From collection Jesup Library Maine Vertical File

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Search

results in pages

Metadata

An Historical Account of the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory 1898-1993,1994

An

Historical Account

of the

Mount Desert Island

Biological Laboratory

1898-1993

MOUNT

DESERT

LABORATORY

The Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory

SINCE 1898

For the Leaup Library,

with affection and big

thanks for so many years

of friendly help

y H m

8/12/94

THOMAS H. MAREN

As a prelude to our centennial celebra-

tion, we at MDIBL are pleased to present

this overview of the scientific history of

MDIBL by Thomas Maren who has been a

distinguished investigator at the Labora-

tory for 41 years. In Dr. Maren's account,

you will learn about the founders of the

Laboratory, about the move to Salsbury

Cove and about the scientists who shaped

our scientific mission and whose influ-

ence is still felt today.

Thomas Maren was educated at

Princeton University, receiving the AB in

Chemistry in 1938 and the MA in English

in 1942. He began his scientific career as a

chemist with Wallace Laboratories (1938-

41) where he worked on the chemistry of cosmetics. Later, at the Office of Naval

Research (1943-46) he studied chemotherapy of tropical diseases.

In 1947, he was appointed instructor in the Department of Pharmacology and

Experimental Therapeutics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine where he

worked until 1951 studying drug actions on the pituitary gland. He graduated from

the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1950. From 1951 until 1955, he

was Group Leader in Pharmacology at the American Cyanamid Company where he

led the initial development of carbonic anhydrase enzyme inhibitors and began the

work that still occupies him today, centering on the chemistry and pharmacology of

CO2-carbonic anhydrase systems that are widespread in the animal kingdom and have

led to the discovery of new drugs that inhibit this enzyme. These have proved useful

in the treatment of a variety of diseases, notably, glaucoma and altitude sickness. Here

at the MDIBL he has exploited the advantages of comparative animal models in

research.

Dr. Maren was one of the founders of the University of Florida School of Medicine

where he was Professor and Chairman of the Department of Pharmacology and

Experimental Therapeutics for twenty-two years (1955-77). Since 1978, he has held the

position of Graduate Research Professor in this department. At the University of

Florida, Dr. Maren has been deeply involved in the basic science education of medical

students.

AN HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE

MOUNT DESERT ISLAND BIOLOGICAL LABORATORY: 1898-1993

Thomas H. Maren

Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics

University of Florida College of Medicine

Gainesville, FL 32610

As we approach the 100th year of this Laboratory, it seems appropriate to put forth a short

history, particularly for the younger people and all those who aspire to that definition. There are

rich lodes of material, some not readily accessible except in the main office of the Laboratory. I

have drawn on accounts by the following and these are documented in the bibliography:

Mary Frances Williams and Max Morse (Harpswell days), E.K. Marshall, Roy P. Forster,

J. Wendell Burger, Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen, Marty McManus and, most importantly,

THE BULLETINS available from 1921 to the present.

My introduction to MDIBL was by Homer Smith. He had encountered a problem close to

my own research: why sea-going fish did not have a renal response to a carbonic anhydrase

inhibitor while all other vertebrates (except Crocodilia) respond with typical HCO- diuresis.

I made a preliminary solution to the problem and have been here for the ensuing 40 years. I

had a double affiliation to the Laboratory since a major part of my training was in the

Pharmacology Department of E. K. Marshall at The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Thus I

grew up with the remarkable advantage of twin loyalties and friendships to these heroic figures

of our past.

This essay is divided into seven segments covering in each case some 10 to 20 years and

attempting to give, in addition to the social and academic picture, a brief but necessarily

superficial account of the types of research done through these many decades. My account of

our first 60 years inevitably has perspectives lacking in the recent history. In the earlier time this

institution was the shadow of a few great men; now there are many players and their lasting

influence is not always clear. I hope that some future historian will record in more critical detail

the manifold accomplishments in all of these times.

I.

Beginnings, Harpswell Laboratory, 1898 - 1921

This Laboratory was founded by John Sterling Kingsley (Fig. 1), a professor of biology at

Tufts who visualized in the small town of South Harpswell, Maine, a summer school for

undergraduates in biology at Tufts and elsewhere, and also a research laboratory. He was a man

of remarkably affable character and fine scholarship and to some degree the Harpswell

Laboratory was a reflection of his personality. He was born in 1854 in upper New York State,

graduated from Williams College in 1875, and acquired an Sc.D. degree from Princeton in 1885.

He went to Tufts in 1892. At South Harpswell which was a few miles from Bowdoin College

and one and one half hours by boat from Portland, he built the small laboratory that you see in

the background of Fig. 2, and in Fig. 3 a characteristic picture of Kingsley gathering specimens

on the beach. He also built a small cottage for himself near the Laboratory, and for many years

served as director, business manager, host for scientific visitors, and editor of many of the

journal articles destined for publication. As he put it, "This biological station is one of the most

unpretentious structures one could imagine as readily will be understood when it is said that the

whole plant-land, building and permanent equipment-cost within one thousand dollars."

The permanent equipment was two rowboats, assorted dredges, abundant glassware, several

microscopes and a nucleus of a library on morphology and marine biology. There were no

pumps, no running water, no electricity. Warmhearted Mrs. Kingsley hosted women scientists

with the help of her daughter Mary. Social occasions comprised Dr. Kingsley and the

1

ladies of his family and staff who entertained guests in the Laboratory's big room which

smelled of lemonade, cookies and formaldehyde (Fig. 4). There were no automobiles,

and the local stable rented horse and buggy for those who wished to ride about or visit

friends. Simplicity and congeniality abounded. Many of the families lived in tents. The shop

talk was lively, especially with visiting scientists. Kingsley's personality welded the

Laboratory together into a close and congenial community. His energy seemed inexhaustible

as was his capacity for friendship. After some seven or eight years, however, they

abandoned the teaching program, and the Harpswell Laboratory became entirely a

research facility. Undergraduate instruction, he said, was a drawback to the investigators.

Interestingly, this pattern was repeated many years later and several times after the move

to Salsbury Cove.

