From collection COA College Publications

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Search

results in pages

Metadata

COA Magazine, v. 11 n. 2, Fall 2015

OA

THE COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Volume 11 . Number 2. . Fall 2015

ISLANDS

COA

The College of the Atlantic Magazine

Islands

Letter from the President

3

News from Campus

4

ISLANDS

8

COA's Islands

Mount Desert Rock

10

Poetry

15

COA's Islands

Great Duck Island

16

Grubbing for Petrels

22

Islands Through Time

23

In Their Own Words

Hiyasmin Saturay '15

24

Alex Borowicz '14

26

Alice Anderson '12

28

Alex Fletcher '07

29

Julia Rowe, MPhil '02

30

Barbara Meyers '89

31

The Tactile Power of Ellen Sylvarnes '83

32

Bonnie Tai's Island Return

36

New York's Forgotten Islands

38

Book Excerpt

Ocean Country

41

Alumni & Community Notes

46

Our Back Pages

The Problem of Bar Island

56

Commencement

Student Perspective

57

Herring gulls on the north face of Mount Desert Rock. Photo by Izik Dery

1

COA

The College of the Atlantic Magazine

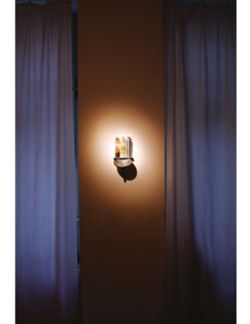

September 7, 2015, Bounty Cove, Maine

Volume 11 Number 2 Fall 2015

Midnight. We are nestled in an island cove on Penobscot Bay. Having delivered

Editorial

the magazine pieces to Rebecca Woods, who makes beautiful sense out of

Editor

Donna Gold

the disparate folders of text and photographs that form each issue, I have

Editorial Guidance

Heather Albert-Knopp '99

abandoned land for a last long voyage of the summer aboard our thirty-foot

John Anderson

Rich Borden

sloop Northern Light, which we have now sailed for almost half of its fifty years.

Darron Collins '92

But the stories I've spent a month reading, editing, rereading, these I can't

Izik Dery '17

abandon. SLEEP OUTSIDE, at least once, Teresa Bompczyk '17 urges after a

Jen Hughes

Rob Levin

summer spent on our research station at Mount Desert Rock. Her call charms,

Sean Todd

then haunts me. On our last night aboard, a light breeze whipping away the bugs,

Editorial Consultant

Bill Carpenter

I forgo our warm cabin for a cockpit bench. Not far above the horizon is the Big

Alumni Consultants

Jill Barlow-Kelley

Dianne Clendaniel

Dipper, pointing to the North Star. Scorpio, I believe, is behind me and Cassiopeia

to starboard. Our son is to starboard as well, engrossed in computer work on the

Design

bench across from me. Sleep outside-yes. But one cannot both watch the stars

Art Director

Rebecca Hope Woods

and sleep. My eyes close.

COA Administration

One a.m. Daniel's computer clicks off. "The moon's about to rise, Mom," he

President

Darron Collins '92

says as he heads into the cabin. I hear him; I want to see the moonrise-but no,

Academic Dean

Kenneth Hill

Associate Academic Deans

Catherine Clinger

I fall back asleep. Half an hour later the quarter moon is a hand's breadth above

Stephen Ressel

the eastern horizon. Waves lap against the shoreline. The tide turns, and with it

Sean Todd

our boat.

Karen Waldron

Administrative Dean

Andrew Griffiths

The depth and persistence of our students' perceptions no longer surprises

Dean of Admission

Heather Albert-Knopp 99

me, but it does still amaze me. Scientists absorb the wonder of the world

Dean of Institutional

Lynn Boulger

as if they were artists; artists understand its underpinnings as if they were

Advancement

Dean of Student Life

Sarah Luke

scientists-just look at the chemical knowledge implicit within the paintings of

Ellen Sylvarnes '83. Yes, human ecology spans the disciplines, but perhaps more

COA Board of Trustees

important, it trains the eye, encouraging, even demanding that we go deeper,

Timothy Bass

Jay McNally '84

Ronald E. Beard

Philip S.J. Moriarty

that we see and connect and then, quite possibly act, as Liz Cunningham '82 has

Leslie C. Brewer

Phyllis Anina Moriarty

done through her book Ocean Country.

Alyne Cistone

Lili Pew

We are a college on an island and a college of islands, given our two offshore

Lindsay Davies

Hamilton Robinson, Jr.

Beth Gardiner

Nadia Rosenthal

research stations. But that in no way removes us from the world. As so many

Amy Yeager Geier

Marthann Samek

of our students and alumni note throughout these pages, islands cultivate

H. Winston Holt IV

Henry L.P. Schmelzer

connection.

Philip B. Kunhardt III '77

Stephen Sullens

Anthony Mazlish

William N. Thorndike, Jr.

Sleeping outside, however, does not necessarily cultivate sleep. I shift in my

Suzanne Folds McCullagh

Cody van Heerden, MPhil 16

sleeping bag and my eyes open, once, twice, many times. I am bathed in the

Linda McGillicuddy

silence of the stars, the moon, its beauty.

Life Trustees

Trustee Emeriti

Perhaps even more than islands or the

William G. Foulke, Jr.

David Hackett Fischer

ocean, darkness connects us; we might think

Samuel M. Hamill, Jr.

George B.E. Hambleton

we are isolated, separate, alone, but night's

John N. Kelly

Elizabeth Hodder

Susan Storey Lyman

Sherry F. Huber

mystery envelopes us all.

William V.P. Newlin

Helen Porter

Yes, at least once in your life sleep

John Reeves

Cathy L. Ramsdell '78

outside, right under the stars. But don't

Henry D. Sharpe, Jr.

John Wilmerding

expect to get all that much sleep!

The faculty, students, trustees, staff, and alumni of

College of the Atlantic envision a world where people

value creativity, intellectual achievement, and diversity

of nature and human cultures. With respect and

compassion, individuals construct meaningful lives

for themselves, gain appreciation of the relationships

among all forms of life, and safeguard the heritage of

future generations.

Dam Gold

COA is published biannually for the College of the

Donna Gold, editor

Atlantic community. Please send ideas, letters, and

submissions (short stories, poetry, and revisits to

human ecology essays) to:

COA Magazine, College of the Atlantic

105 Eden Street, Bar Harbor, ME 04609

dgold@coa.edu

Cover: Looking out from a door atop Mount Desert Rock Light. Photo by Izik Dery '17.

WWW.COA.EDU

Back Cover: One a.m. A view from Great Duck Island. Photo by Nina Duggan '18.

MIX

PRINTED WITH

CERTIFIED

Paper from

responsible sources

WIND

FSC

www.fsc.org

FSC® C021556

POWER

From the President

Darron Collins '92, PhD

COA

arron Collins '92 and

daughter

piloting in Frenchman

Bay. Photo by

On a recent trip in Frenchman Bay

It was during that year of 2011

Connecting an institution of

on COA's floating classroom, the M/V

that I was introduced to the Island

higher education, a community

Osprey, COA faculty member John

Institute's Rob Snyder. We were

development non-profit like Island

Anderson told a cohort of first-year

both new to our roles. We had both

Institute, and the island communities

students, "If I had my way, I wouldn't

studied anthropology in graduate

along the coast of Maine is an

allow first-year students to come to

school. We were alike in many

innovative twist on education, on

campus by car. They'd have to get

ways, beyond both being close

development, and on applied human

dropped off with whatever gear they

to bald. Most importantly, Rob's

ecology.

can carry from Stonington, on Deer

passion for and understanding of

In this edition of COA we celebrate

Isle, board a boat, and be brought

islands-thoughtful, pragmatic, and

this young and still-developing

to the college's pier. That way they'd

respectful-aligned well with my

partnership by highlighting our

truly know where they were going

own. He understood the dynamism

community's commitment to, and

to school. They'd understand where

of island communities in Maine

exploration of, islands-both in the

we are and where they are-on an

and wasn't interested in somehow

tangible, geographic sense and in the

island-with much more clarity."

preserving islands and island

more metaphysical sense.

communities as quaint museum

I look out my office window

He wasn't kidding.

specimens. Rob also understood

toward the southern shores of

COA, how we were excellent, how

Bar Island in Frenchman Bay, the

There are obvious logistical

we were different, and how we could

expedition site of the college's first,

roadblocks to the idea, but I'd be

work together.

experimental summer in 1971. From

lying if I said I hadn't spent a few

With the help of the Partridge

that time forward, islands became an

wakeful nights trying to make it work

Foundation and many hundreds of

archetype of the college's collective

in my head. We are on an island; the

supporters throughout the state and

unconscious. Now we know they will

largest of 3,500 or so in the state.

beyond, we launched The Fund for

be an important part of our future.

