Bar Island in Frenchman's Bay), and sailed the high

seas. Tobias Roberts owned a general store and was the resi-

dent money-lender. A later arrival, Jacob Suminsby, was the

local shipbuilder. They all were hardy souls, living strenu-

ous, perhaps barren, lives. But all of this was soon to change.

Beginning in the 1840s, Bar Harbor was discovered by the

Hudson River artists, most notably by Thomas Cole and Frederick

Church. With these and other artists as publicists, Bar Harbor

soon was attracting a substantial resort clientele. At first

the artists and the other early resorters (or "rusticators,"

such as New York lawyer Charles Tracy whose daughter Frances

later married Morgan) boarded with local families, the

artists preferring the Lynam Homestead at Schooner Head near

Bar Harbor. Within a few years, however, these make-shift

facilities proved inadequate, and in 1855 Tobias Roberts erect-

ed the Agamont House, Bar Harbor's first hotel. Other inhab-

itants followed his lead, and after the Civil War ended, hotel

construction increased dramatically. Regular steamboat service

to the resort was begun by the steamer Lewiston in 1868, clear

evidence that the resort was growing in popularity.

Along with the hotels and boarding houses, Bar Harborites

built their first church, the Union Meeting House (the "white

church"). Slowly, the hamlet was becoming a town. By 1870

102

there were fourteen hotels at Bar Harbor, of which David Ro-

dick's Rodick House was the largest, several shops, and a

considerable number of new, year-round homes. All of Bar

Harbor's original settlers now were engaged in the resort

trades, and with increasing speed, the inhabitants of Eden's

other villages were gravitating toward Bar Harbor, eager to

share in the new-found prosperity. The old order was rapidly

changing, in the opinion of most for the better.

The resort's future brightened even more in the late

sixties when several "boarders" left their hotels and boarding

houses to build their own "cottages." An element of perma-

nence and stability was being introduced at Bar Harbor. Bos-

ton merchant Alpheus Hardy was the first to build, by the sea

of course, and other Bostonians followed suit--the wealthy

Montgomery Sears, William Minot, the Welds and the Hales, to

name but a few. A lone New Yorker, Gouverneur Ogden, also

joined the movement, and more New Yorkers would follow. But

the social ascendency of these cottagers was yet to be real-

ized, and the decade of the seventies belonged to the hotels.

For Bar Harborites, the hotel era had arrived.

The Hotel Era

Local residents invested large sums in the resort trades.

David Rodick and sons invested $12,000 in their hotel enter-

prise, and Tobias Roberts was not far behind. Richard Hamor

had built the Bay View House in 1868 and was soon to build the

Grand Central, the town's second largest hotel. Other pro-

prietors invested considerably less, but as a whole, hotel

construction was a great boon to Bar Harbor's economy. [1]

All of this building required capital. There was no bank

in Bar Harbor, but there were several sources for the necessary

funds. Tobias Roberts still provided occasional loans, and he

had local competition. When A. J. Mills furnished his Kebo

House, he borrowed the money from Charlotte Higgins, proof that

the fairer sex was not averse to timely investment. Furnish-

ings for the hotels generally were purchased at Bangor from

George Merrill. [2] Bar Harbor proprietors financed thousands

of dollars worth of furniture through Merrill. If more money

was needed for construction costs or furnishings, there was a

bank at Ellsworth, [3] and loans could be obtained from Monroe

Young, soon to be mayor of that city. Young had turned from

his Civil War task of finding substitutes for Edenites, to

proferring loans to Bar Harbor entrepreneurs. [4] Ellsworth

was also the site of the mills of J.H. and E.H. Hopkins, from

whom many Bar Harbor proprietors bought lumber, clapboards,

103

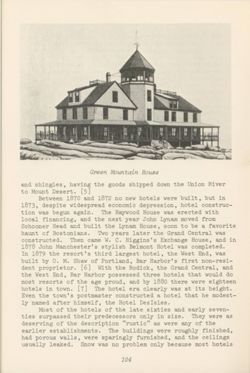

Green Mountain House

and shingles, having the goods shipped down the Union River

to Mount Desert. [5]

Between 1870 and 1872 no new hotels were built, but in

1873, despite widespread economic depression, hotel construc-

tion was begun again. The Haywood House was erected with

local financing, and the next year John Lynam moved from

Schooner Head and built the Lynam House, soon to be a favorite

haunt of Bostonians. Two years later the Grand Central was

constructed. Then came W. C. Higgins's Exchange House, and in

1878 John Manchester's stylish Belmont Hotel was completed.

In 1879 the resort's third largest hotel, the West End, was

built by 0. M. Shaw of Portland, Bar Harbor's first non-resi-

dent proprietor. [6] With the Rodick, the Grand Central, and

the West End, Bar Harbor possessed three hotels that would do

most resorts of the age proud, and by 1880 there were eighteen

hotels in town. [7] The hotel era clearly was at its height.

Even the town's postmaster constructed a hotel that he modest-

ly named after himself, the Hotel DesIsles.

Most of the hotels of the late sixties and early seven-

ties surpassed their predecessors only in size. They were as

deserving of the description "rustic" as were any of the

earlier establishments. The buildings were roughly finished,

had porous walls, were sparingly furnished, and the ceilings

usually leaked. Snow was no problem only because most hotels

104

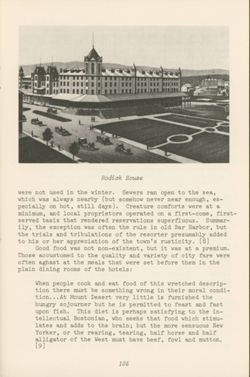

Rodick House

were not used in the winter. Sewers ran open to the sea,

which was always nearby (but somehow never near enough, es-

pecially on hot, still days). Creature comforts were at a

minimum, and local proprietors operated on a first-come, first-

served basis that rendered reservations superfluous. Summar-

ily, the exception was often the rule in old Bar Harbor, but

the trials and tribulations of the resorter presumably added

to his or her appreciation of the town's rusticity. [8]

Good food was not non-existent, but it was at a premium.

Those accustomed to the quality and variety of city fare were

often aghast at the meals that were set before them in the

plain dining rooms of the hotels:

When people cook and eat food of this wretched descrip-

tion there must be something wrong in their moral condi-

tion

At Mount Desert very little is furnished the

hungry sojourner but he is permitted to feast and fast

upon fish. This diet is perhaps satisfying to the in-

tellectual Bostonian, who seeks that food which stimu-

lates and adds to the brain; but the more sensuous New

Yorker, or the rearing, tearing, half horse and half

alligator of the West must have beef, fowl and mutton.

[9]

105

Fortunately for those displeased with the food and acco-

modations, local proprietors now offered their guests something

more than mere board and shelter. The cumbersome Atlantic

House provided croquet for its patrons, and owner J. H. Doug-

lass bought a piano for the Atlantic's music room. Most of

the hotels, including the Ash brother's Eden House, had teams

and drivers at the disposal of guests. The Saint Sauveur fur-

nished yachts and rowboats, and promised fresh fruits and

vegetables for "mealers." All hotels served the popular blue-

berry. [10] Even though there were as yet no esoteric entice-

ments that would magnetically draw the tourist to one hotel

in preference to another, an element of competition was being

introduced, and Bar Harbor's proprietors were gaining in busi-

ness acumen.

Most Bar Harbor hotels already were well known in Boston.