However, they were not isolated. A

boat from Portland left every two hours,

making libraries in Portland available, and

equipment could readily be brought back

every day. During the 23-year period a

hundred papers were published. Most

unfortunately, the abstracts of publications

from the Harpswell Laboratory, which is

Volume I in our own series, are missing (but

the titles of papers have survived) SO that

our bibliography begins in Vol. II after the

move to Salsbury Cove. Representative

papers from Harpswell included the follow-

ing: catalog of marine invertebrates of

Casco Bay, basic work on the anatomy of

the skull in Squalus acanthias, morphology

and development of eye muscles and nerves,

essays on sexual plants, and most

importantly, early pioneering work on the

cleavage of eggs in Cerebratulus by the

noted Japanese morphologist, Yatsu.

Kingsley also wrote a widely-used textbook

on the comparative anatomy of vertebrates.

At the end of World War I, matters

changed at Harpswell. Kingsley departed to

the west coast; Ulrich Dahlgren and

Herbert V. Neal became the dominant

figures who were to play vital roles in estab-

lishing the Laboratory at Salsbury Cove.

Figure 1. John Sterling Kingsley. See text.

Their lives will be briefly outlined now.

Dahlgren (Fig. 5), despite his foreign-sounding name, was a classic American patrician, an

ancestor having fought with George Washington and a grandfather who served as an admiral in

the Civil War who invented a gun which brought fame and money to the family. Dahlgren was

born in Brooklyn in 1870 and entered Princeton in the autumn of 1890, graduating with the Class

of 1894 and getting a master's degree in biology two years later. He never went on for the Ph.D.

but stayed at Princeton as a stalwart of the Biology Department until his death in 1948. He was a

biologist of the old type, interested in speciation and specimen collections. He came to

Harpswell in about 1908, had a home there and published a classic text called Principles of

Animal Histology, built up largely from his own observations. When Kingsley left the

2

Harpswell Laboratory in 1919, Dahlgren became Director and, as we shall see, was a vital

engineer in the move to Salsbury Cove.

The other moving

spirit in those latter

days at Harpswell and

then Salsbury Cove

was Herbert V. Neal.

He was born in

Lewiston, Maine, in

1869, the only native

in our cast. He was

graduated from Bates

and in 1896 received

the

Ph.D.

from

Harvard where he

began work on the

vertebrate skull. After

a year in Munich he

went to Knox College

in Illinois and stayed

until 1913 when he

Figure 2. Harpswell Laboratories and living quarters.

moved to Tufts for

the rest of his life;

there he was greatly admired as a teacher. His research was chiefly in embryology, particularly

development of eye and head muscles and nerves, and the skull of elasmobranchs. He came to

Harpswell early in its history and was Associate Director from 1908 - 1915. He was a prime

factor in the move to Salsbury Cove, and the first building was named for him. He became

Director in 1927. As described by Wendell Burger, "His wife, Helen, was an energetic Yankee,

able, self-righteous,

and considered her-

self the Queen Mother

of the Laboratory, as

though she and Her-

bert had given it birth.

As faculty without

resources but with

competitive aspira-

tions, they were thrust

into an environment

of affluence." Their

patroness, the wealthy

and socially impecca-

ble Louise de Koven

Bowen, had helped to

buy the 70-acre

McCagg tract (the

land east of the post

office on both sides of

the road and extending

Figure 3. Kingsley (right) collecting.

to the Bay) and stip-

ulated that the house, barn and four acres of land (Bow-End) belong to the Neals for life and the

Laboratory was to keep it up. Mrs. Bowen believed that professors (at least professor-directors)

should live in style; Neal had a car and chauffeur as well as a motor boat, appropriately named

The Dahlgren. We shall never know what Ulrich thought of this.

In later years

Neal(with H.W.Rand)

published a famous

text on Comparative

Anatomy of the Ver-

tebrates. To his own

research he brought

both scientific and

artistic skills and

questions of the place

of man in nature. He

died in 1940; Helen

Neal lived on for

many years in Bow-

End, then in a nursing

home in Bar Harbor.

She kept keen interest

in MDIBL and visits

from younger scien-

tists.

Figure 4. Interior view, Harpswell.

II.

The Move to Salsbury Cove and

Establishment There

A new major player now appears on

the scene-George B. Dorr, a wealthy

Boston aristocrat and bachelor who had

been raised summers on Mount Desert

Island. He devoted a large part of his life to

the maintenance of the island in its natural

state and the acquisition of land to protect it

against the depredations of civilization.

Importantly, he had the ear of John D.

Rockefeller, of Charles William Elliot and

virtually all of the distinguished summer

inhabitants of the island which was

flourishing as a resort for the rich and well-

established societies of New York,

Philadelphia, Boston and Washington. The

record is not completely clear, but it is likely

that it was Dorr's idea to move the

Harpswell Laboratory to Mount Desert. In

the name of his corporation, the Wild

Gardens of Acadia, attractive land in

Salsbury Cove was acquired, which he

called the Weir Mitchell Station. This was

named for his friend, the distinguished

neurologist from Philadelphia who was

practicing cures on the wealthy and neurotic

elite women of his time by making them

virtual prisoners in their homes while they

4

were forbidden to work or think. Mitchell had no connection to the Laboratory. At a meeting in

Princeton in the Fall of 1920 with Dahlgren, Dorr and Henry Lane Eno (a long-term summer

resident and philanthropist), the basis for a land transfer from the Wild Gardens of Acadia was

laid down, and the so-called Weir Mitchell tract, 14 acres comprising the Leland house and the

present dining room and surrounding area was leased for 99 years to the Laboratory. In 1949

this was changed to perpetual ownership after conference with Wendell Burger, E. K. Marshall

and the remaining member of the Wild Gardens, S. Rodick.

In June 1921 the

FRANKLIN

laboratory at Harpswell

was packed up, loaded on

Bangor .

HANCOCK

a ship and the exodus

Skowhegan

Machine

Farmington

took place (Fig. 6). The

WALDO

Ellsworth

trip lasted 11 hours, and

OXFORD

KENNEBEC

Beifast

the Salsbury Cove site

Augusta

Pans

was established. From the

KNOX

ANDROSCOGGIN

Rockland

sale of the laboratory at

LINCOLN

Auburn

Wiscassel

Harpswell, they were able

SAGADAHOC

Bath

to build a new one, to be

g

CUMBERLAND

South

called Neal, for some

Harpswell

Emigrants' Route

Portland

June 1921

thousand dollars, which

was a virtual replica of

Alfred

the one they left behind.