That island-nature of this region and

Maine Islands, which brought COA

All the more reason to take John's

COA's specific location has played a

and the Island Institute together to

suggestion seriously.

major role in shaping who we are as

work with island communities to

an institution and who seeks to join

address their needs in the broad

Happy reading,

us. It certainly did for me as a first-

categories of food and agriculture,

year student back in 1988 and as a

energy, education, and adaptation to

first-year president in 2011.

climate change.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

3

NEWS FROM CAMPUS

JUNE

AUGUST

Naomi Klein addresses COA's 2015

Sierra Magazine rates COA as one of

graduates: "Mine is not going to

the nation's top-20 "green" schools.

be your average commencement

address, for the simple reason that

Susan and David Rockefeller present

DAWN, 6/26: PRESIDENT DARRON

College of the Atlantic is not your

Food For Thought, Food For Life, a

COLLINS '92 FINISHES HIS HIKE,

average college.

Quite remarkably,

film about those working to make

#40FOR40

you knew you wanted to go not just

positive changes to the nation's

to an excellent college, but to an

agricultural system.

excellent socially and ecologically

engaged college."

SEPTEMBER

A whopping 43% of alumni show

how much they care for this "scrappy

COA welcomes 105 students from 18

college on the beautiful coast of

countries and 22 states to the class

Maine" by donating to COA, inspiring

of 2019.

an alumna's $40,000 matching gift.

At COA everything is New! At least

"As universities and other

online. From action to whales, COA's

ALL AGES FLOCK TO FAMILY

institutions grapple with ways to

website, while still at coa.edu, is

FUN DAY AT THE PEGGY

fight climate change

the

College

of

totally changed. If nothing else, check

ROCKEFELLER FARMS

the Atlantic is nudging its students

out the home page where at College

to reach outside the school's

of the Atlantic everything is blue,

boundaries and start changing the

musical, and urgent.

real world," writes The New York Times

in "A College in Maine That Tackles

Rankings don't mean everything-

Climate Change, One Class at a Time"

but rising 17 points to #82 in the

on Page 1 of the business section.

US News & World Report rankings of

national liberal arts colleges makes

In appreciation for a $1.5 million

many of us smile. We're also noted as

endowment grant, COA's sustainable

a "best value" with small class sizes

enterprise accelerator becomes The

and a low student-faculty ratio.

RYAN HIGGINS 06

Diana Davis Spencer Hatchery.

National Wildlife Federation cites

TALKS ABOUT MAKING

CHILDREN'S BOOKS

COA as the only Maine college in

JULY

its The Campus Wild publication,

highlighting work on wildlife

Calling COA a "progressive

protection and habitat restoration in

educational experiment that

higher education.

broadens perspective," Princeton

Review ranks COA in the top 10

for its professors, food, student

OCTOBER

satisfaction, and friendliness to

LGBTQ, and top 20 for financial aid,

Eight students present scientific

beauty, and quality of life.

research at the Schoodic Research

Institute during the Acadia National

The Ethel H. Blum Gallery's summer

Park Science Symposium and

DINING OUTA

show, 2 Island Friends, 2 Points of

Down East Research and Education

BEECH HILL

View, featuring painter Clay Kanzler

Network's Convergence Conference.

and sculptor Katie Bell is reviewed as

Nina Duggan '18, Rachel Karesh '16,

magical, intriguing, spiritual.

Meghan Lyon '16, Audra McTague

'19, Ella Samuel '16, Erickson Smith

Climate Action singles out COA

'15, Bik Wheeler '09, MPhil '16, and

as one of 3 "Sustainable Colleges

Amber Wolf '17, traveled to the

Leading the Way in Sustainable

venue to present their research.

Education."

Parents, alumni, and trustees

Maine Magazine names Darron

descend on COA during Columbus

Collins '92 one of 50 "Bold

Day weekend for meetings, meet-

"A

SENSE OF PLACE

Visionaries Defining our State."

ups, and just plain fun.

AND PER AT THE

BLUM FEATURES ALUMNI

PHOTOGRAPHERS

4

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Nishanta Rajakaruna's colleague Alan Fryday

examines lichens in South Africa, where the

National Geographic-funded team will be

working come winter. Photo by Stefan Siebert.

NATIONAL GEO funds Nishi

Nishanta Rajakaruna '94, faculty member in botany,

need to thrive-particularly the rock and soil chemistry

has received a highly competitive National Geographic

upon which they grow, along with the temperature and

Society grant to conduct lichen diversity research in

rainfall.

South Africa. He'll be working with five other scholars:

"Our efforts to investigate the diversity and ecology

COA's lan Medeiros '16 and Nathaniel Pope '07, along with

of lichens-an under-studied group of organisms-in

lichenologist Alan Fryday of Michigan State, and botanist

a biodiversity hotspot like South Africa will greatly

Stefan Siebert and geologist Ricart Boneschans, both from

contribute to our understanding of lichen diversity in that

North-West University in Potchefstroom, South Africa.

country," says Nishi.

Lichens are a special kind of creature-they may

In 2014, Nishi was given a three-year visiting research

seem to be a plant, but really they're a partnership

professorship at the Faculty of Natural Sciences, North-

between fungi and algae. They're also widely used for

West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. This grant,

environmental monitoring, and South Africa has an

from National Geographic's Committee for Research and

extraordinary range of them. By studying lichens in South

Exploration, will build research capacity in South Africa,

Africa, Nishi hopes to learn what distinct species may

one of the goals of his time at the university.

BIRDERS flock to COA

Birders from around the world gathered at College of

wading bird world and to explore the cutting edge of this

the Atlantic this August during the annual meeting of the

branch of science in t-shirts and flip-flops rather than

international Waterbird Society, hosted by the college.

suits and ties."

They discussed topics that ranged from loon ecology to

The 179 attendees hailed from six countries and

the impact of offshore wind turbines on bird populations.

thirty-five states and provinces. Among them were COA

"The Waterbird Society is one of the leading

students Rachel Karesh '16 and Meaghan Lyon '16, who

international societies of scientists studying everything

presented papers, as did both John and Kate.

from sandpipers to pelicans and back again," said John

But the highlight of the meeting was getting offshore.

Anderson, faculty member in ecology and natural history,

An excursion aboard the Bar Harbor Whale Watch's

who was the conference on-site organizer along with Kate

Friendship V, expertly narrated by Zach Klyver ('90),

Shlepr '13. "This was a chance to rub shoulders and have

brought the scientists up close and personal with pelagic

a beer with some of the all-time greats of the seabird and

birds, even a shark.