[11] So many Bostonians visited the growing resort that word

simply "got around." Another reason for such fame (or notor-

iety) was that a few proprietors understood the value of

advertising. For instance in 1875 the owners of the Rodick

House printed a descriptive pamphlet that promised the pros-

pective guest running water and guaranteed that reservations

would be honored under any and all circumstances. Rates were

$1.50 and $2.50 per day, board included, and the rates at the

smaller hotels and boarding houses were not significantly less.

Price differentiation had not yet reached an advanced stage of

development.

Independent advertising by the hotel proprietors helped

individual establishments build growing businesses, but more

significant in terms of the influx of resorters to Bar Harbor

was the existence of an increasing number of Mount Desert

"guidebooks," all of which devoted a majority of their pages

to extolling the beauty of Bar Harbor and vicinity. The rest

of the island was slighted, but this was only just, for Bar

Harbor now was the prime place of resort on Mount Desert.

Southwest Harbor was still frequented by many rusticators,

but its appeal was mostly to those who had been long settled

there, or to those who wished to escape the "noisy" atmosphere

of Bar Harbor's hotels. [12]

The first of the Mount Desert guides was privately printed

in 1867 by Clara Barnes Martin. An updated version was pub-

lished annually for the next several years by a Portland firm,

but the guide was very superficial. [13] A somewhat more

comprehensive guidebook was that of Benjamin F. DeCosta, first

published in 1868, which gave a less stilted protrayal of

resort life at Mount Desert. [14] Ezra A. Dodge, a native of

Ellsworth, also wrote a brief history and guide to the island

106

that was placed on the market in 1871. [15] All three authors

praised the beauties of Mount Desert, told people how to get

there, and suggested what they might see and do after they

arrived. The wide circulation of the guidebooks helped bolster

an already thriving resort economy. Other Bar Harbor and Mount

Desert guides appeared later, but the earliest ones were most

influential in terms of Bar Harbor's growth and development.

By the early seventies, it was easier than ever to reach

Bar Harbor. Trains connected nearby Bangor, on the Penobscot

River, to all the major population centers of the East, and an

expanding network of railroads made Bar Harbor accessible to

most of America. [16] Steamers plied regularly from New York

and Boston to Bar Harbor and Southwest Harbor. [17] The

Lewiston had the Bar Harbor run to herself until 1870, when

the Charles Houghton was placed on the Rockland-Sedgwick-Mount

Desert route. This challenge ended in failure, however. The

Ulysses, owned by the newly-created Rockland, Mount Desert and

Sullivan Steamboat Company, was somewhat more successful as a

competitor -- that is until she blew-up on January 10, 1878.

By 1876 there were four lines running steamboats to Bar Harbor,

carrying mostly passengers, but also serving as freighters for

local merchants and proprietors.

As the hotels prospered and expanded, and as new ones were

built, the steamers helped supply occupants for the ever-

increasing number of hotel rooms. But not all of those who

were greeted by the enthusiastic throngs on Bar Harbor's wharves

came to partake of the hospitality of local proprietors. Many

resorters now were returning to their own cottages, and others

came as guests of these very cottagers. Many such guests later

returned to build homes of their own and join the movement that

would culminate in the establishment of a viable summer "col-

ony 11

There was in the early seventies no cottage colony with a

social life separate from that of the boarders in the hotels.

The vast majority of resorters still lived in hotels and

boarding houses, [18] and the cottagers and boarders mingled

freely. [19] This is understandable for the early cottagers

were only boarders who desired more privacy, and not a breed

apart. It was not long, however, before differentiation be-

tween the groups markedly increased, in part because of a

change in the socio-economic make-up of the cottagers. During

the seventies more and more cottages were being built, and the

owners were increasingly drawn from the business and financial

classes. [20] The next logical development, and one that would

be realized fully in the late eighties and throughout the nine-

ties, would be the arrival of the millionaires, with a

107

sub-culture that

would make the

informal "mingling"

of the seventies

difficult if not

impossible to at-

tain. This al-

ready had happened

at Newport. [21]

But for the time

TIT

being, informality

and rusticity re-

mained the rule at

Bar Harbor.

With the rapid

upswing in cottage

construction, there

was of course an

increased demand

for land. Such a

demand presented

landowners with an

opportunity to do

some good "Yankee"

trading with city

folk, who were at

first mostly Bos-

tonians. In 1867,

Alpheus Hardy had

paid Stephen Hig-

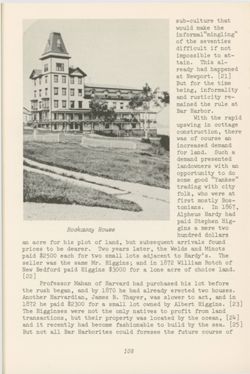

Rockaway House

gins a mere two

hundred dollars

an acre for his plot of land, but subsequent arrivals found

prices to be dearer. Two years later, the Welds and Minots

paid $2500 each for two small lots adjacent to Hardy's. The

seller was the same Mr. Higgins; and in 1872 William Rotch of

New Bedford paid Higgins $3000 for a lone acre of choice land.

[22]

Professor Mahan of Harvard had purchased his lot before

the rush began, and by 1870 he had already erected two houses.

Another Harvardian, James B. Thayer, was slower to act, and in

1872 he paid $2300 for a small lot owned by Albert Higgins. [23]

The Higginses were not the only natives to profit from land

transactions, but their property was located by the ocean, [24]

and it recently had become fashionable to build by the sea. [25]

But not all Bar Harborites could foresee the future course of

108

events. Some, either foolishly or naively (or both), sold

their land to non-resident speculators at prices that in a few

short years could have been multiplied many times.

Regardless from whom they bought the land, the new owners

were eager to start construction of their summer homes. Gouver-

neur Ogden and William Minot had cottages built at once, and

workmen soon built homes for Professor Thayer, Haskett Derby,

Charles H. Door (whose son would found Acadia National Park),

and Philadelphia's much-traveled Reverend DeCosta. The Hales

had three houses at Schooner Head, near the old Lynam Home-

stead where the early artists had stayed, and local carpenters

soon built a Swiss cottage in the same vicinity for Salem's

Judge Brigham. The chalet was shared by Charles Francis and

family of Boston. The Doors lived at the edge of Bar Harbor,

but most of the other cottagers lived in the village proper.

Many Bar Harborites were active in the building trades, and if

the necessary skills and supplies could not be provided locally,

assistance could be found in Ellsworth, or Bucksport (located

at the mouth of the Penobscot River). [26] Shingles and other

materials were needed on an unprecedented scale, and local

production could not always keep pace.

By the end of the decade, a cottage "colony" had been es-

tablished. It was evident that this colony would consist

primarily of Bostonians, New Yorkers, and Philadelphians, with

a few representatives from Baltimore, Chicago, and the District

of Columbia. Geography and the distribution of wealth dictated

that the first named cities would dominate Bar Harbor society

as they dominated Newport's. But as the Harper's article sug-

gests, there was a considerable difference between intellectual

Bostonians, sensual New Yorkers, and (arbitrarily) aristocratic

and arrogant Philadelphians. The future history of Bar Harbor

society would be, in part, a reflection of the interplay among

these groups. But a resort is not created by resorters alone,

not even if their names are Vanderbilt, Stotesbury, Pulitzer,

and Blaine. From 1870 onward the story of Bar Harbor is the

story of a community meeting the demands of a growing number

of affluent and influential resorters, people SO unlike the

local inhabitants as to be of a different world. It is as much

a story for the sociologist as for the historian.