YORK

(It is on this site that the

shell was used to build a

new laboratory in 1991.)

Dahlgren was the first

Director at Salsbury Cove.

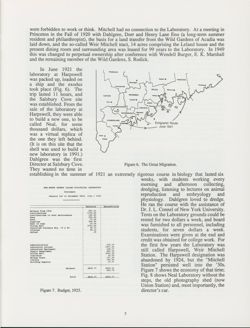

Figure 6. The Great Migration.

They wasted no time in

establishing in the summer of 1921 an extremely rigorous course in biology that lasted six

weeks, with students working every

morning and afternoon collecting,

THE MOUNT DESERT ISLAND BIOLOGICAL LABORATORY

dredging, listening to lectures on animal

Statement

January 1st to December 24th, (inc.) 1925

reproduction and embryology and

physiology. Dahlgren loved to dredge.

He ran the course with the assistance of

Receipts

Expenditures

Balance from 1924

587.31

Dr. J. L. Connel of New York University.

Contributions

1735.00

Contributions to boat maintenance

100.00

Tents on the Laboratory grounds could be

Fees

250.00

Dues

75.00

Supplies

524.99

rented for two dollars a week, and board

Rent of tent

10.00

Dining Hall

1503.44

was furnished to all personnel, including

Cancelled vouchers Nos. 75 & 86

38.73

Interest

28.12

students, for seven dollars a week.

Refund

.18

Examinations were given at the end and

credit was obtained for college work. For

Administration

332.75

Laboratory Current

1017.43

the first few years the Laboratory was

Laboratory Equipment

148.73

Supply Department

849.90

still called Harpswell, Weir Mitchell

Dining Hall

1423.38

Insurance

32.50

Station. The Harpswell designation was

McCagg Tract

137.25

Library

100.00

Building Repairs

10.07

abandoned by 1924, but the "Mitchell

Station" persisted well into the '30s.

Balance

4852.77

4052.01

800.76

Figure 7 shows the economy of that time;

Total

4852.77

4852.77

Fig. 8 shows Neal Laboratory without the

steps, the old photography shed (now

Union Station) and, most importantly, the

Figure 7. Budget, 1925.

director's car.

5

In 1923 another

major player ap-

peared,

William

Proctor, who leased

two additional parcels

of land to the west of

the Wild Gardens

tract and built what is

now known as the

Forster Cottage and

the Kidney Shed as

his laboratory. He

was an amateur col-

lector and made sub-

stantial contributions

to the Laboratory in

the early days. There

was continuing accu-

mulation of land from

the Rockefellers and

other

contributors

Figure 8. Laboratory (Lewis), Darkroom and Director's car, 1928.

such as Mrs.Maxfield,

Asa Wasgat and Mrs. Bowen. This is all documented in the manuscript of Dr. Wendell Burger.

Dr. Warren Lewis (Fig. 9) and his wife,

Dr. Margaret Reed Lewis, were principal

actors at Harpswell and were part of the

move to Salsbury Cove. The Lewises were

great pioneers in cell culture and made

enormous contributions to the field. Other

early investigators and contributors to the

organization and politics of the Laboratory

were Harold D. Senior, Professor of

Anatomy at NYU, and Milton J. Greenman,

Director, Wistar Insitute in Philadelphia.

The trustees present at a critical meeting in

1927 were Mrs. Bowen, A. C. Bumpus,

Dahlgren, Milton Greenman, Neal and

Proctor. It was at this meeting that Proctor

was defeated in a vote for president;

thereupon he left the Laboratory in a rage

and became an enemy for the rest of his life.

I shall now describe briefly the work of

E. K. Marshall and of Homer Smith and

their interrelations.

Eli Kennerly Marshall (Fig. 10, at

age 64 with Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen at age

35) was born in Charleston, South Carolina,

Figure 9. Warren Lewis (1870-1964) and Margaret Reed Lewis (1881-1970). W.L., M.D., Johns Hopkins,

1900. Professor, Anatomy, Johns Hopkins. M.L., B.S. and D.Sc Goucher. Research Associate,

Anatomy, Johns Hopkins. Picture taken in 1960, when they were still at work at the Wistar Institute.

6

in 1889 and grew up

in that genteel city in

classic southern tra-

dition. He attended

the small excellent

private Charleston

College where there

were eight in his

graduating class, and

he was the only

chemist. His profes-

sor suggested that he

go to Johns Hopkins

for graduate work,

and so at the age of

19, this shy, inexperi-

enced, untravelled

young man went to

Baltimore. After sev-

eral years of an excel-

Figure 10. E. K. Marshall (see text) and Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen in 1952.

lent life, socially and

B.S-N., born Copenhagen, 1918. D.D.S., 1941, Ph.D. (Copen-

scientifically, he re-

hagen) 1946. Professor, Biology, Case Western Reserve 1964-

ceived the Ph.D. in

1971. MDIBL President 1982-1985.

Chemistry in 1912.

He went for a brief

time to Abderhalden's laboratory in Germany where he accomplished little, but quite on his own

got the idea for the determination of urea using urease. Upon returning to Baltimore, he applied

to the Department of Biochemistry at The Johns Hopkins Medical School. However, the profes-

sor, Jones, assured Marshall that there was nothing more to be done in biochemistry and

suggested some other occupation. Marshall walked upstairs where he found the professor of

pharmacology, John J. Abel, already a world-class figure. Abel gave him the opposite advice

from Jones, said he would take him into the department with one small condition, that Marshall

attend medical school. This came about, and Marshall received the M.D. from Hopkins in 1917.

Meanwhile, he had made a major strike, discovering a quantitative method for the determination

of urea using the enzyme urease. He became a captain in the Medical Corps in 1917 stationed in

Washington, and there he discovered one night working in a lonely back room on some chemical

experiments another shy, skinny young man named Smith enlisted from Cripple Creek, in

Colorado where he had been selling vacuum cleaners. The two became friends, and Marshall

vowed that when the war was over, he would see that Homer Smith got an advanced degree,

possibly in medicine, from Johns Hopkins. Somehow this did not work out, and instead Smith

got the Sc.D. from the Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health. We shall return to his

story in a moment. At the end of the war Marshall, virtually just out of medical school, was

appointed Chairman of the Pharmacology Department at Washington University in Saint Louis.