COA indicates non-degree alumni by a parenthesis around their year.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

5

NEWS

ORIGIN STORY The Bar Island Swim

Left: The first Bar Island Swim participants, in 1990 (left to right): Ken Cline, Erin Marken '92, Jaime Torres '97, Kurt Jacobson '90, Wendy

Doherty '91. Right: In 2015, the 138 Bar Island Swim participants wade into the frigid water from the Bar Island sand bar.

It was the fall of 1990 and COA was unveiling a beautiful

monitors ready to pull out swimmers at a second's notice,

new pier. But not everyone was a fan. The school barely

there's an hour-long, mandatory meeting beforehand,

had any boats to speak of at the time. What was the point

and there's the simple decree that all you have to do is

of building such an expensive pier?

jump in the water to be considered one of the swimmers.

"Students were grousing about us spending money

This, says Ken, is meant to prevent people from pushing

on the pier," Ken Cline, faculty member in environmental

too far past their limits.

law and policy, remembers. On a fairly chilly day he was

"I want people to feel comfortable asking for help. I

talking with a few of his students after class, when the

don't want anyone to feel like they have to go all the way if

contentious subject of the pier came up followed by the

they can't."

usual complaints.

The swim has changed over the years. As the crowd

"One of the students said, 'Well, if nothing else, it'd be

grew, the dock became too small to launch and keep

a good place to go swimming'. So a couple of us decided to

track of the swimmers. For a few years, a boat carried

jump off the pier. I don't know who made the suggestion,

swimmers to just off Bar Island and they jumped from

but someone said we should all swim out to Bar Island. So

there, swimming back. Then the crowd grew too large

that's what we did," continues Ken.

for the available boats. Swimmers now gather at the

As Ken and four students walked down to the dock, he

Bar Island sand bar, wade into the water, and head for

recalls, "another student got caught up with the energy

the COA dock. It might not be as dramatic a start, but

and jumped in, in her underwear."

the swim still represents a rite of passage, one that is

The next year the group swelled to fifteen. The

challenging, fun, and singular.

numbers kept increasing. In 2015, 138 students, staff,

"I love the swim," says Ken. "I think it epitomizes some

faculty, and alumni turned out for the frigid traverse.

of what we want our students to do with their education.

People have shown up painted blue, in costume, with

We want them to try something that they haven't

inflatable animals in tow, and in their birthday suits.

done before that might be a little bit scary, a little bit

There are concerns. Frenchman Bay is quite cold and

uncomfortable. I think we draw students who are willing

not everyone is a skilled swimmer. COA works to keep

to take those sorts of risks and try new things. And it does

the swim safe. Numerous boats line the passage with

give them a sense of accomplishment." - -Rob Levin

6

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

NEWS

DECEMBER IN PARIS

December marks a pivotal time in

and Augustin will be joined by fifteen classmates who have been participating

climate change negotiations, as

in Doreen Stabinsky's course Practicing Climate Politics. Doreen is COA's

nations are expected to finalize

faculty member in global environmental politics, agricultural policy, and

a new agreement on actions to

international studies, and currently holds the Zennström Visiting Professorship

address the problem. They will

in Climate Change Leadership at Sweden's Uppsala University.

conclude the discussion in Paris at

The class enables students to become conversant in the language and

the 21st Conference of the Parties

concerns under discussion-studying the negotiation processes, the positions

to the United Nations Framework

of various countries and country groupings, and the ways to engage in the

Convention on Climate Change.

official processes to press for a stronger outcome. Thanks to such intensive

Among those gathering in Paris

work, the COA delegation often takes a leadership role among the international

will be COA musicians Angela

youth at the meetings.

Valenzuela '17 and Augustin Martz

This will be the second UNFCCC for Sara Velander '17. She has been

'17 of the group Agua Libre-free

following issues of forests and agriculture in the negotiations, and will focus

water. They are spending the fall

her work in Paris on understanding how the process can deliver adequate

term on an artistic residency,

support for adaptation efforts of vulnerable communities. Sara also expects

creating music to promote climate

to be involved outside the negotiations, where youth and others meet, make

action.

connections, and build strategies.

The language of international

While Sara would like to see true change, she is not nearly so optimistic.

negotiations can be dense and the

"We have lost some hope in what countries can achieve under this convention

challenges of addressing climate

at this point in time," she says, speaking also for Earth in Brackets, COA's

change in fair and just ways

student climate change group. "We believe that Paris is a stepping stone

seemingly intractable. Angela and

for mass civil society mobilizations where alliances will be built and cross-

Augustin are working to transform

community organizing networks can be established. That's why we are calling

the complicated texts and issues of

it the Road Through Paris, rather than Road to Paris."

climate justice "into songs that can

reach people and strengthen the

Students are blogging on earthinbrackets.org; Angela and Augustin can be found at

climate justice movement."

agualibre.net.

Says Angela, "We believe that

art is a force that empowers and

connects humans and life on Earth.

Music can be the wind that sets into

movement the necessary cultural

and societal changes in times of

crisis. We want to use this power to

create a space of unity that allows

for true dialogue to happen and real

solutions to flourish."

Through songs like "El Hombre

de Papel" (Paper Man) and "El Ultimo

Glaciar" (The Last Glacier), the pair

discuss the problematic aspects of

climate change while offering a vision

for a different kind of world. "El

Ultimo Glaciar" ends with words of

hope: "May our teardrops become a

wide river that unites our veins, that

irrigates the possibility of imagining,

of rising up for the infinite worlds

As Angela Valenzuela '17 and Augustin Martz '17 perform at a United Nations Framework

Convention on Climate Change gathering, Christiana Figueres, executive secretary of

that rise up and sprout, spread out."

the UNFCCC, watches intently. Says photographer Omer Shamir '16, "They became the

As the meetings begin, Angela

superstars of the conference."

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

7

ISLANDS

Kate Shlepr '13

Sometimes I wander until I find a nice spot outdoors, and then I sit. I close

my eyes and think or dream, listen to the sounds around me, and focus on

the blankness of my eyelids-so that when I open my eyes | am swept away

by just how vibrant the land is. Here, on a wharf in the town of Westport, on

Nova Scotia's Brier Island, bright sun skitters over a swift-moving passage

between this island and the mainland, while the white of two churches and

a fish plant stands stark against green leaves. Our research team worked

hard over the last three days, pressing through prickly rose, raspberries, and

mud in order to keep the straight transect lines necessary to complete a gull

nest census. I was exhausted at the end of it, but I have since showered and

prepared dinner, and now I find that I am simply happy. Tonight we will use

the data we collected to generate a map of gull nest densities. We hope this

will tell us more about the factors influencing the reproductive success of the

gulls we monitored throughout the breeding season. We hope, too, that the

map will help the Canadian Wildlife Service managers carrying out a wetlands

restoration project on this island; they have observed how gull guano alters

the soil chemistry where the birds nest, making it likelier that roadside weeds

will outcompete rarer bog plants.

Closing out my fifth summer of seabird research, I have come to accept

that there is only so much running away you can do on a small chunk of rock,

say one mile long and one-quarter mile wide, like COA's Great Duck Island.

Add a limited residential population and what is often non-existent Internet

and phone service, and you find that you really are on a little island. This kind

of space to think and see without distraction is uncommon in the modern

world, and it is part of what makes doing research on islands unique. There

is a change of pace that comes with fieldwork-early mornings and lots of

exercise, family-style meals born partly out of practicality for a small crew

with a limited food supply and partly out of desire to enjoy the company of

others after hours of sun and wind. Islands themselves have a unique ecology,

one seemingly simple enough to fully observe, understand, explain. And there

is a felt history in island townships carried in old schoolhouse photographs

and known family names, or by scars in the earth where granite quarries once

prospered. These qualities, shaped by the physical isolation of islands, provide

settings for experiences not found anywhere else.