Bar Harbor's progress did not go unimpeded. In 1873 the

townspeople, and especially the proprietors and merchants, were

faced with a problem of almost overwhelming magnitude. For a

short time, it appeared that Bar Harbor's days as a resort

might be numbered. A rapid-fire series of disasters shocked

the community. First, the giant Atlantic House was totally

destroyed by fire. The town had taken no precautions against

109

such a hazard, and while hundreds stood helplessly by, the ho-

tel was reduced to ashes. A few guests were able to salvage

their belongings, but all else was lost. For the citizens the

fire was a traumatic experience. If the Atlantic House was

not safe from fire, neither were the other fragile structures

that lined Bar Harbor's main thoroughfares. [27]

Soon after the remains of the hotel ceased smoldering,

Bar Harbor was struck by an epidemic of typhoid fever. Eight

residents of the Bay View House were afflicted, and the hotel

was evacuated immediately. The entire village water supply

was suspect, and many resorters fled the town altogether.

Others crowded the remaining hotels. Word was flashed across

the United States that Bar Harbor, noted for its invigorating

air, was unhealthful. Conditions became more acute when an

outbreak of scarlatina was reported by the occupants of the

Rodick House. [28] Unfavorable publicity was an inevitable

result of this unhappy sequence of events, and the New York

Times warned the proprietors of the resort's "hastily built"

hotels to look after the problem of drainage if Bar Harbor

were to survive, a warning echoed by other newspapers. [29]

Fortunately the townspeople were attuned to their col-

lective plight, and no time was wasted in inactivity. The

cause of the outbreak was found to be the well at the Bay

View House. No other wells were contaminated. [30] Since

open sewers had long run past the wells of the village, the

only wonder is that such a tragedy was SO long delayed. A

remedy was sought at once. The selectmen led a movement to

replace all open sewers with cesspools, and town officials

petitioned the Maine Legislature for financial help in pro-

viding pure water for the inhabitants. [31] The Legislature

responded favorably, and in the spring of 1874 wooden flumes

were built to carry water from spring-fed Eagle Lake, two

miles distant, to Bar Harbor. [32] In June the New York

Tribune reported that Bar Harbor was safe for another sea-

son, [33] and according to a popular magazine 11 the reports

of illness are much exaggerated," probably an accurate

observation. [34]

Much energy was expended because much was at stake. The

threat the epidemic posed to the resort's very existence was

SO great that total mobilization of the populace was easy to

achieve. It was not the cottagers or the boarders who came

to the rescue of the resort, but the inhabitants themselves.

The Rodicks, the Higginses, E. G. DesIsles, and Alfred Con-

nors were the moving forces behind the creation in 1874 of

the Bar Harbor Water Company (capitalized at $50,000), the

organization that carried out the task of procuring pure

110

water for the town. [35] As heresy frequently strengthens

orthodoxy, SO did the crisis of 1873 strengthen the resolve

of Bar Harborites to persevere in their resort enterprise.

They became aware of their common destiny. Vacationers could

vacation elsewhere, but the natives could not replace the

tourist dollar. Not surprisingly then, the proprietors and

merchants were prominent in the recovery process.

Local merchants had been active long before the summer

of 1873. The arrival of an increasing number of steamers

brought unprecedented activity to the waterfront. Tobias Ro-

berts enlarged his wharf twice. Joseph Wood, a Wiscasset

native, built a wharf, and the Connors brothers, in partnership

with Jacob Suminsby, erected yet another. [36] A few years

later, at the instigation of Captain Charles Deering, the East-

ern Railroad bought the Roberts wharf which had been used as

the main steamboat landing. [37] Roberts, the Connorses, and

Suminsby also rented rowboats and canoes to tourists, [38] and

it was not long before members of Maine's Penobscot and Passa-

maquoddy Indian tribes took advantage of their proximity to

Bar Harbor. Camping on the shore across from Bar Island, the

Indians taught rusticators the art of birch-bark canoeing,

served as guides, and ,ironically, sold trinkets to the white

man. [39]

Other businesses were growing as well, and the response

of Bar Harborites to the crisis of 1873 encouraged more re-

sorters than ever to buy land and build cottages. This in

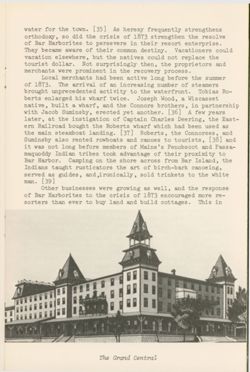

The Grand Central

turn created more economic opportunities for local merchants

and manufacturers. Boarders and cottagers alike had plenty

of money to spend. The hotels needed waitresses, maids, and

kitchen help, jobs that local women and girls could do, and

many women also did thriving laundry businesses. Young men

served as guides, drivers, rowers, and as clerks in a growing

number of stores. Others worked as gardeners on the grounds

of the hotels and cottages, while a few responsible older men

served as caretakers for one or another of the cottagers.

Farmers grew fruits and vegetables for the hotel dining rooms,

and of course a steady supply of blueberries had to be main-

tained. The business of Bar Harbor was business, one busi-

ness-tourism. [40]

According to the Maine Register, Bar Harbor had fourteen

retail business establishments in 1870, seventeen in 1875, and

more than twenty by 1880. Three merchants who early recog-

nized Bar Harbor's potential were non-residents. Richmond H.

Kittredge, from Trenton, opened a grocery store in 1870, and

within a short time he had competition from H. C. Sproul of

Bucksport; another Sproul, Robert, opened the resort's first

restaurant across from the Rodick House, but most resorters

continued to eat at one or another of the hotels and boarding

houses. Then the local citizens got involved. In 1875 John

Harden established a livery stable, to cater to the hotel

trade, and by the end of the decade, four others had been

built in competition. [41] The Rodicks not only enlarged

their hotel, but also built salt-water baths, an innovation

that attested to the changing tastes of their clientele. By

1880, Bar Harbor could claim the presence of a seasonal ar-

chitect, a dentist, a physician, and a photographer. [42]

The resort was beginning to assume an air of sophistication,

and as more and more buildings were erected, Bar Harbor began

to look different - less crude, less run-down. The cultivated

tastes of the newer cottagers soon were reflected in the con-

struction of more palatial summer homes.

Thanks to Tobias Roberts and others, Bar Harbor also pro-

cured its own telegraph office. In 1870 a telegraph line was

completed between Ellsworth and Southwest Harbor, and on Feb-

ruary 3, 1871, the State Legislature granted permission to the

Robertses to connect with this line. [43] Soon the Bar Harbor

and Mount Desert Telegraph Company was in full operation. [44]

Would-be resorters could wire ahead for reservations if they

SO desired, and boarders and cottagers could readily communi-

cate with friends, relatives, and business associates back

home if the occasion arose. Moreover, proprietors and mer-

chants could telegraph orders to wholesalers in Portland and

112

Boston, and have their goods within the week via one of the

steamers. [45]

Resorters, whether cottagers or boarders, still continued

to do those things people traditionally came to Bar Harbor to

do. City-dwellers, avoiding the heat and dust of the metro-

polis, often arrived 11 in a state of mind for which there

is no cure save our beloved Bar Harbor. [46] They came to

walk (and hike), to talk (and gossip), to canoe, to picnic at

the "ovens" or elsewhere, and just to enjoy the out-of-doors.