He stayed there only two years and returned to Hopkins in 1921 as Professor of Physiology and

began work on the vitally important issue of active transport of dyes and other substances by the

kidney. In 1923 he discovered that phenol red was actively secreted by the mammalian kidney.

It was the first clear demonstration of active transport in any organ and was opposed by

essentially all the leaders in the field, particularly Cushny in Edinburgh and Richards at the

University of Pennsylvania. He was undaunted by all of this. He did not belong to the fraternity

of renal physiologists anyway, and he was never one to walk away from a good fight.

In 1925, reading the literature he discovered aglomerular fish and, after conversations with

his friend Alan Chesney (later to become dean of the medical school at Hopkins and a summer

visitor to Maine), Marshall decided to come to Mount Desert Island in search of

aglomerular fish, notably, the goosefish (Fig. 11). He came in 1926 with a student, Allen

Grafflin, and with his wife participated in the rough and ready living conditions at the Labora-

tory. They had bad luck with obtaining live goosefish, but he returned in 1927 with Grafflin

and did the crucial

experiments showing

renal excretion in the

complete absence of

glomeruli which, in

addition to his impec-

cable work on the

mammalian kidney,

made it certain that

urine could be formed

by tubular secretion

as well as glomerular

filtration. A finding

of the greatest im-

portance was that the

aglomerular fish did

not excrete glucose,

i.e. it was not handled

by the tubules. This

led to the develop-

Figure 11. The aglomerular goosefish, Lophius piscatorius.

ment of xylose and

inulin as the markers

for glomerular filtration rate, in the hands of Smith, Shannon and the NYU school. Marshall's

great contributions in this decade were reviewed in Physiological Reviews in 1934. At MDIBL

in 1926, to his surprise, he once again found Homer Smith who had been a Fellow at Harvard

and was now studying the diffusion of acids and bases into arbacia eggs and their effect on cell

division. Alas, it is not clear what brought Smith to MDIBL.

Marshall and Smith were very different personalities, and perhaps it is not surprising that

they did not become more intimate. Marshall was rather austere, reserved, had fairly limited

interests, did not delve very much into literature or music or art and had no taste for outdoor

sports. His great strength was original and imaginative investigation. He was totally honest,

outspoken and selectively profane. He had the old-fashioned habit of addressing colleagues of

all ages by their last names; at least he did in Baltimore. In Maine he was considerably more

relaxed and did use first names in addressing us.

Smith, on the other hand, had universal interests in music, literature, theology as well as

science. His books Komongo and Man and His Gods were required reading for new arrivals at

the Laboratory. Marshall brought few students here and only worked at the Laboratory from

about 1927 to 1934. Smith, however, had a major stake in the Laboratory and occupied the

Kidney Shed for some 30 years, extending well into the '60s. He brought dozens of young men

and a few women, mostly physicians, into his laboratory where he had a profound effect on their

future lives. Three of them are shown with Smith in Fig. 12. Another is Stanley Bradley who

became Chairman of Medicine at Columbia. Smith's major work was the magisterial

monograph, The Kidney (1951), singly written and encompassing the entire world literature.

There have been few books in the history of science with this scope and critical acumen.

Although Marshall's home in Salsbury Cove was chiefly for vacation after 1934 when he

succeeded Abel as Chairman of Pharmacology at Hopkins, he still exerted tremendous influence

in the Laboratory by visiting the young people at work and pointing out to them that much of

what they were doing had been in the literature for several decades. Marshall's particular

8

favorite was Roy Forster of whom we shall speak later. Roy had once introduced Marshall with

a line from Carlyle, "Genius is the transcendental capacity for taking trouble," which he

emended to fit Marshall, " for making trouble."

It must have been Marshall

who got Smith interested in the

kidney, although there are no

extant records on that point. But

by 1928 Smith was interested in

water equilibrium in various fish

and published a very important

paper on the body electrolytes in

elasmobranchs. In 1930 he and

Marshall collaborated on a

monograph, (Biol. Bulletin,

1930) in which they related the

evolution of vertebrates to the

evolution of the kidney in fish,

that presumably arose in fresh

water. There the glomerulus was

needed as a filter; fish then

migrated to the sea where the

glomerulus became either lost or

degenerated. This theory had

very wide appeal. The power of

Figure 12. On dock, 1953. Right to left: Homer Smith

Smith's reasoning, his grasp of

e text), Henry Heinemann, Julius Cohen,

biology, evolution and paleon-

Al Fishman.

tology and masterful prose is best

seen in his 1932 paper in Quarterly Review of Physiology. His strength in thinking and

exposition appears in the "perfect matching between the large and small scales of his subject"

(see Homer Smith Dedicatory issue of THE BULLETIN, Supplement, Vol. 28). Smith used the

Laboratory for war research in 1942, and when work was reestablished, he resumed high

activity, becoming president from 1950 - 1960. Smith established musicales, dances,

expeditions around the island and was generally interested in younger people, speaking readily to

all of us, particularly those who had sense enough to penetrate a rather rough facade. He became

Chairman of Physiology at New York University in 1928, where he remained until his death in

1962. The brief partnership of Marshall and Smith in those years in Maine (they lived but 200

yards apart) was admirable scientifically; Marshall handled secretion, Smith water balance.

Returning to the state of the Laboratory in this decade, it was certainly thriving on an

unpretentious scale and low budget. Dahlgren was Director from 1921 to 1926 and President

from 1937 to 1946. He had contact with the wealthy and influential visitors to the island and

instituted weekly seminars by distinguished professors, many from Harvard. In this era some 43

papers were published on plant and invertebrate biology, still with an emphasis on morphology.

These are listed in the 1929 announcement. There was only one paper on the kidney, that of

Marshall reporting the discovery of aglomerular function in the goosefish. The most prolific

workers in this period were Warren and Margaret Lewis, already mentioned as pioneers in cell

culture, who developed time-lapse photography showing previously unappreciated aspects of

cell division.