It was curiosity about field biology that led me to islands as a COA

undergrad; I now appreciate how few other colleges can boast two thriving

island research stations. Like many students on their first venture to Mount

Desert Rock or Great Duck Island, I had little idea of what to expect but was

nevertheless fully involved from the moment I stepped onto the boat. These

days my island hopping is concentrated a bit further downeast, but I am still

pulled toward Great Duck where my eyes were opened to a discovering and

wondering that will carry me through this lifetime.

Kate Shlepr '13 is working on her master's in biology at the University of New

Brunswick, Canada.

8

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

View of Mount Desert Island from the Edward McC. Blair Research Station on /

Photog

COA'S ISLANDS

Mount Desert Rock

Great Duck Island

Twenty-one miles out to sea, battered by waves,

coursed by wind night and day, lies isolated Mount

Desert Rock. On it stands Mount Desert Light and the

several outbuildings that comprise the Edward McC.

Blair Marine Research Station. Each low tide, hundreds

of seals haul out on the bare ledges, the highest of

which rises only seventeen feet above sea level. Above,

gulls circle and cry without end, while every thirty

seconds the foghorn moans. A few plants tenuously

grow on the three-and-a-half-acre island, but nary

a tree. On the nation's entire east coast there is no

lighthouse more exposed, none further out to sea.

In 1972, Steve Katona, COA's founding biology faculty

member and former president, took a boatful of

students out to the Rock and discovered-much to

most everyone's surprise at the time-that whales

were diving near the island. Soon the Rock (or MDR)

became a platform for scientists from Allied Whale,

COA's marine mammal research program, also

founded by Steve Katona. In 1998, the college acquired

MDR from the Coast Guard.

Each summer as many as six hundred seals, upwards

of four hundred herring and black-backed gulls, and

three dozen eiders can be seen daily. Humpback,

finback, and even northern right whales are lured

to the region by the upwellings of deeper, colder,

Students come to the island to conduct research and

nutrient-rich waters. Joining them are harbor porpoises

collect ecological data. Each day they rotate a watch

and common and white-sided dolphins. Add to that

from the tower from 0600 to 1800, an hour on, maybe

population COA students and alumni researchers,

an hour-and-a-half off, searching for whales and

along with scientists from such institutions as Woods

porpoises, noting fishing boats and tankers. At the

Hole Oceanographic Institute and the National

height of each tide and at its ebb, counts of the seal

Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration, and you

and bird populations are also taken.

have a busy Rock. In the late summer of 2015, eighteen

COA students lived on MDR for a two-week field

In 2014, Grace Shears '17 and Teresa Bompczyk '17

studies class in marine mammal biology. Before the

were among ten students conducting research on

students arrived, and after, a number of carpenters

the Rock. Grace was studying seal morbidity and

worked to repair the damage wreaked on the buildings

mortality, characterizing wound types and severity.

by Hurricane Bill and Tropical Storm Nemo. The repairs

Teresa analyzed planktonic communities to identify

are funded by a grant from the Mars family.

the zooplankton found in different locales, depths,

and seasons. She gathered the plankton by dragging

For faculty member Sean Todd, who oversees the

a large, fine-meshed net behind one of the dinghies to

Blair Research Station, "the Rock is a stepping stone

collect water samples-a process known as a plankton

to the marine environment. We look out from our

tow-then viewed the results under a microscope.

island to the waters that surround us.

Life on both

There is no better way to display the excitement and

of COA's island research stations-the Rock and Great

dedication of these young scientists than by excerpting

Duck Island-requires independence, initiative, and

a few pages from their entries to the daily log.-DG

self-reliance." And that, adds Sean, echoed by John

Anderson, who runs research on Great Duck, is an

Looking southward from the Mount Desert Rock research station.

essential part of the learning.

Photographs by Izik Dery '17.

10

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

shop.vac

Leaving Frenchman Bay's Porcupine Islands behind as COA's M/V Osprey heads to Mount Desert Rock.

FIRST GRACE WRITES:

July 26, 2014, Saturday

So we got an article today about great white sharks in New Brunswick and there was a picture of their fins. We realized

the fins Sophie [Cox, a summer researcher from the United Kingdom] and I saw are definitely not basking sharks,

more likely great whites, not to mention the mysterious splashes we've been seeing lately. Chris [Tremblay '03, station

manager] also said they saw a "basking shark" fin the other day, but he says he's suspicious it may have been a great

white. I want to see one so badly!

ITT [COA's summer high school session, Islands Through Time, see page 23] is coming Wednesday, and that reminds

me, Sean brought out the disentanglement gear, in case we get any more entangled seals (hopefully not, but it'll be really

great to have out here).

Teresa and I went swimming yesterday and we found out today from the CTD [an instrument that measures the

ocean's temperature, depth, and salinity] that the water is still just 50 degrees F. Haha. So we've been swimming in 50

degree water with potentially large great whites, huzzah. Well, it's been a long day.-GS

July 27, Sunday

Fairly uneventful day. Chris has us practicing landings in the cove and that was pretty fun.

We had one whale earlier today, but none since then. I've been working on the list of MDR birds I promised Matt

[Messina '16]; I've got twenty-three species so far. Today I've seen a puffin, some double-crested cormorants, semi-

palmated sandpipers, spotted sandpipers, gannets (juvenile and adult), and the first common terns of the season! Very

exciting.

I really can't wait to see a humpback; the blows we saw today looked suspicious: not quite fin whale blows, but no

flukes so we weren't sure. It was fairly foggy so we figure they were fin whale blows distorted by fog. (We were sure they

weren't humpbacks, not sure if they were fins.)-GS

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

11

July 31, Thursday

Today was hectic, but fun. It was quite

foggy this morning and we were limited

in our activities, though it cleared up

later on. I helped Porcia [Manandhar

'17] band chicks and took groups of ITT

kids to see seals. We launched Delphis

[one of MDR's dedicated inflatable

boats] and set the drift buoy [to

measure currents by drifting in them

as the position is logged via GPS] while

Sophie, Megan [Comey '17], and Chris

did a plankton tow.

Tomorrow will be busy; we're

getting the second group of ITT kids.

Chris is also taking a couple days off.

Greenlight Academy [a Connecticut-

based high school field camp] is coming

out Monday and leaving Friday. Sadly,

I'm leaving with them.

To end this entry on a good note,

we saw fin whales super close to the

island today! Porcia had never seen a

whale; it was exciting.-Cheers, GS

August 1, Friday

Sophie and Porcia saw a pod of white-

sided dolphins this morning, which was

pretty cool; they saw a large group later

on the whale watch. Toby [Stephenson

'98, COA's boat captain] came a little

after lunch and we launched Sali [a

buoy equipped with hydrophone and

recorder to document underwater

sounds. The names of MDR craft are

based on the Latin terms for marine

mammals: Sali is short for Balaenoptera

physalus, the fin whale; Delphinus delphis

is the common dolphin.] Chris showed

us how to charge the batteries for the

recorder. Since Chris will be gone for

two days, we will be going out tomorrow

to change the batteries and listen for

whales. It's going to be exciting because

this evening we saw two fin whales and

a huge pod of dolphins feeding right

near the buoy! I cried when I saw the fin

whales lunge feeding, you could even

see the bait ball! [A tight spherical ball

that small fish form in an attempt to

evade predators.] And we saw so many

shearwaters and gulls. Well, I've got to

go help with the fire for marshmallows

Top to bottom: Chris Tremblay '03, station manager, awaits supplies for the Rock with

Khristian Mendez '15 in the foreground; looking east into fog from the MDR research

and enter some data.-(newly dubbed)

station; a seal basks on the rocks of Mount Desert Rock.

Capt. Shearwater.