Fishing remained popular, but swimming was still ruled out

because of the frigid temperature of the water. [47] Dancing

was never popular at Bar Harbor, but dances were, and dances

were Bar Harbor's first truly public entertainment. Dances

were a gathering place for the young, and Bar Harbor was,

above all else, a haven for the young during its formative

years. The ballroom of the Rodick House popularly was known

as the "fish pond," and there young ladies "fished" for male

companions. There were too many women and too few men at Bar

Harbor, making the female of the species by necessity the

predator. Apparently the art of flirtation was well taught

by Bar Harbor's widows and young-at-heart matrons, for the

resort soon held an unsurpassed reputation as America's fore-

most site for "love making" whatever that meant in the 1870s

and 1880s. Chaperones worried less and enjoyed life more at

Bar Harbor than in the self-conscious society of Newport and

other watering places. [48]

Chaperones were considered superfluous when young couples

canoed on the choppy waters of Frenchman's Bay, and there

seemed to be no danger in permitting maidens to attend the

afternoon teas on Bar Island, for the atmosphere was always

"proper." Buckboard rides on wilderness roads might have

posed a threat, had not all local buckboards been three-

seaters, a feature that enabled younger brothers and sisters

to go along for the ride. Lawn tennis was in vogue at Bar

Harbor, but the resort's tennis players apparently were not

fashionable. According to one protesting observer, "Mount

Desert is anything but fashionable. It is the last place in

the world to get an opportunity to show good clothes," [49]

this after he had witnessed a tennis match. Still by the

decade's end, Mrs. Burton Harrison could refer to Bar Harbor

as a smart, modern watering place, which was (fortunately she

said) far from being too sophisticated. [50] Others still

considered Bar Harbor to be crude, but sophistication clearly

was emerging and the seventies brought changes that augured

ill for the old order of the rusticators.

The growth of the cottage colony was one such change, and

113

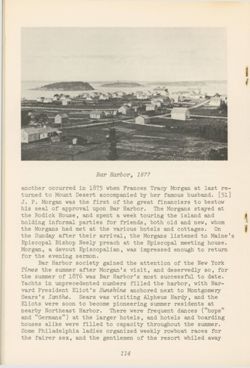

Bar Harbor, 1877

another occurred in 1875 when Frances Tracy Morgan at last re-

turned to Mount Desert accompanied by her famous husband. [51]

J. P. Morgan was the first of the great financiers to bestow

his seal of approval upon Bar Harbor. The Morgans stayed at

the Rodick House, and spent a week touring the island and

holding informal parties for friends, both old and new, whom

the Morgans had met at the various hotels and cottages. On

the Sunday after their arrival, the Morgans listened to Maine's

Episcopal Bishop Neely preach at the Episcopal meeting house.

Morgan, a devout Episcopalian, was impressed enough to return

for the evening sermon.

Bar Harbor society gained the attention of the New York

Times the summer after Morgan's visit, and deservedly so, for

the summer of 1876 was Bar Harbor's most successful to date.

Yachts in unprecedented numbers filled the harbor, with Har-

vard President Eliot's Sunshine anchored next to Montgomery

Sears's Ianthe. Sears was visiting Alpheus Hardy, and the

Eliots were soon to become pioneering summer residents at

nearby Northeast Harbor. There were frequent dances ("hops"

and "Germans") at the larger hotels, and hotels and boarding

houses alike were filled to capacity throughout the summer.

Some Philadelphia ladies organized weekly rowboat races for

the fairer sex, and the gentlemen of the resort whiled away

114

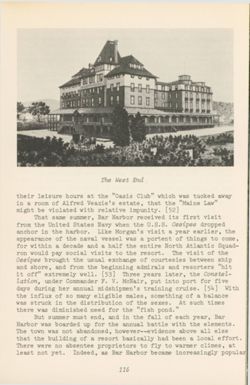

The West End

their leisure hours at the "Oasis Club" which was tucked away

in a room of Alfred Veazie's estate, that the "Maine Law"

might be violated with relative impunity. [52]

That same summer, Bar Harbor received its first visit

from the United States Navy when the U.S.S. Ossipee dropped

anchor in the harbor. Like Morgan's visit a year earlier, the

appearance of the naval vessel was a portent of things to come,

for within a decade and a half the entire North Atlantic Squad-

ron would pay social visits to the resort. The visit of the

Ossipee brought the usual exchange of courtesies between ship

and shore, and from the beginning admirals and resorters "hit

it off" extremely well. [53] Three years later, the Constel-

lation, under Commander F. V. McNair, put into port for five

days during her annual midshipmen's training cruise. [54] With

the influx of SO many eligible males, something of a balance

was struck in the distribution of the sexes. At such times

there was diminished need for the "fish pond."

But summer must end, and in the fall of each year, Bar

Harbor was boarded up for the annual battle with the elements.

The town was not abandoned, however--evidence above all else

that the building of a resort basically had been a local effort.

There were no absentee proprietors to fly to warmer climes, at

least not yet. Indeed, as Bar Harbor became increasingly popular

115

as a summer resort, the year-round population grew ever larger.

Throughout the 1870s the movement of Edenites to Bar Harbor

continued. The number of students attending the schools at

Bar Harbor increased from 75 in 1875 to 187 five years later.

In the other fourteen school districts the number of students

declined proportionately. [55]

As the town grew larger, SO did the problems facing lo-

cal government. The selectmen were confronted with new prob-

lems of law enforcement. The old system of a volunteer

constabulary might suffice in the winter, but during the bust-

ling summer months it was grossly inadequate. Professionals

were needed, and in 1877 a town police department was organized,

with anywhere from one to twenty-five policemen on duty accord-

ing to the time of year.

Public health was also a problem of increasing complexity.

The rapid and expansive construction of hotels, cottages, stores,

and ordinary dwellings created a serious sewerage problem point-

ed up most dramatically by the crisis of 1873. Lack of a com-

prehensive sewerage disposal system was to be a nuisance for

some time to come, for cesspools were at best a temporary ex-

pedient. But as noted before the town now possessed an

abundant supply of pure water, and in 1879 a Board of Health

was organized to deal with sanitation problems. Governmental

services were thus being expanded to cope with the many prob-

lems created by the resort's prodigious growth. [56]

Education and highways continued to be priority items in

the town budget. Edenites spent 20 per cent of their tax

dollar on education during the seventies, and Eden's schools,

as a group, now were considered the best in the county. [57]

An even greater portion of tax revenue was allocated for road

and bridge construction and repair. [58] Such continuous

attention to the public thoroughfares was essential if the

reputation of the resort was to grow. The physical appearance

of Bar Harbor became increasingly important after 1880 as the

wealthy began to arrive in large numbers. But even in the

seventies local merchants were beginning to recognize the

necessity of catering to tastes that were more demanding than

those of the early artists and intellectuals.

It was during the seventies also that some cottagers and

a few perennial boarders began to intrude into Bar Harbor's

spiritual and intellectual life. Resorters thus were moving

into spheres of activity that long had been the preserve of

the year-round inhabitants. One example of this new activism

was the movement of the Episcopalians from the Union Meeting

House to their own quarters. Exhorted to action by Maine's

socially prominent Episcopal Bishop Henry Adams Neely,

116

several cottagers and boarders contributed money to purchase

a site for a proposed new church. In the meantime, temporary

facilities were found, and the first Episcopal services were

held by Bishop Neely (himself a frequent visitor at Bar Har-

bor) in 1867. Twelve years later, Bar Harbor's first Episco-

pal Church edifice was consecrated. The exodus from the

"white church" had begun. [59]

The summer residents also contributed to Bar Harbor's

cultural enrichment by planning a public library. During the

summer of 1875, and in the face of local apathy, a group of

interested persons gathered at the Minot Cottage to discuss

the library project. Several cottagers were willing to con-

tribute books and money, and one concerned local resident, Mrs.