Unfortunately, there are no abstracts in Vol. II (1921 - 1930). In this period there was an

attempt to publish Communications of the Laboratory (1926 and 1927), but this proved expen-

sive and difficult. In its place, and beginning with Vol. III (1931 - 1950) the present system of

annual abstracts was adopted. The budget for each of the years, 1925 and 1926, was about five

9

thousand dollars. Some of these details are seen in Fig. 7. By the end of this decade, in addition

to the Neal Building, the Kidney Shed, which was originally Proctor's collecting station, was

activated as the laboratory of Marshall and Smith, and a bit later the Lewis, Halsey and Hegner

laboratories were built. There was a small director's office, dark room and our crowning

disgrace in disorganization and age, the tool shed. On the Old Route 3 was the Emery House

Dining Room and the old schoolhouse, now the lecture and meeting room, Dahlgren Hall. All of

this was unchanged until the early '70s.

III. 1931 - 1952

There are BULLETINS for the years 1931 to 1941 with no further publication until 1950. The

1950 number, the last of Vol. III (12 numbers), summarizes the work between 1942 and 1949.

The 1950 BULLETIN contains the all-important bibliography of the Laboratory for the period

1929 to 1949. Vol. IV, No. 1, gives abstracts for 1950, 1951, 1952.

The 1950 BULLETIN lists 217 papers (including abstracts) of which 69 (30%) are concerned

with kidney, heart and electrolytes. Of these, two thirds came from the heavy hitters, Forster,

Marshall-Grafflin, Smith-Shannon. Although MDIBL was gaining a formidable reputation in

the renal field, the large majority of workers-about 20 senior investigators in 1946 - 1950 (the

same as in 1930)-were in other fields. These include invertebrate behavior, ecology, anatomy,

cell culture, growth of cancer cells, reproduction. Philip White, Lankenau Hospital, Philadel-

phia, in these years had an important research and teaching program in tissue culture, housed in

the Hegner laboratory. He was the first to grow cells (plant) in wholly synthetic media.

THE BULLETIN for 1950 reflects only dimly the heroic and successful efforts of Dr. Roy

Forster to restore the Laboratory after its neglect during the war years when the dock was blown

away, the buildings somewhat damaged and no funds were available for reconstruction. A

remarkably lucid account, however, is given in a pamphlet dated 1946, of the war years,

reconstruction, plans for the future, and gentle appeals for money. Due in part to the friendship

of Mr. Amory Thorndike who had roots in Maine on both sides of his family and who was now a

year-round resident, Roy was put in touch with influential people on the eastern seaboard who

contributed to the rebuilding of the Laboratory. Dahlgren was succeeded as president by Dwight

Minnich from 1946 - 1950. During all this time Roy Forster was Director.

The bibliography for these 20 years shows work on renal and cardiac function in fish. We

see the beginning of attention to isolated tubules in various species, continued work by Marshall

in the relation between glomerular and aglomerular fish, Robert Pitts' careful analysis of

phosphate excretion in fish, and further comparative studies by Smith and his group among the

elasmobranchs, teleosts and seals. A major theme was the methodology for measuring

glomerular filtration rate here and at home (for the Smith group at NYU). The Lewises

continued to be fabulously productive with work on cell culture, the growth of cancer cells in

vitro. Marshall left his long shadow in the Laboratory in the person of Allen Grafflin, who

contributed greatly to the knowledge of the fish anatomy and electrolyte excretion.

A main player during the '30s was James A. Shannon (Fig. 13), later to become most

notable as the first director of the National Institutes of Health and in large part responsible for

the growth of this unique and marvelous organization. Shannon was a protege of Smith, and the

record shows some 10 papers on the renal excretion of metabolites and markers in the teleost and

elasmobranch fishes, some by himself and some in association with Smith. Roy Forster tells the

story about his own introduction to Shannon and to MDIBL. In 1936, Roy was completing his

thesis at the University of Wisconsin when Shannon came to Chicago to lecture at the

Federation. Roy found, to his chagrin, that Shannon had done virtually all of the experiments he

had done or was planning, and he approached the visitor after the lecture wanting some

conversation. Shannon suggested that he could talk better back in the hotel room fortified with

10

some whiskey, and so the 25-year old graduate student and the young assistant professor from

New York spent the rest of the evening swapping anecdotes about phosphate secretion,

whereupon Shannon suggested that Roy come to Maine the following summer and work in his

laboratory. Roy had never been East, but he took the risk, and arrived at Salsbury Cove, came

down to the Kidney Shed where Shannon was washing glassware, and he pitched in a hand. A

few minutes later a vigorous-appearing man came in the laboratory, and Shannon said, "I want

you to meet Dr. Homer Smith." Roy thought it was a joke, but a few minutes later another man,

a rather dark saturnine young fellow, came in and Shannon said, "Roy, I want you to meet

Dr. Robert Pitts." Roy was finally beginning to catch on when a few minutes later a tall austere

man walked in and Shannon said, "Roy, I want you to meet Dr. E. K. Marshall." Roy was

certain that it all was a dream and that he had ascended finally into a renal heaven.

Forster's engaging personality and

impeccable scientific tastes were important

assets when he was made Director a few

years later and piloted the Laboratory

through the evil days of World War II and

its later recovery. A little-known chapter in

MDIBL history is the "plague of the red

feed" in herring in 1939 - 1940 and Forster's

brilliant analysis of its cause. For the only

time in its history, MDIBL was engaged by

the Maine State Fisheries to investigate the

red tide in local sea waters and the

destructive skin and organ lesions in the

fish. Forster, with no experience or training

in mycology, working with two medical

students, found that these were separate

events: the color was a food metabolite in

the intestine, the organ lesions were due to

parasitic fungus. His work drew great praise

from professors of mycology and the herring

industry; I wonder if they knew they were

dealing with a talented amateur.

Roy went to Dartmouth in 1938, where

he has been ever since. His great love and

genius was teaching, and he was honored

many times by his college. Virtually all of

his research was done at MDIBL, where he

Figure 13. James Shannon (1904 -

), M.D.,

was the pioneer, among other things, in in

Ph.D., NYU. Professor NYU and the

vitro techniques for study of metabolism in

Rockefeller Institute. Director, NIH

renal tissue and their transport properties

1952-1968.

(Fig. 14). He had major influence on dozens

of young people here. As Humphrey Davy

called Michael Faraday, "my major discovery," Roy could have said (and perhaps did say) the

same of Leon Goldstein who has given admirable scientific and administrative leadership here

for 37 years.