12

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Sophie Cox, a visiting undergraduate from England, surveys the wildlife around Mount Desert Rock through the high-powered

binoculars known as "Big Eyes." Behind her on the laptop is Elizabeth Beato, a summer research assistant with Allied Whale. The surveys

are conducted in conjunction with NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

August 2, Saturday

We just had an amazing sunset and a good day. We went out and changed the batteries on Sali and saw lots of gannets,

one of them actually made a sound. I've never heard a gannet before, it was neat. Due to a knee injury, I didn't do too

many watches today, but I did go up the lighthouse stairs this morning with some ITT students to look at two fin whales.

Others saw a basking shark and a minke.-Cheers, Shearwater

AND NOW TERESA TAKES OVER:

August 23, Saturday

We unfortunately have witnessed two incidents of intentional homicide and cannibalism here on Mount Desert Rock

it

was Megan. She's gone crazy. Just kidding! It was just an evil black-backed gull attacking herring gull chicks, one

yesterday and today. I think it's too fat and lazy to go scavenge for other food.

A dead seal is currently swashing back and forth in the cove can't tell what kind because it's been nibbled on and is

missing a face. I'm actually really freaked out by it.

Abby [St. Onge '17] cooked a delicious meal of spaghetti and garlic bread (thank you Abby) last night. Hopefully

tonight we can cook kabobs over a nice, non-toxic fire, as Colleen [Holtan '17] and I rescued some driftwood from the

western cove yesterday evening.

Other than that it's been pretty quiet out here. There was a "humpy" in the NE earlier today, but our whale friends

haven't been around for the most part.-Teresa Bompczyk

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

13

August 26, Tuesday

Lots of excitement this morning. There were two fin

whales (on the "small" side) hanging around not too far off

shore, so Chris allowed Sophie, Anastasia [Czarnecki '18],

and myself to ride out in Delphis with him to get a closer

view. It was amazing to see whales that close in such a

small boat definitely gave me a better perspective on

their size. [Sean notes that all activities close to whales

are strictly regulated; students and staff comply with the

minimum approach distances.]

Attempted to collect plankton data but only

succeeded in getting four horizontal tows, one vertical,

and two CTD casts due to the tide. However, Megan

and I were able to drive Delphis. Steering a boat is so

different from a car-you always have to be checking and

correcting your heading. I get distracted too easily on a

boat.

Tried fishing yesterday off the northern side with no

bait and an unimpressive lure. I was surprised to catch

five fish-three pollock and two rusty orange fish I can't

identify. It was so different from freshwater fishing,

especially in Buffalo, New York. Usually I go to this super-

disgusting part of the Niagara River by my old house,

throw a worm on the hook and wait at least a half hour

before anything even bites. I'm so happy I was able to fish;

it brings back great memories.

We were seeing a seal with some gear or line caught

around its neck, but it hasn't been spotted for a while.

Grace has permission from Sean and Rosie Seton [COA's

marine mammal stranding coordinator] to save it (if

possible) next time it hauls out.

Grace, Megan, and I went swimming in the cove this

afternoon to wash up. We haven't showered since we got

here. It's actually not too bad, except the perpetual guano

on my clothes. I swear, they remember me from when

I banded their chicks and are exacting revenge with air

A black-backed gull on the research station's chimney.

raids of excrement. Or it could be that I've been sleeping

on guano-covered rocks for a few nights.

August 29, Friday

I received warnings about the cold, the wet, and the

I'm leaving for the season today, along with Colleen,

outhouse bucket before coming out here. I was also

Scott, and Dan [DenDanto '91]. The summer went by so

warned of the island's beauty, and how I'll never want to

quickly and I've had so much fun and learned a lot. Mount

come off. But no one told me about the night here the

Desert Rock is probably the most beautiful, interesting,

night on MDR is by far the most captivating and awe-

inspiring place I've ever been, and I would be honored

inspiring aspect of this place. I honestly don't understand

and so appreciative if I were able to come back. There's

how people can even stand to sleep inside on a warm,

a lot of projects and data waiting to be started and

clear night.

collected hopefully next summer that will happen! Until

There's the sound of real, live ocean waves to lull you

then.-TB

to sleep, a gentle salty breeze, the light from the tower

slowly revolving around in the cove there's a dazzling

P.S.

display of bioluminescence, fishing boat lights reflecting

off the water in the distance, and the stars. I've never

SLEEP OUTSIDE, at least once. You are so conveniently

been so truly amazed in my life. Billions of distant stars

resting beneath one of the most clear, unpolluted (from

are visible here it's so humbling. Literally, if there's

light), beautiful night skies. Take advantage of it! Don't let

a heaven, mine would be an unceasing night on this

the gulls flying at night trick you into thinking they're huge

island.-TB

meteors

14

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

POETRY

NO MAN IS AN ISLAND IS A WOMAN

CAROLINA MOON

Eloise Schultz '16

Arlo Cristofaro-Hark '17

Everything went to the wind last night;

Your Mother,

the ocean grabbing at what it could,

my Grandmother constellation

the island howling in reply.

soft skin

translucent veins

as if

This morning's calm, shy light

on water. No sign of storm

while she lay there

I could see straight into her heart

but what the waves threw up.

Sophie ventures out

like

with a bucket and returns

like

with a dead monkfish

like

draped over her forearm, fins splayed

like

like

between her fingers. She pries open

its mouth to reveal a pale, fleshy tongue

behind rows of needle teeth.

like

like

Its slime skin has lost its luster,

dulled by sun and heat.

Three hundred

Sixty five

For most out here, the sea is home:

Crossword puzzles

danger comes when we wash

Pool cues

ashore, where soft meets hard.

She sang,

Carolina moon,

But to the saw-whet owl seeking

keep shining

refuge in the generator shed,

the island sings: survival.

I bet you that she

is still up there somewhere

To the tern darting through the air,

white wings moving like scissor blades,

she calls come: here, no harm will come to you.

And to the downy chick scurrying across the rocks,

small of its neck gouged to a bloody mess

by beak and talon, she says the same.

This is not to suggest that the island intends

to deceive; rather, she welcomes everyone

with the same enthusiasm, then watches

them die with the same indifference.

The island understands what is

expected of her: to receive.

But she is necessarily

her own self. All her life,

she has been practicing

separation; think how long

she has strained to hold

herself above the waves.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

15

COA'S ISLANDS

Mount Desert Rock Great Duck Island

There's an almost eerie quiet to an offshore island. Walk just a few

steps inland from gull cries and wave surges and you can hear the

flight of insects within the silence. Spend time and the island begins

to reveal itself: which bird nests where, what rocks are stable, how

field merges into forest. Eventually, it almost seems possible to sense

with the eye of a gull or guillemot. So it is with COA's "ducklings," the

students who spend the seabird breeding season on the narrow, mile-

long Great Duck Island some eighteen miles south of campus. Here

the nocturnal Leach's storm petrel and plump black guillemot flock to

breed each summer-more here than to any other known locale in the

eastern US. Herring and black-backed gulls along with eiders also nest

on the island, joined recently by the Atlantic puffin.

In 1998, COA acquired twelve acres of Great Duck, sharing the rest

of the island with the Nature Conservancy, the State of Maine, and a

summer resident. Each summer, guided by biology faculty member

John Anderson, students at the island's Alice Eno Field Research

Station begin the day with a climb to the lighthouse tower to count and

record every visible living creature. Later the thirty-five representative

herring and black-backed gull nests selected at the beginning of the

season are monitored. Once the chicks have hatched from these nests

they are weighed and measured daily: "chick check." Tiny metal and

plastic bands are placed around the legs of these chicks-and as many

other birds as possible-to better observe their individual destinies.

The day ends with a communal dinner and the nightly log. Every week

a careful sweep of the island is made to count all nests.