Endora Salisbury, offered a room of her house to be used as a

reading room. So the project was begun, and with considerable

success. Within a short time the popularity of the reading

room dictated that roomier quarters be found, and a committee

was formed to purchase a building site, preferably near the

center of town. Professor James B. Thayer was elected chairman

of the library committee, and additional funds were collected

for the purchase of more books. The Town of Eden, in a brief

spasm of short-sightedness, refused to contribute any money to

the project. Through the efforts of interested cottagers, how-

ever, the library was perpetuated, and within a few years, the

annual circulation of books exceeded 5,000, two-thirds of which

were borrowed by year-round residents. [60]

Subtly but steadily, cottagers were becoming involved in

the day to day life of the community. This trend continued,

and increasingly the cottage colony had more and more to say

about local affairs. Of course the boarders, more transient

in character than the cottagers, were less concerned with local

problems and politics, and, not being taxpayers, were less in-

fluential. Thus the decline of the boarders and the rise of

the cottagers, a development that unfolded during the 1880s,

had profound effects upon the relationship between summer and

year-round residents.

As a permanent summer colony evolved, a more servile

mentality began to develop among local inhabitants. Working

for and catering to the summer colonists rapidly came to be

the prime function of Bar Harborites. The resort trades were

the new "way of life" at Bar Harbor, and as older occupations

faded from the picture, dependency upon the boarders and

cottagers became complete. With the 1880s came the birth of

the Bar Harbor of popular legend.

117

NOTES

1. Bar Harbor Municipal Offices, Town Records: Valuation,

1870. Hereafter referred to by short title giving con-

tent and date; N. K. Sawyer, Mount Desert Island and the

Cranberry Isles (Ellsworth: By the Compiler, 1871), p. 41.

2. Town Records: Contracts and Bills of Sale, 1870-79.

3. George Adams, comp., Maine Register and Business Direc-

tory, 1855 (Title and place of publication vary, 1855),

pp. 149-50. Hereafter referred to as Maine Register,

followed by the year of publication.

4. Town Records: Contracts and Bills of Sale, 1877; Albert H.

Davis, History of Ellsworth, Maine (Lewiston: Lewiston

Journal Printshop, 1927), p. 185.

5. Town Records: Contracts and Bills of Sale, 1879.

6. These dates have been determined by using the Maine Regis-

ter and the Bar Harbor Town Records. The author believes

these dates to be the most precise that it is possible to

obtain.

7. Maine Register, 1880, p. 345.

8. The best account of the qualities of Bar Harbor's hotels

is in Henry Walton Swift's Mount Desert in 1873, Portrayed

in Crayon and Quill (Boston: J. R. Osgood and Co., 1873).

Hereafter referred to as Mount Desert in 1873. Also see

George Ward Nichols, "Mount Desert," Harper's, August,

1872, pp. 321-40. More favorably disposed to the hotels

is Mrs. Burton Harrison, Golden Rod, An Idylz of Mount

Desert (New York: Harper and Bros., 1879). Hereafter

referred to as Golden Rod.

9. Nichols, "Mount Desert," p. 327.

10. Sawyer, Mount Desert Island and the Cranberry Isles, pp.

60-64; Samuel Adams Drake, Nooks and Corners of the New

England Coast (New York: Harper and Bros., 1875), p. 39.

J.H. Douglass and Edward DesIsles pooled their resources

to buy a $485.00 piano for the Atlantic's Music Room

(Town Records: Contracts and Bills of Sale, 1874).

11. Swift, Mount Desert in 1873, pp. 1-3, 8.

12. Boston Daily Advertiser, August 8, 1873; Clara Barnes

Martin, Guide Book for Mount Desert Island, Maine (Port-

land: Loring, Short, and Harmon, 1874), p. 23. Hereafter

referred to as Guide Book.

13. See n. 12.

14.

Benjamin F. DeCosta, Rambles in Mount Desert: With Sket-

ches of Travel on the New England Coast, from the Isle

of Shoals to Grand Manan (New York: A.D.F. Randolph and

Co., 1871).

118

15. Ezra Dodge, History of Mount Desert (Ellsworth: N.K.

Sawyer, 1871).

16. For an account of the development of railroads in Maine

see George Pierce Baker, The Formation of the New England

Railroad Systems (Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

1937), chs., VII, IX. This may be supplemented with

newspaper advertisements in the Eastern Argus and the

Bangor Whig and Courier.

17.

The best account of the development of Maine steamboating

is F.B.C. Bradlee, Some Account of Steam Navigation in

New England Salem: The Essex Institute, 1929). Also see

Martin, Guide Book, 1874, p. 12. The newspaper advertise-

ments mentioned in the previous footnote also deal with

steamboats.

18

Town Records: Valuation, 1870-79.

19. Nichols, "Mount Desert, p. 328; John Arbuckle, "A Temper-

ate Experience on Mount Desert, Lippincott's, August,

1874, pp. 250-53; New York Times, September 5, 1880, p. 10.

20. See such secondary sources as the Dictionary of American

Biography and Who Was Who.

21. Dixon Wecter, The Saga of American Society (New York:

Scribner's Sons, 1937), p. 456.

22. Town Records: Contracts and Bills of Sale, 1867,1869 and

1872.

23. Ibid., 1872.

24. Albert L. Higgins, Notes from the Early History of Mount

Desert Island (Bar Harbor: By the Author, 1929), n.p.,

see map.

25. Roderick Nash, wilderness and the American Mind (New York:

Yale University Press, 1967), pp. 57-83, 101-07.

26. Ellsworth American, December 30, 1869; Town Records: Val-

uation, 1869-72 and Contracts and Bills of Sale, 1879;

also see the various guidebooks and early maps of the is-

land.

27. Swift, Mount Desert in 1873, pp. 12-13.

28. Ibid., p. 13.

29. New York Times, June 28, 1874, p. 6; Richard W. Hale, Jr.

The Story of Bar Harbor (New York: Ives Washburn, 1949),

p. 142-47. Hereafter referred to as Bar Harbor.

30. Dr. William James Morton, "Mount Desert and Typhoid Fever,

During the Summer of 1873," Boston Medical and Surgical

Journal, Vol. 89. Found in Hale, Bar Harbor, p. 145.

31. Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of

Maine 1874 (Augusta: Sprague, Owen and Nash, 1874), p. 192.

32. Martin, Guide Book, 1874, advertisements; Rodick House

pamphlet, dated 1875 and located at Bar Harbor Historical

Society.

119

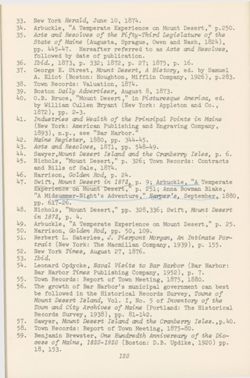

33. New York Herald, June 10, 1874.

34. Arbuckle, "A Temperate Experience on Mount Desert," p.250.

35. Acts and Resolves of the Fifty-Third Legislature of the

State of Maine (Augusta, Sprague, Owen and Nash, 1824),

pp. 445-47. Hereafter referred to as Acts and Resolves,

followed by date of publication.

36. Ibid., 1873, p. 332; 1872, p. 27; 1875, p. 16.

37. George E. Street, Mount Desert, A History, ed. by Samuel

A. Eliot (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin Company, 1926), p. 283.

38. Town Records: Valuation, 1874.

39. Boston Daily Advertiser, August 8, 1873.

40. O.B. Bruce, "Mount Desert," in Picturesque America, ed.

by William Cullen Bryant (New York: Appleton and Co.,

1872), pp. 2-3.

41. Industries and Wealth of the Principal Points in Maine

(New York: American Publishing and Engraving Company,

1893), n.p., see "Bar Harbor."