The Laboratory was open in 1941, but only a modest amount of work was done. No

BULLETIN appeared for this year (which would have been 1942 issue), but the titles of work are

recorded in the 1950 BULLETIN, pages 15-16. In 1942 the Laboratory was leased to New York

University for pharmacologic study of mustard gases, under Homer Smith and David Karnofsky

(1950 BULLETIN, page 17). The Laboratory was closed in 1943 and 1944; in 1945 Director

11

Forster was in residence, perhaps alone, working on diuresis in aglomerular fish and planning for

the future.

Wendell

Burger

(Fig. 15), Professor of

Biology at Trinity

College (Connecticut)

succeeded Roy as di-

rector in 1947 and

Smith became Presi-

dent in 1950. By that

time Marshall had re-

tired from work at

MDIBL but continued

summers here until

his death in 1966.

His research in Balti-

more was very com-

pelling. As he had

done many times be-

fore, he abandoned

the research that

Figure 14. Roy Forster (right) ready for deep-sea fishing, circa 1960.

drove him to Maine

See text.

and which was so

productive, for an en-

tirely different type of work, first in the chemotherapy of bacterial diseases, then in World War II

on malaria, later on on drugs that affected the endocrine system, and finally on the pharmacology

of alcohol. I have written elsewhere a biography of the life of this remarkably productive and

interesting man (see Bibliography).

The

1953

BULLETIN

covering the years 1950 -

1952 contains but 22

abstracts, some quite long,

reflecting two to three

summers' work. Thirteen

(59%) were on renal-

cardiovascular

topics.

Inspection of these, partic-

ularly the 1952 section,

shows that indeed things

were heating up to what

Forster called the "summer

mecca of the kidney world."

Figure 16 shows the

Laboratory during this

period (and the next 20

years). Figure 17 gives the

seminar program for 1952,

showing the remarkable

Figure 15. J. Wendell Burger (1910-1987). A.B. Haverford,

richness of the current

Ph.D., Princeton. Professor of Biology, Trinity College,

science.

1936-1975.

12

IV. 1953 - 1961

My family and I arrived in the middle of the night on July 20, 1953. Early the next

morning there was a knock on the door, and there was Homer Smith, whom I had only seen once

before, carrying in one arm his little son Houdi and in the other arm a bundle of wood, which he

proceeded to put in our fireplace and start the fire for us on that cold, but now very friendly,

morning. I was then

working at the American

Cyanamid Company in

Stamford, Connecticut,

where we were devel-

oping the carbonic anhy-

drase inhibitors.

The

company had generously

given me one week to

come to Maine which,

added to my two weeks

vacation, gave me a little

time to work with Smith,

Henry Heinemann, Al

Fishman and Jurg Hodler

where we showed the

absence

of

carbonic

anhydrase in elasmo-

branch kidney. I was

regarded with some sus-

picion because I was an

Figure 16. MDIBL aerial view, 1952.

outsider in academia,

working then in industry. But there was some aura of respectability from my five years with

Marshall at Hopkins, where I also received my medical training. In that era the Laboratory had

one telephone in the dining room and one in the secretary's office. The entire secretarial staff

was Sally Murdaugh who worked half time. The other employee was Nelson Mitchell, the

redoubtable Mainer who was

at home at sea (but could

STAFF

July

18:

Raymond Rappaport.

Caretaker: Nelson Mitchell, Salisbury Cove, Maine

"Uptake of Water During Development of Am-

not swim) and land and did

Collector: A. Edwin Clattenburg. Brown University.

phibian Tissues".

Secretaries: Alison Shute, McGill University.

July

25:

Margaret H. D. Smith.

every chore with equal skill

Margaret Shute, New York University

"Some Bacteria which are Pathogenic to both

Co-op Manager: Mary Jean Chapman, University of Maine.

Animals and Plants".

August

4:

William D. Blake.

and cheerfulness, including

"Neural Control of Renal Functions in the Dog"

SEMINAR PROGRAM

August

8:

John V. Taggart

his annual ritual of kissing all

"Some Aspects of the Energetics of Transport"

Evening Seminars

August 15:

Solomon A. Kaplan.

the Laboratory wives when

July

8:

J. Wendell Burger, Trinity College.

"Control of Renal Excretion Solutes by the Auto-

'The Marine Environment of Mt. Desert Island".

nomic Nervous System"

Lot Page.

they returned in June. The

July

15:

Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen, University of Cincinnati.

August 22:

"Water Conservation in Small Desert Mammals"

"Comments on the Effect of the Autonomic Ner-

vous System on Electrolyte Excretion"

E.K. Marshall, Jr., Johns Hopkins University

total budget had then

July

22:

"Urinary Concentration Mechanisms in the Dog

"Chemotherapy Today"

and Seal".

increased to fourteen thou-

July

29:

Wilbur Doudna, Park Naturalist, Acadia Na-

tional Park.

Tissue Culture Seminars

"Beautiful Acadia".

Dr. Philip R. White

sand dollars.

August 5:

Charles G. Zubrod, Johns Hopkins University.

"Recent Observations on Diabetes Mellitus"

July

9:

"Historical Survey"

August 12:

John A. Wheeler, Princeton University.

July 11:

"General Methods. Plants and Animals".

"The Liquid Drop and the Uranium Nucleus".

July 15: "Nutrients of Natural Origin. Animal".

August 19:

James A. Shannon, National Heart Institute.

Work on the kidney had

"Advances in the Treatment of Cardiovascular

July 17: "Nutrients of Synthetic Origin. Plant and Animal".

Diseases".

July 22: "Problems and Results. Plant"

continued, on acidification

August 26: Charles C. G. Chaplin, Academy of Natural

Sciences, Philadelphia.

July 24: "Problems and Results. Animal".

"Sea Gardens of the Bahamas", Underwater

and transport with Smith and

Kodachrome Movies.

Research Reports: 1952

Informal Seminars

Forster as leading spirits.

Excretion in the Lobster, Homarus

July

11:

Roy P. Forster.

J. Wendell Burger

"Alterations in Renal Function".

Also studied were the uptake

Trinity College

July

16:

W. V. Macfariane, Professor of Physiology,

University of Queensland, Brisbane, Aus-

The extensive literature on nephridial function in the

of drugs and methods for

tralia.

higher Crustacea has dealt largely with osmoregulation little

"Physiological Studies of the Australian Desert

information exists on the handling of larger organic molecules.