Beyond recording daily findings, most students do their own field

research. Some begin the summer with a well-planned project; others

wait to survey the island upon arrival, finding their subject in the

questions that arise. "They come up with a project themselves. We're

giving them the chance to experience graduate school early on," says John.

Through observation, field research, and archival searches, students are amassing a thorough ecology of this one

small island-zoological, botanical, geologic, human, and historical. And dramatic changes have been observed-

an increase in eagles, major movements of gulls, the introduction of puffins.

At 0600 on June 8, 2015, this year's crew-Brenna Castro-Thews '18, Nina Duggan '18, Nadia Harerimana '18,

Rachel Karesh '16, Meaghan Lyon '16, Audra McTague '19, and Ite Sullivan 18-boarded COA's M/V Osprey and

departed into a misty sunrise for Great Duck Island. Over the weeks, as the students watched petrel, gull,

guillemot, and puffin emerge from egg to nestling to fledgling, as they observed eagles foraging the very chicks

they had cradled in their hands, they came to a new understanding of place, themselves, each other, and the

greater cycle of life.

The following excerpts, taken from the group log during each of the seven weeks of the 2015 Great Duck Island

season, reveal the students' remarkable commitment to the human ecology of an island.-DG

Fog rolling in partially obscures the lighthouse on Great Duck Island, but doesn't touch the flagpole. Photographs by Nina Duggan '18,

except as noted.

16

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Meaghan Lyon '16 holds a black

guillemot chick during "chick check.

June 12, 2015 Friday

The day dawned cold and a little windy. John woke us up at 0640 as usual. Nina saw savanna sparrow chicks. Audra

worked on her project, mapping her nests and recording the eggs and chicks. Brenna found something amazing: herring

gulls dove on her much more than black-backed gulls as she was sitting next to the nests. After dinner Ite, Brenna, and

Rachel went out in the drizzle and a petrel flew into them. They held it and were very happy.

June 18, Thursday ISLAND COUNT DAY!

The day dawned slightly overcast and warm with lovely mirages to the east. After a basic tower count we set off round

the island. Audra [who was looking at herring and black-backed gull vocalizations] finally got a recording of the gulls'

nest switch call. [Both male and female gulls take turns feeding and tending their young. As one returns from offshore,

it announces its arrival to the other.] Rachel [who was using game cameras to determine the petrel's pattern of return

to their deep, inland burrows] set up three game cams around Atlantis [near the boathouse, see page 18] to try to see

petrels and found a burrow with three adults in it. Meaghan [who was researching her senior project on guillemot nest

site selection and survival] found eight guillemot nests between Atlantis and the boat house. Ite learned to tie various

knots and looked at algae. Nadia saw two fights between herring gulls. Audra banded her first chick by herself! Brenna

and Nina went on a plant phenology walk and brought back lots of samples as well as photographs.

NB: Roses up to the north end of the island are flowering. Irises are also flowering, as are the ones in our eastern

meadow! But eastern meadow is only just flowering while those at north end are fully open.

June 19, Friday ALCID DAY-Nineteen razorbills seen by John at tower count this morning

The day dawned drizzly and dark. The ducklings slowly trickled downstairs for breakfast. John made us French toast with

homemade bread. Yum! After breakfast everyone sat around writing notes and going through journals. Brenna started

to identify plants and Nina [who was looking at the interaction between gulls and eiders] went through eider photos.

The cloudy weather blew over and blue sky and sunshine started peeking out at around 1100. Nina and John spent time

in the tower. At 1247 an adult peregrine falcon took an adult guillemot right out of the air just left of the boat shed. It

eventually dropped it somewhere around Puffin Point after being pursued through the colony by gulls. The harbor seal

kept porpoising up, seen last at 1419.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

17

June 24, Wednesday

private hell

&

ofsky's

Patience's chick [a late-nesting

gull whose nest was next to the

lighthouse tower steps] is moving

within its wet shell about to be a

freshly hatched chick. The adults are

becoming slightly more aggressive

stood

now and it'll be interesting to see

where their territory/range expands

to. Nina had been searching for

cabin

depsycho

common eider from the tower

all morning: seventeen common

eider adults and nine chicks. In

airstrip

the afternoon she did not find any

common eider, but she did find

wren chicks and a mountain ash.

Slough

From 1300 to 1500 Rachel and Audra

despond

banded gulls on the east berm

totaling forty-one chicks: thirty-six

herring gulls and five great black-

backed gulls. Meaghan trailed along

disods

searching for black guillemot nests

and brought her total island nest

count to fifty-one nests! Rachel

checked on her petrel cameras

after the banding fest. By the end

of the most beautiful day thus far

Patience's chick successfully hatched

from its shell, fluffy and chirping for

Mum.

blondie

June 30, Tuesday

sun

The day dawned with a beautiful fog

surrounding our tower. It lifted by

W.

0740 and we were all ready to play

in the warm sunshine. Meaghan

sat in the tower from 0800 to 1030

Grand

Canyon

watching the feeding rate of the

black guillemot along the west berm.

Most chicks were found alive and

my

well, but there was one dead. "Late

N

Gull" has three chicks, John's favorite

black-backed chick is fat and sassy,

and everyone is happily surprised by

the lack of dead chicks after our rainy

silver

day. An adult bald eagle came from

Puffin

the north, diving down on a group

keeper's

death

of five common eider chicks and one

adult female. The eiders all dove

simultaneously just escaping the

grasp of the eagle. The eagle then

lighthouse

attempted it a second time, but the

eiders escaped into the depths of the

ocean yet again. John is full of songs

Great Duck Island, by Robin Owings '13.

today by a variety of artists and time

18

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Clockwise from top left: a black guillemot egg;

adult herring gull; Audra Novine McTague '19

assists Bik Wheeler '09, MPhil '16 in banding a

great black-backed chick. Photo by John Anderson.

Sunlight reflecting off the ocean illuminates the undersides of clouds

hovering near Great Duck Island. At such moments, students on the

island would abandon their work to admire the sky.

periods. A great black-backed gull stalked the chick under the tree by the path but had no success. Meaghan saw the

chick later in the evening with the parent! Black guillemots and gulls were copulating on the rocks which seems late in the

season, but they may be re-laying. [When eggs are lost to weather or predation, birds sometimes attempt replacement

clutches.] A crow was seen carrying a chick (herring gull) from the east colony in the afternoon. Also an eagle (mature

bald) came into the colony twice, once in the morning and once in the evening, but nothing was taken.

N.B. The Indian pipes are coming up!

July 2, Thursday EAGLE HELL DAY

Meaghan checked on her chick check nests at Point Colony and found three wet chicks! Rachel collected her SD chips but

only got pictures of rabbits. John, Ite, and Brenna discussed the Civil War during tower watch. Between 1452 and 1828 we

had eight separate eagle attacks! One eagle got an adult herring gull on one of the later attacks. John made us enchiladas

and beans and rice for dinner and we talked about suicide bombers. Eagle attacked again after dinner!

July 9, Tuesday PUFFINS ON POINT (Nesting)

Meaghan spotted two great blue herons as well as two juvenile and one adult bald eagles. We got our first confirmed

sighting of a puffin with a fish in its beak, which means chicks!

July 15, Wednesday

The day did not dawn. Everything was damp and layered in thick fog. The air began to warm by 1200 and the fog cleared

a bit, but the water was still not visible. Meaghan spent time painting, Audra wrote and studied constellations, and all the

while the gulls remained relatively quiet, uninterrupted by eagles.