42. Maine Register, 1880, pp. 344-45.

43. Acts and Resolves, 1871, pp. 548-49.

44. Sawyer,Mount Desert Island and the Cranberry Isles, p. 6.

45. Nichols, "Mount Desert," p. 326; Town Records: Contracts

and Bills of Sale, 1874.

46. Harrison, Golden Rod, p. 24.

47. Swift, Mount Desert in 1873, p. 9; Arbuckle, "A Temperate

Experience on Mount Desert, 99 p. 251; Anna Bowman Blake,

"A Midsummer-Night's Adventure," Harper's, September, 1880,

pp. 617-26.

48. Nichols, "Mount Desert," pp. 328,336; Swift, Mount Desert

in 1873, p. 4.

49. Arbuckle, "A Temperate Experience on Mount Desert," p. 25.

50. Harrison, Golden Rod, pp. 50, 109.

51. Herbert L. Saterlee, J. Pierpont Morgan, An Intimate Por-

trait (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939), p. 155.

52. New York Times, August 27, 1876.

53. Ibid.

54. Leonard Opdycke, Naval Visits to Bar Harbor (Bar Harbor:

Bar Harbor Times Publishing Company, 1952), p. 7.

55. Town Records: Report of Town Meeting, 1875, 1880.

56. The growth of Bar Harbor's municipal government can best

be followed in the Historical Records Survey, Towns of

Mount Desert Island, Vol. I, No. 5 of Inventory of the

Town and City Archives of Maine (Portland: The Historical

Records Survey, 1938), pp. 81-142.

57. Sawyer, Mount Desert Island and the Cranberry Isles. p. 40.

58. Town Records: Report of Town Meeting, 1875-80.

59. Benjamin Brewster, One Hundredth Anniversary of the Dio-

cese of Maine, 1820-1920 (Boston: D.B. Updike, 1920) pp.

18, 153.

120

60. Bar Harbor village Library, 1875-1905 (Bar Harbor: By the

Library, 1906). This is a brief sketch of the library's

growth and development and lists those involved in forming

the library, most of whom are non-residents.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1. Agamont House. Built in 1855 by Tobias Roberts,

the Agamont was Bar Harbor's first hotel.

Figure 2. Green Mountain House. The original was erected on

this site in 1861 by Bar Harborite Daniel Brewer.

Figure 3. Rodick House. Begun in 1866 by David Rodick and

sons, this hotel became Bar Harbor's largest, and

during the 1870s, the most popular.

Figure 4.

Rockaway House. Tobias Roberts's second hotel,

built about fifteen years after the Agamont, on a

more grandiose scale.

Figure 5.

The Grand Central. Built in 1876, it was Bar

Harbor's second largest hotel.

Figure 6. Bar Harbor, 1877. The Rodick and Grand Central are

at the right-center of the picture. Most summer

cottages remain hidden behind the hotels, or are

beyond view.

Figure 7. The West End. The last hotel built during the

seventies, and the first built by a non-resident

(O.M. Shaw), it was Bar Harbor's third largest.

Agamont House, reproduced on page 101,

appears through the courtesy of Mr. Bernard

Hawkes. All other illustrations are from the

Maine Historical Society Collections.

Richard A. Savage, a native of Bar Harbor, received his B.A.

from Harvard and M.A. from the University of Maine. Mr. Savage

teaches history at Leicester Junior College in Massachusetts.

121

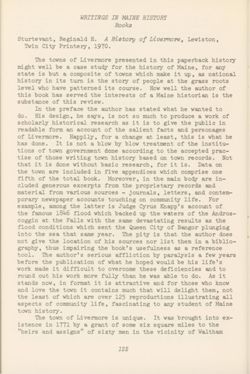

WRITINGS IN MAINE HISTORY

Books

Sturtevant, Reginald H. A History of Livermore, Lewiston,

Twin City Printery, 1970.

The towns of Livermore presented in this paperback history

might well be a case study for the history of Maine, for any

state is but a composite of towns which make it up, as national

history in its turn is the story of people at the grass roots

level who have patterned its course. How well the author of

this book has served the interests of a Maine historian is the

substance of this review.

In the preface the author has stated what he wanted to

do. His design, he says, is not so much to produce a work of

scholarly historical research as it is to give the public in

readable form an account of the salient facts and personages

of Livermore. Happily, for a change at least, this is what he

has done. It is not a blow by blow treatment of the institu-

tions of town government done according to the accepted prac-

tise of those writing town history based on town records. Not

that it is done without basic research, for it is. Data on

the town are included in five appendices which comprise one

fifth of the total book. Moreover, in the main body are in-

cluded generous excerpts from the proprietary records and

material from various sources - journals, letters, and contem-

porary newspaper accounts touching on community life. For

example, among the latter is Judge Cyrus Knapp's account of

the famous 1846 flood which backed up the waters of the Andros-

coggin at the Falls with the same devastating results as the

flood conditions which sent the Queen City of Bangor plunging

into the sea that same year. The pity is that the author does

not give the location of his sources nor list them in a biblio-

graphy, thus impairing the book's usefulness as a reference

tool. The author's serious affliction by paralysis a few years

before the publication of what he hoped would be his life's

work made it difficult to overcome these deficiencies and to

round out his work more fully than he was able to do. As it

stands now, in format it is attractive and for those who know

and love the town it contains much that will delight them, not

the least of which are over 125 reproductions illustrating all

aspects of community life, fascinating to any student of Maine

town history.

The town of Livermore is unique. It was brought into ex-

istence in 1771 by a grant of some six square miles to the

"heirs and assigns" of sixty men in the vicinity of Waltham

122

for services rendered in 1710 in reducing Port Royal in Nova

Scotia in Queen Anne's War. The grant was located in what is

now Androscoggin county, on both sides of what was then a

magnificently clean river. Ports nearest to it were Portland

and Hallowell both of which later furnished a useful outlet

for surplus food and lumber products, and as it turned out, a

way of escape from the hard chores of the farm when younger

men sought a more adventurous life, either to follow the sea

or seek greener pastures in the west.

Dominating the early history of the town to his death was

the leader of the surveying expedition in 1773 after the grant

was made, Lieut. Elijah Livermore, later known as the Deacon,

for whom the town was named. A leader in all aspects of the

early settlement he became one of the all-time wealthy men.

He built the first saw and grist mill. As a proprietor he

controlled the sale of lots and when one was sold for taxes

he was smart enough to pick it up. A spacious frame house

with two chimneys had as adjunct four sheds and four barns to

house some fifty head of cattle and other live stock, SO re-

ported the Rev. Paul Coffin when he paused on a missionary

tour. In fact, to overcome the Deacon's objections was one

of the hurdles young Dr. Cyrus Hamlin had to make when he

petitioned the voters to settle as their practitioner in

1793. Perhaps the Deacon took a more than critical look,

since the chances were good that he would have him for a son-

in-law. And he did, with interesting results. Choosing for

a farm homestead a lofty site in East Livermore, he built a

home which some fifteen years later was bought by Israel

Washburn, Sr. after Hamlin had moved his young family to

Paris, Maine, where his second son, Hannibal, was born.

Elijah, named for his grandfather, we learn from another

source, inherited the Deacon's papers which, if located,

would contain a gold mine of information for a future histor-

ian of the town. As for Washburn, he in his turn married

Martha Benjamin to become the parents of the fabled seven

sons who distinguished themselves in four states of the union,

returning each year to their ancestral home which became the

Norlands.

Possibly a more selective process than that found in

other Maine towns was used in choosing those who would live

and die in Livermore. Good influences were surely at work,

but living neighbor to others in a small Maine town was often

something of a strain. Everything in their way of life

brought out individualism. Disagreements were manifest in

the trivia of town meeting, in the practise of barter which

after all was SO much horse trading, and in the custom of the

123

church to hold the individual accountable for his moral be-

havior. Yet in surviving frictions of this nature, true

nobility of character could be developed.