Animals".

Difficulties in securing urine seem to have been an experiment-

measuring glomerular filtra-

tion rate. Most importantly,

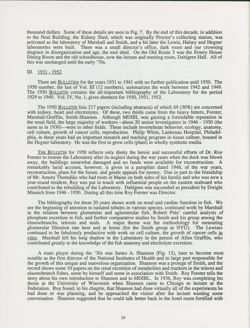

Figure 17. Seminar Program, 1952.

two major discoveries were

13

made this decade, the nasal salt gland in birds (1956) by Knut Schmidt-Nielsen (Fig. 18) and the

rectal gland in the intestine of elasmobranchs by Wendell Burger in 1959 (Fig. 15). Smith's

agreeable habit of inviting new people to the Laboratory to work on key problems resulted in the

bringing of Knut and Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen here as well as John Boylan to work on a basic

problem of why urea, a readily diffusible small molecule, was locked into the shark and

impermeable at the gill. Smith was as interested in structure as in function and brought Johannes

Rhodin, of the new breed of electron microscopists, to MDIBL.

Smith and Marshall, despite their many intellectual differences, had in common a very

strong background and orientation in chemistry, and this lent a precision and attitudes toward the

physiological work that had far-reaching consequences.

The Laboratory developed over the years

the most important tradition of bringing

students (undergraduates through post-

doctoral fellows) who stayed or later

returned to become senior investigators

and leaders of MDIBL. These include

R. Rappaport, L. Goldstein, J. Claiborne,

G. Conrad, G. Kormanik, D. Miller,

E. Swenson, K. Karnaky, R. Solomon,

J. Forrest.

A significant generation of talent was

made by John Boylan, from his keen interest

in German physiology. After World War II

there was a remarkable growth of German

renal research sparked by Kurt Kramer and

Karl Ullrich, close friends of Boylan. This

resulted in visits or work at MDIBL by these

and younger colleagues, all to become lead-

ers

in the field: P. Deetjen, H. Stolte,

Figure 18. Knut Schmidt-Nielsen (left)

E. Frömter, R. Greger, S. Silbernagl,

(1915- ). Born Norway. Ph.D.

R. Kinne, E. Kinne-Saffran. The Kinnes

Copenhagen 1946. Professor of

have become permanent, with a great

Zoology, Duke 1952-

influence scientifically and administratively.

During these years there was an admirable selection of directors, Warner Sheldon from

1950 - 1956, Alvin Rieck from 1958 - 1963. As President, succeeding Smith, in 1960 was

Marshall, and then Forster from 1964 - 1970. William Doyle, a noted anatomist and electron

microscopist had an important influence on policy, Director 1954 - 1967 and President 1970 -

1975.

Most investigators came for the entire summer. The split season was virtually unknown.

The tradition of bringing students, both medical and graduate, came into prominence. The group

at the dining hall was cheerful and companionable. Lifelong friends and sometime marriages

were made. There were important annual traditions such as the trip to Mount Katahdin, the band

concert and dance on the streets of Salsbury Cove early in August and Sunday baseball. The

tradition began of having the children of laboratory workers act as technicians and assistants.

The four parts of Vol. IV (1953, 1956, 1959 and 1962), with their attractive layout, photographs,

descriptive material, histories, and seminar schedules, tell the tale of those halcyon days. From

1930 - 1951 (excluding war years) the investigations numbered 20 - 30. In 1954 - 1961 it jumps

to about 45; most significantly the number of students grew from about five to 23 in this period.

14

Vol. IV, Part 4 (dated 1962) reflects an explosion of activity in the years 1959, 1960 and

1961. There were 115 abstracts; half were concerned with some aspect of renal, cardiac or

transport function. Eleven of these (!) came from the fertile mind, hands and pen of Eugene D.

Robin, a talented pulmonary physician-scientist from the University of Pittsburgh, utilizing not

only dogfish but seals, turtles and tunicates.

V.

1962 - 1973 Vol. 5 (2 parts) - Vol. 13. The Year-Round Programs

The work and spirit described in the previous section continued through the '60s. The

Robin group, now including H. V. Murdaugh, continued to be active and imaginative in studies

of metabolic and acid-base chemistry. Forster and new colleagues Leon Goldstein and Fred

Berglund studied nitrogen metabolism in teleost and elasmobranch. Interest continued high in

the avian nasal salt gland. In these years Dr. Franklin Epstein studied the relation of activity and

inhibition of Na+K+ATPase to salt transport in the euryhaline eel. He then went on (with

Patricio Silva, Richard Solomon and peripatetic groups largely from Harvard) to establish a

comprehensive program on the physiology and biochemistry of rectal gland secretion in the

dogfish, using largely in vitro techniques. Electrolyte and drug transport in the alkaline gland,

gill, aqueous humor, cerebrospinal fluid and brain was studied in the elasmobranch by the writer

and his students. Investigators used many species: seals, turtles, sculpin, goosefish (Fig. 11),

dogfish, flounder, eel and killifish. Chemical work came into more prominence; an exotic

finding was the bromination of aniline derivatives by the dogfish uterus, analogous to the ancient

discovery of Tyrian purple in sea animals.

Charles Wilde, a distinguished chemical embryologist, was a leader in Laboratory affairs,

Director 1967 - 1970 and President 1978 - 1979. David Rall (later to become director of the

National Institute of Environmental Health) and his colleagues pioneered studies of the isolated

choroid plexus, distribution of drugs, and fluid compartments in brain. Dr. David Karnofsky, a

world leader in cancer research, used sand dollar embryos to study mechanisms of anti-tumor

activity of metabolite antagonists used in chemotherapy. Adrian Hogben took advantage of the

absence of transmucosal potential differences in dogfish stomach (unlike the mammal) to study

relation between electrical activity and H+ and Cl- secretion. This is one of many examples

throughout, of the virtues of comparative physiology, in elucidating general mechanisms.

1971 brought a radical change, the "winter operation". Two of the country's leading

physiologists in summer residence at MDIBL for many years and both connected to the transport

field (in different ways) decided to work year-round: Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen and William B.