20

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

July 18, Saturday

The day dawned with cool, damp air and we felt rain driplets during tower count. The air remained cold and the wind was

strong out of the southwest, which occasionally brought in some rain. Tower watch was cold but doable. We saw several

flying chicks, razorbills, Atlantic puffins, double-crested cormorants, and the usual. Point Colony smelled like death

(rotting chicks). Meaghan found dead chicks in nest eight and nine. She also found four new nests and there are most

likely more because there were over 136 individuals on the water from Blondie Bay to north of the point. Rachel went

petreling and found a chick in a burrow along the road and it was tiny tiny! The adult was in the nest too. Around 1426 a

juvenile eagle went into the west field and grabbed a chick. It was a large chick with flight feathers. We saw it being eaten

up the field along the path to Blondie Bay. It was a day for walking and adventuring in the forest and updating data. Nina

made a beautiful and delicious curry and dahl for dinner and we shared stories of our past.

July 23, Thursday ISLAND COUNT-(Rachel, Meaghan, and John's season comes to an end. ITT starts soon.)

The day dawned finally clear! The days of fog are over. During island count Meaghan saw a black guillemot go into an

unmarked crevice along the slough, which is so weird. Those rocks roll/are very unstable and have very limited spaces for

nests, but the individual was carrying a fish (ground gunnel). Just before noon, Nina, Meaghan, and John saw two mature

bald eagles fly over the east berm and slowly rise above the tower. Then they latched their talons together and dove

for the colony spiraling downward as the colony rose like a cloud in protest. No more babies they called with traumatic

alert calls. The eagles stopped and flew on but did it one more time before heading north along the west berm. It was

interesting that the herring gulls did not rise in protest until after a dive was made. Nina went to Blondie Bay and saw a

mass of hummingbirds on the fireweed on the path. Eagles (juvenile) were hanging out there too, soaring high above the

woods. The sunset was beautiful and cool as we enjoyed one of our final nights on the magical Great Duck Island.

Two gulls-a black-backed (left) and herring (far

right) pursue a bald eagle that had come in close

to the lighthouse to attack the gull colony.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

21

Grubbing for Petrels

Anne Hurley '15

The Leach's storm-petrel, a small, dark seabird that seldom even rests to eat, nests in deep burrows within the sod of Great Duck

Island's woods. To band and thus monitor the young, students are trained to reach into the burrows and pull out the tiny fluff of

a chick-known as petreling, or grubbing for petrels. Anne Hurley '15, a "duckling" from 2012, wrote about the experience in her

senior project, Coming In By Going Out: Notes for Olive, a collection of experiences in nature written for her young niece.

My first time grubbing for petrels was on a humid, sweaty day-the kind where you're tense from the heat and the only

thing worse than being hot is being bitten all over by mosquitoes while sweating. We checked hole after hole, the soil and

tree roots biting at our skin as we reached deep into the nests, our faces beet red and our hands puffed, scratched, and

sore from the mosquito bites. We hit two that were empty; I prepared to grub the third hole. My arm was stinging as I

began reaching into the burrow. I sunk my chest into the ground as my arm stretched. I was just about to reach the limit

of my arm when I felt a soft shell-like object covered in what felt like long peach fuzz. At the touch of this surprise I drew

my arm back quickly, but then continued forward to ever so gently grab hold of the shelled cotton ball. I heard a "peep"

from below the ground. I tried not to panic as it sat in my grip-it was so light, so vulnerable, and sitting in my hand. I

was terrified of my hand twisting the wrong way, for fear of injuring delicate life. When I finally reached the opening of

the burrow and this new chick saw its first rays of light, my body filled with an overwhelming amount of guilt, adrenaline,

and love. She was no bigger than a cotton ball; she even looked like a cotton ball, but dyed with black walnut ink. It's

been said that petrels smell like grandma's clothes that have been stored in the attic. I held her, scooped between both

hands, and brought her close to my nose. Breathing slowly, I smelled the soft scent of Nana's dress that hung lamely in

the back of her closet. We banded the chick, leaving our signature deliberately behind.

22

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

ISLANDS

THROUGH

TIME

Audra Novine McTague '19

In the summer of 2014 Audra Novine

McTague was one of sixteen high

school students participating in Islands

Through Time, or ITT, an immersion

in the human ecology of islands.

Guided by faculty members John

Anderson (zoology, behavioral ecology),

John Cooper (music), Helen Hess

(invertebrate zoology, marine biology),

Sean Todd (marine mammology), and

Karen Waldron (literature, writing),

students spend time on Great Duck

Island, Mount Desert Rock, and

campus. For Audra, the twelve-day

intensive was not enough. What follows

is adapted from her essay applying to

PROVIDE

the COA class of 2019.

GREAT DUCK ISLAND, August 1, 2014

The stars were brilliant that night.

I sat and stared upon the haggard,

wooden foundation of what used

to be the home of one of the three

Photo by John Anderson.

lighthouse keepers on the island.

Only one of the homes remains,

with a boathouse that has been

the fresh, salty air as it entered my

to know what I thought about such

transformed into a bunker, to my

nostrils and continued down, filling

subjects. Why do I think as I do?

left and down the hill. Behind me,

my lungs; the smell of nothing but

Why have I never thought that way

the towering white lighthouse had

nature.

before? My brain hurt, but it was a

just revealed itself earlier that day

For at least ten minutes this was

good kind of hurt, as if something

as the fog lifted for the first time

all that occupied my mind. But as

had forced a door open that I didn't

since I had arrived on the island. The

I came to, I realized that I had to

know was there.

tower shot out an eerie red light that

get up early the next morning, so

Then, as quickly as they came, the

almost gave the night a supernatural

I made my way down the winding

thoughts left. As I lay down, my mind

impression, completing a revolution

path, through the gull colony, and

became silent and centered around

every twelve seconds.

into the boathouse. That is when the

the atmosphere that enclosed me,

The sights, the sounds, the

conversation that was just held on

as the crying of the gulls just outside

smells were magnificent: the

those old, haggard boards flooded

the door and the continuous blows of

contrast between the blue of the

my brain. My views on the world,

the foghorn held me in my sleeping

sea, the white of the ocean's mist,

on science, and my own religious

bag. I lay with my eyes facing the

the brown of the beaten rocks, the

beliefs had just been challenged

northernmost window and watched

red of the rugosa rose blossoms

by my teacher, John Anderson. Not

the sliver of moon afloat above the

and berries, and the green of lush

simply questioned, but tested with

earth turn into a crescent of fire as

brush and bushes; the crackling of

a bombardment of alternative

it sank below the western horizon.

the campfire, the beating of the flag

theories, queries on why I believe

Without a thought in my head and

on the pole behind me by the wind,

what I do, and reasons as to why he

with this intense feeling of deep

and the whistling of the wind itself

believes what he does. Never have I

happiness and content, I drifted off

blowing from the ocean, through my

thought about such deep ideas, nor

into a peaceful slumber as the island

hair, past my ears; the coolness of

has anyone ever been so curious

lulled me to sleep.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

23

In Their Own Words

COA community members tell us about their lives in this new section; while

we edit the conversations, they remain "in their own words."

Collected and edited by Marni Berger '09

Island Activism

Hiyasmin Saturay '15, creator of the film Pangandoy: The Manobo fight for land, education and their future on the struggles

of the Philippine indigenous group, Talaingod Manobo

Islands mean a lot to me. I come from a

country of 7,107 islands-and I grew up

on an island, the island of Mindoro in

the Philippines.

Both my parents were activists

and were helping stop a mining

company from coming into our area

and displacing hundreds of indigenous

people. We had to leave in 2006

because a lot of my parents' colleagues

were getting killed. I always remember

the sacrifices they made, the work they

started, how it's grown. When I think

about that, it's like, How can you stop

working when some people have offered

their lives for it?