As a geographical unit the town went through the usual

metamorphosis. Incorporated in 1795 and well situated it

quickly attracted settlers. By 1820 the population had grown

from 400 to 2174 and settlements spread to Millsites, Corners,

Neighborhoods, and Villages, decentralizing a town that was

already subdivided into school and highway districts. Three

ferries knit the two sides of the river together. Not until

a branch railroad was built with its depot in East Livermore

was a bridge built across the river. By that time, East Liver-

more, which comprised a fourth of the original grant, was set

off in 1843 as a separate town, known today as Livermore Falls.

Livermore then, in this book, is not one town but two.

One belongs to Maine's past, the other to its present and fu-

ture. Livermore on the west bank of the river is similar in

its history and economy to a number of small agricultural

towns within a radius of thirty miles, whose dwindling popula-

tion after 1850 is marked by empty cellar holes, scraggly

orchards, and untilled fields, deserted by young men who pre-

ferred a new life in the mills of southern New England or in

the mining and agricultural areas of the west to picking up

rocks on a not too productive Maine farm. Hundreds left from

this area. Of 475 Maine natives whose achievements in other

states warranted their inclusion in the Dictionary of American

Biography, sixty originated in this little pocket of south-

western Maine, in what are now such little known towns as

Wayne, Sumner, Hebron, Buckfield, Hartford, Fayette, Chester-

ville and Canton, and from four larger towns whose economy

survived as did Livermore at the Falls, Farmington, Wilton,

Jay and Turner.

Farming as a way of life had also produced crafts such

as the making of wool and linen cloth, the tanning of leather

for shoes, and the making of furniture which would develop

into carriage and sleigh manufacture. At East Livermore, or

the Falls, this type of industry developed and as time passed

and a changing mill economy took place in the state, as pulp

and paper replaced in part the production of long lumber, the

industry at the Falls changed to meet the changing times. In

both towns specialized agriculture is still carried on.

A good deal of human interest is buried in the pages of

this book, more perhaps than if the author had followed con-

ventional lines. Now, with two earlier brief accounts done

in 1874 and 1928, the time is ripe for a full scale history

of the town.

Elizabeth Ring

Maine Historical Society

Leavitt, John F. Wake of the Coasters, Middletown, Connecti-

cut, published for the Marine Historical Association by

Wesleyan University Press, 1970.

Coasting schooners were perhaps more important to Maine

than to other parts of the Atlantic seaboard, because the

schooner was better able and longer able to meet Maine's prime

transportation need: the export of raw materials. It is also

true that since land transportation along the coast of Maine

was (and is) more difficult that along other sections of the

coast, the coasters were more important to Maine's coastal

towns than to other towns in terms of basic communication with

the outside world.

Maine men early recognized that their unique coast could

produce large quantities of lumber, stone, lime, and ice badly

needed by their countrymen to the wouthwest. All that was

needed to turn these resources into dollars was a great deal

of hard work -- and a fleet of burdensome vessels to carry the

stuff. It is of this fleet and the men who manned it that

John Leavitt writes.

Wake of the Coasters is a book that would be welcome,

frankly, even if it were badly done. All too little has been

written about the coasting schooners. By contrast, there are

shelves of books on the supposedly more glamorous clippers

and whalers.

Happily, Wake of the Coasters is doubly welcome because

it is an exceedingly well done book. John Leavitt is a care-

ful researcher and a good writer. And, best of all, he sailed

in some of the vessels of which he writes.

Because of his first-hand experience and his natural fac-

ility with the language, John Leavitt takes the reader right

aboard these homespun schooners, makes him acquainted with

captain and crew, passes him a hot mug-up off the crackling

wood stove, and then, if there's "a good chance along," takes

him sailing a cargo among the islands and peninsulas of the

coast of Maine. He tells what it was really like to do it;

what the vessels were like, what the men were like, how the

sails were handled, how the anchors were handled, how the

cargo was handled.

And John Leavitt has liberally illustrated his book, not

only with a rare collection of photographs, but also with his

fine marine drawings. The caption under one of them is, "My

berth in the Alice S. Wentworth's after house. A snug place

to be on a cold winter night." It's a rare author of mari-

time history who was there, can write about it, and can draw it.

Nor is John Leavitt to be left behind when the pipe smoke

starts to curl and there are yarns to be spun. His tale of

125

Captain Parker J. Hall, the legendary character who sailed

coasting schooners for years with only a cat for crew, should

be read by anyone interested in the sea. No mere foible,

Hall's lonely cargo-carrying resulted from his being jumped

for freight money by his crew of three men early in his career.

Hall kept his money, but decided he'd rather cope with wind

and wave shorthanded than pit himself against perverse human

nature.

The lessons of sail come through strongly in this book.

The men who conscientiously devoted themselves to their vessels,

who spent a fine afternoon making a spare canvas hatch cover

against the surely coming storm, these men kept their vessels

safe and usually made money. Of course luck always plays its

part at sea, but the best seamen seemed to have a way of avoid-

ing bad luck. Another lesson that comes through strongly in

John Leavitt's writing is the sense of satisfaction of moving

a heavy cargo to its destination with nothing but the brains

and backs and hands of a few men.

This book results from a happy combination of efforts be-

tween the Mystic Seaport and Wesleyan University Press. It is

the second volume in the American Maritime Library. The first

was Glory of the Seas, a book about the famous Donald McKay

clipper, by Michael Jay Mjelde; the third volume is Ben-Ezra

Stiles Ely's There ,She Blows: A Narrative of a Whaling Voyage

in the Indian and South Atlantic Oceans, edited by Curtis Dahl.

The three volumes have set a high standard in book publishing.

Wake of the Coasters is a particularly fine example of

the art of book making. The book is well researched, well

written, well edited, and well illustrated. It has been sen-

sitively designed and well printed and bound. The publisher

has advertised it thoroughly to the maritime and historical

communities. We have here a fine team effort from which the

reader can gain much.

The only lack in this book is an index, an oversight

which hopefully will be corrected in the future printings

this book deserves and will doubtless attain.

Roger C. Taylor

International Marine Publishing

Company

126

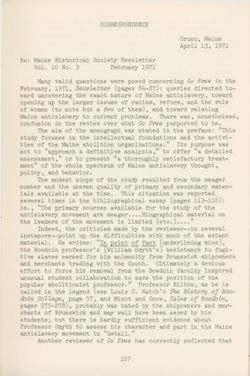

CORRESPONDENCE

Orono, Maine

April 13, 1971

Re: Maine Historical Society Newsletter

Vol. 10 No. 3

February 1971

Many valid questions were posed concerning Go Free in the

February, 1971, Newsletter (pages 84-87) : queries directed to-

ward uncovering the exact nature of Maine antislavery, toward

opening up the larger issues of racism, reform, and the role

of women (to note but a few of them), and toward relating

Maine antislavery to current problems. There was, nonetheless,

confusion in the review over what Go Free purported to be.

The aim of the monograph was stated in the preface: "This

study focuses on the intellectual foundations and the activi-

ties of the Maine abolition organizations." Its purpose was

not to "approach a definitive analysis," to offer "a detailed

assessment," or to present "a thoroughly satisfactory treat-

ment" of the whole spectrum of Maine antislavery thought,

policy, and behavior.