Coming to COA with that

background helped me to understand

Benito is one of Talaingod's leaders. Says Hiyasmin Saturay '15, this work "has

human ecology, that it's really

made me more humble, definitely, just to see that you're one part of a bigger

movement."

important to see things in more than

one perspective and address problems

in more than one perspective.

My senior project was kind of a going-home project. It was also a part of my organizing work here in the US. I am

currently in Long Beach, California, part of a progressive arts organization, Habi Arts. Habi means weave, weaving

the different arts, looking at the connections among different struggles. We believe that people coming together is

what's going to create change and try to use our art in organizing workers, youth, women to connect the struggles of

migrants and women in the US to the problems in the Philippines. For example, we encounter migrant caregivers here

who are being exploited and abused on the job. Basically, the same kind of political-economic system that causes their

displacement to the US is the same system that affects the indigenous people that I made my documentary about.

I was in Talaingod, Davao del Norte to do my project for three months. The paramilitary was close by the communities

I went to, so it was pretty scary to do that kind of work. But I just trusted the people. They knew how to protect me and

protect themselves. They have a community that functions, that aims to be sustainable; it's very democratic. I saw the

seeds being planted there-what can happen when people come together. It's so inspiring that people see their school

as very important and try hard to keep it going.

I think that's only really reaffirmed for me that I will be committed to this work wherever I am, and if something

happens, I'm OK to give my life to it, just like so many others. I wouldn't let fear stop me.

Hiyasmin Saturay's film was part of her senior project. For access to the film, or her senior project presentation, email

hsaturay@coa.edu.

Marni Berger '09 is a writer living in Portland, Maine.

24

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Above: Hiyasmin Saturay 15-in blue,

upper left-with children from Talaingod.

"The most important thing is to stay close

to the people. And learn from them."

Below: Motivated students study even

outside their classroom.

Photos by or courtesy of Hiyasmin Saturay '15.

Chile's González Videla research station in Paradise

Bay on the Antarctic Peninsula.

Below: Alex Borowicz '14 and penguins at Salisbury

Plain, South Georgia. Photo by Tanya Cox.

Antarctic Research

Alex Borowicz '14, Antarctic field guide and PhD student in ecology and evolution at Stony Brook University, New

York

When I sailed in the morning toward the Antarctic peninsula my first time, it

was absolutely breathtaking-you go from two days in open ocean and all of a

sudden you see these snow- and ice-covered mountains, and you reach this place

that is stark, and it's harsh, and you feel how desolate it is, but also how palpable

life is there because it's such a challenging place to live.

I spent two winters as a general marine biologist guide in the Antarctic.

My first season I was a senior, it was right before my senior project term. I put

together an introductory whale talk, an intro seal talk, an oceanography talk,

one on whaling history, and one on fish and fisheries. I didn't do a climate

change talk, but I always throw in little nuggets of climate change. The Antarctic is the most rapidly warming place on the

planet-you can look at pictures of glaciers melting back year by year and how all the organisms are responding. You can

see it right there. But you still run across people who don't believe it.

There isn't a lot of large-scale science going on in the Antarctic because it's so challenging. There's a lot of basic

biology that we've inferred from just a few data points, which isn't quite enough. So we make a lot of generalizations.

When I see something interesting that hasn't been represented in the literature to my knowledge, it's exciting: a penguin

with the wrong color eye; a humpback whale with really weird barnacles and skin lesions that I've never seen anywhere.

Each one of those moments is this feeling of exploration and the promise of answers to questions that hadn't been

thought yet.

I come from Wisconsin and there's not a lot of ocean out there, so COA was my introduction to the marine world-I

worked out on Mount Desert Rock and on COA's boat, the Osprey. My PhD program is in a quantitative ecology lab, using

math and statistics to tackle complex ecological questions which can be used to get at issues of population dynamics

and other fairly large-scale problems in ecology. I'm hoping to look at how changing climate variables are affecting

populations at both large and finer scales in the Antarctic. One thing COA taught me was to ask questions broadly and

think about how things work on vastly different scales.

26

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Clockwise from top left: two crabeater seals on an

ice floe; chinstrap penguins returning from the sea;

an iceberg adrift in Antarctica's Bransfield Strait.

Photos by Alex Borowicz '14, except as noted.

Island Education

Alice Anderson '12, science educator at the Hurricane Island Center for Science and Leadership on Hurricane

Island, Maine

A lot of people jump to thinking, islands are isolating. But islands are also really connected-in different ways than we

necessarily think of.

Island environments are great teaching tools because they are this miniature version of the world that ideally can be

scalable. On Hurricane Island, it means students can come out and get really excited about the natural environment,

but not feel totally overwhelmed. Our main mission is supporting Maine youth in science, sustainability, and leadership.

Within the science realm we focus on getting kids excited about making their own observations and informing their own

questions around the natural world.

One program focuses on the terrestrial landscape; after seven days students can really have a good understanding

of the top twenty-five plants and identify them as they go around the island. It is so important to help kids connect and

be familiar with the place that they are in, which is really valuable in empowering them to see that they could be a field

scientist-or have skills to identify things around them. I see kids light up in the field, really engaged and sort of dropping

all of those thoughts, like I'm too cool for learning, because they are just genuinely excited about what they are finding.

We've also collaborated with programs like Eastern Maine Skippers which Todd West '01, the Deer Isle-Stonington

principal, helped spearhead. It's a multi-school program targeted towards students in the fishing industry who tend to

be at a higher risk of dropping out because the lobstering industry is so lucrative right now. The classic response is, Why

would / sit in a classroom when I can make more money hauling traps in one morning than teachers make in a week? It's getting

those kids re-engaged in learning that's relevant to them, making sure they're getting some of the critical at-the-table,

on-the-water, and in-the-office skills that help them be good lobstermen and owner-operator businessmen long-term.

A big part of how we live out here is that we're off the grid. We have our own solar panel system, composting toilets,

a constructed wetland that filters our graywater. And we have a really intentional design around the campus that helps

students monitor our collective energy use and learn about what it is like to live off the grid. COA has a lot of that, but

when you really have to embrace it as your lifestyle because there is no backup to plug into, it definitely changes you. You

think, How much do / really need on a daily basis? How can I cut back on my impact on the natural environment? That's been a

huge part of how I live now-just recognizing how important it is to walk the talk when it comes to sustainability.

Photo courtesy of Hurricane Island Center for

Science an Leadership.

28

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

A northern elephant seal family on Race Rocks; a

juvenile golden eagle calling with Mt. Baker in the

background. Photos by Alex Fletcher '07.

Bottom: Alex Fletcher '07.

Photo by Virginie Lavallée-Picard '07.

Solitary Reliance

Alex Fletcher '07, winter Race Rocks Ecological Reserve guardian and Vancouver Island farmer, British Columbia,

Canada

I grew up on a big island, surrounded by islands, living at that transition between

landscape and seascape. You have that rich intertidal zone-there's a lot of energy,

there's a lot of life, a lot going on there.

My work at Race Rocks is a mix of caretaking the island, coordinating and

supervising students and visitors to the island, monitoring and observing wildlife and

human activities within the protected area, and reporting infractions such as marine

mammal disturbance or illegal fishing in the protected area. The light station has been

in operation for over 150 years but in the nineties federal government budget cuts

resulted in the station being de-staffed. That is when Lester B. Pearson United World

College of the Pacific took over management of the area, ensuring its protection and

continued availability for research and education.

The setting is very dramatic: we're in the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca so

we're partly protected to the south, but we're also exposed to the open Pacific. We're

RACE

surrounded on one side by the mountainous peninsula of Olympic National Park in

the States and on the other side by Vancouver Island. The Race Rocks archipelago has

pretty rich wildlife. It's a haul-out for California and northern sea lions, seals, and the

ROCKS

most northerly rookery for northern elephant seals. It's also a pelagic bird nesting ground.