The modest scope of the study resulted from the meager

number and the uneven quality of primary and secondary mater-

ials available at the time. This situation was reported

several times in the bibliographical essay (pages 113-116):

ie. "The primary sources available for the study of the

antislavery movement are meager

Biographical material on

the leaders of the movement is limited (etc.

99

Indeed, the criticism made by the reviewer--in several

instances--point up the difficulties with much of the extant

material. He writes: "In point of fact [underlining mine],

the Bowdoin professor's [William Smyth's] assistance to fugi-

tive slaves earned for him animosity from Brunswick shipowners

and merchants trading with the South. Ultimately a devious

effort to force his removal from the Bowdoin faculty inspired

unusual student collaboration to save the position of the

popular abolitionist professor. " Professor Blithe, as he is

called in the legend (see Louis C. Hatch's The History of Bow-

doin College, page 57, and Minot and Snow, Tales of Bowdoin,

pages 275-278), probably was hated by the shipowners and mer-

chants of Brunswick and may well have been saved by his

students; but there is hardly sufficient evidence about

Professor Smyth to assess his character and part in the Maine

antislavery movement in "detail."

Another reviewer of Go Free has correctly reflected that

127

"Go Free is intended as descriptive history and, hence, con-

tains a minimum of analysis. This is perhaps unfortunate, for

a number of nagging questions occur which the book doesn't

answer." This comment is accurate. I regret the scarcity and

unevenness of the materials which I had to work with; I there-

fore await with anticipation the finding of additional primary

and secondary sources which will allow answers to these "nag-

ging questions" to be attempted.

Edward O. Schriver

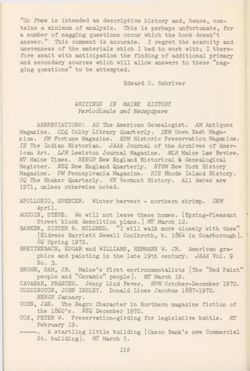

WRITINGS IN MAINE HISTORY

Periodicals and Newspapers

ABBREVIATIONS: AG The American Genealogist. AM Antiques

Magazine. CLQ Colby Library Quarterly. DEM Down East Maga-

zine. FM Fortune Magazine. HPM Historic Preservation Magazine

IH The Indian Historian. JAAA Journal of the Archives of Amer-

ican Art. LJM Lewiston Journal Magazine. MLR Maine Law Review.

MT Maine Times. NEHGR New England Historical & Genealogical

Register. NEQ New England Quarterly. NYHM New York History

Magazine. PM Pennsylvania Magazine. RIH Rhode Island History.

SQ The Shaker Quarterly. VH Vermont History. All dates are

1971, unless otherwise noted.

APOLLONIO, SPENCER. Winter harvest - northern shrimp. DEM

April.

AUCOIN, STEVE. We will not leave these homes. [Spring-Pleasant

Street block demolition plans. ] MT March 12.

BARKER, SISTER R. MILDRED. "I will walk more closely with thee"

[Eldress Harriett Newell Coolbroth, b. 1864 in Scarborough].

SQ Spring 1970.

BREITENBACH, EDGAR and WILLIAMS, HERMANN W. JR. American gra-

phics and painting in the late 19th century. JAAA Vol. 9

No. 3.

BROWN, SAM, JR. Maine's first environmentalists [The "Red Paint"

people and "Ceramic" people]. MT March 19.

CAVANAH, FRANCES. Jenny Lind Fever. HPM October-December 1970.

CODDINGTON, JOHN INSLEY. Donald Lines Jacobus 1887-1970.

NEHGR January.

COHN, JAN. The Negro Character in Northern magazine fiction of

the 1860's. NEQ December 1970.

cox, PETER W. Preservation-girding for legislative battle. MT

February 19.

A startling little building [Casco Bank's new Commercial

St. building]. MT March 5.

128

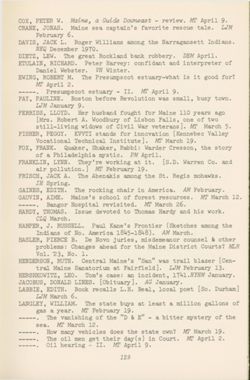

COX, PETER W. Maine, a Guide Downeast - review. MT April 9.

CRANE, JONAS. Maine sea captain's favorite rescue.tale LJM

February 6.

DAVIS, JACK L. Roger Williams among the Narragansett Indians.

NEQ December 1970.

DIETZ, LEW. The great Rockland bank robbery. DEM April.

ETULAIN, RICHARD. Peter Harvey: confidant and interpreter of

Daniel Webster. VH Winter.

EWING, ROBERT M. The Presumpscot estuary-what is it good for?

MT April 2.

Presumpscot estuary - II. MT April 9.

FAY, PAULINE. Boston before Revolution was small, busy town.

LJM January 9.

FERRISS, LLOYD. Her husband fought for Maine 110 years ago

[Mrs. Robert A. Woodbury of Lisbon Falls, one of two

still-living widows of Civil War veterans ]. MT March 5.

FISHER, PEGGY. KVVTI stands for innovation [Kennebec Valley

Vocational Technical Institute]. MT March 19.

FOX, FRANK. Quaker, Shaker, Rabbi: Warder Cresson, the story

of a Philadelphia mystic. PM April.

FRANKLIN, LYNN. They're working at it. [S.D. Warren Co. and

air pollution. ] MT February 19.

FRISCH, JACK A. The Abenakis among the St. Regis mohawks.

IH Spring.

GAINES, EDITH. The rocking chair in America. AM February.

GAUVIN, AIME. Maine's school of forest resources. MT March 12.

Bangor Hospital revisited. MT March 26.

HARDY, THOMAS. Issue devoted to Thomas Hardy and his work.

CLQ March.

HARPER, J. RUSSELL. Paul Kane's Frontier (Sketches among the

Indians of No. America 1845-1848). AM March.

HASLER, PIERCE B. De Novo juries, misdemeanor counsel & other

problems: Changes ahead for the Maine District Courts? MLR

Vol. 23, No. 1.

HENDERSON, RUTH. Central Maine's "San" was trail blazer [Cen-

tral Maine Sanatorium at Fairfield]. LJM February 13.

HERSHKOWITZ, LEO. Tom's case: an incident, 1741.NYHM January.

JACOBUS, DONALD LINES. [Obituary]. AG January.

LABBIE, EDITH. Book recalls L.H. Beal, local poet [So. Durham]

LJM March 6.

LANGLEY, WILLIAM. The state buys at least a million gallons of

gas a year. MT February 19.

The vanishing of the "D & E" - a bitter mystery of the

sea. MT March 12.

How many vehicles does the state own? MT March 19.

The oil men get their day (s) in Court. MT April 2.

Oil hearing - II. MT April 9.

129

LEANE, JACK. Maine sea monster was 9 day wonder. LJM February

6.

Maine's most fabulous salesman. [David Ingram who walked

across Maine with two companions in 1569] LJM March 6.

LEMONS, J. STANLEY and McKENNA, MICHAEL A. Re-enfranchisement

of Rhode Island Negroes. RIH February.

McDONALD, JOHN. Oil and the environment: the view from Maine.

FM April.

MERRIAM, KENDALL A. Wreck of the concrete steamer 'Polias'.

DEM April

MILLIKEN, HENRY. Maine woodsmen had favorite tall tales. LJM

January 30.

MONTGOMERY, CHARLES F. The Furniture History Society. AM April.

MYERS, JOHN L. Antislavery agents in Rhode Island 1835-1837.

RIH February.

NEWELL, ROBERT R. Murder and mutiny aboard the 'Jefferson

Borden'. DEM April.

O'TOOLE, FRANCIS J. and TUREEN, THOMAS N. State power and the