Kinter. Fortunately, the Karnofsky laboratory had been SO well built that it could be used in

winter; later Marshall was built to be a year-round facility. Including two or three young Ph.D.s

and assistants, there were 10 in the group: they are listed in THE BULLETIN as a separate entity

starting in 1975. Research seminars were held through the year at Bowen, in front of a blazing

fire and with proper internal warming. The 1978-80 BULLETINS (Vol. 18 - 20) gives a good

account: visitors came not only from the Jackson Laboratory, but from Harvard, Bowdoin,

Brown and far away Georgia and Stanford. Kinter's first work was on uptake and transport of

dyes, reflecting earlier work with Forster, but he then turned to ecology and environmental

problems, particularly the effect of oils on sea-bird and teleost physiology. His most able

associate was David Miller. Schmidt-Nielsen and her group studied ion and fluid fluxes in

elasmobranch and feel, including the urinary bladder of the skate. They showed that the kidney

of euryhaline feel, in fresh water, secreted water. In these different species they measured for the

first time intracellular ion concentrations. They studied the structure and function of the renal

pelvis in several species, showing how its movement "milked" the collecting duct.

Kinter died at a tragically young age (52) in October 1978; his group gradually dissipated.

Bodil continued until she retired in 1986. In 1982-85 she was active and effective as President

of the Laboratory, beginning a new sense of awareness and participation from the community.

15

The winter program brought much needed overhead to the Laboratory. When it disappeared in

1984, the advent of the toxicology program brought a new source of support. Winter work was

resumed in 1989 by a single but most important scientist, Raymond Rappaport, who began in

MDIBL in 1948 and built a world-class reputation in studies of the physical mechanism of cell

division in animals. He had been Director and President and, now retired from Union College,

works year round at MDIBL.

Although much fewer than the renal and transport scientists, those in developmental

biology (P. White, R. Rappaport, C. Wilde) were a notable intellectual force; the latter two were

prominent in Laboratory affairs. It may be argued that the "transporters" did not sufficiently

appreciate the implications of the findings in cell biology.

VI. 1974 - 1983 (Vol. 14 - 23)

During this period the Laboratory continued with new emphasis on brain and CSF in the

work of Helen Cserr. There was keen interest also in the electrophysiology of the intestinal tract

(M. Field, R. Frizzell, G. Kidder), gill (K. Karnaky, J. Zadunaisky), and heart of the "sea potato"

(M. Morad). The rectal gland continued in a leading role. Cell volume regulation was

imaginatively explored by Arnost Kleinzeller. The gill and red cell transport of carbon dioxide

and its role in formation of various body fluids were pursued by Erik Swenson and the writer.

Volume 20 (covering 1980) is illustrative of the vitality at that time. Surprisingly, 27 years

after Watson and Crick, there was still no genetics. There were about 110 people on the site, 38

principal investigators, the rest students or technicians. The fashion continued of having

laboratory "children" as assistants. At least five marriages resulted from this mix. Six or seven

families left at least one child to live permanently in Maine. These hostages are now raising

their own families. The summer season closed with a poster session and demonstrations. That

year there were 39 research reports. Only five were on kidney; 13 on rectal gland, 3 in cell

biology. The remainder, in one way or another, were connected to ion or fluid transport or

metabolism. The same proportions obtained in 1983. Again the Laboratory had excellent

directors, Richard Hays (1975 - 1979) and Leon Goldstein (1979 - 1983).

The Laboratory still held firm against formal classes, but there were (in summer) seminars

on

Tuesday evening, noon Thursday, and 8:00 A.M. Friday. The winter program had 19

seminars between late October and April, again transport dominated, but the heritage from

Kinter was plain in the several ecological sessions.

VII. 1984 - Present (Vols. 24 - 33)

The general pattern continued in the first years of this decade. Transport still dominated,

with a strong few in cytokinesis and development. In 1986 the Laboratory was established as a

toxicology research center under the domain of the National Institute for Environmental Health

Sciences. Its main thrust was the toxic effects of "heavy" metals and other environmental

contaminants on membrane transport. The program was unique in the experience and

sophistication of the local investigators in various physiological systems; much remained to be

learned about the complex chemistry of the metal ions. Fourteen of the 43 principal

investigators at MDIBL became part of the program; in later years this was reduced to 10. Dr.

David Evans became its Director. This grant provided intellectual stimulation, produced some

unexpected and remarkable results (particularly concerning cadmium) and generated important

support for the Laboratory (it should be noted that before the "winter operation" the Laboratory

had very little overhead since grants were made to principal investigators through their home

institutions). By the end of 1993 the compounds of the following metals had been studied in one

16

way or other: As, Hg, Sn, Cu, Zn, Cd. In the first year (1986), eight abstracts were generated,

and this rose to 11 in 1990. There have been two renewals of this grant which will run until

1998. The Program Director is now James L. Boyer.

In 1990 - 1992 the rectal gland continued to lead: 13 - 14 abstracts/year compared to 5 - 8

for kidney and bladder. Transport topics included volume regulation at differing salinities, gill

and liver function, localization and effect of neuropeptides, regulation of urine pH in teleosts,

work on ion channels and Cl currents. Developmental studies continued at the level of cell

cleavage in invertebrates (Gary and Abigail Conrad), and the uterus in elasmobranchs (Ian and

Gloria Callard).

1991 and 1992 saw the impact of the genetic revolution. John Forrest and his talented

group worked on cloning and sequencing of natriuretic peptide from shark heart. DNA

sequencing of Na+K+ATPase isoforms from shark rectal gland was begun. Gene sequencing

was also done on the muscarinic receptor in aortic rings and cerebellum. Studies began on the

gene expression of the yolk protein in turtles and construction of cDNA libraries from flounder

gill and kidney, and alkaline and rectal gland of shark.

Franklin Epstein became president in 1985 and David Evans was director from 1983 -

1992. The present director is David Dawson. There has continued an effective participation of

the winter and summer residents of Mount Desert Island and the neighboring mainland, notably

Ellsworth and Hancock Point. David Opdyke, who for many years studied cardiovascular

reflexes in the dogfish, inaugurated and runs afternoon tours of the Laboratory. Particularly

welcome are children of island natives and visitors. MDIBL is no longer "the best kept secret in

Maine."

Hopefully, the character of MDIBL is reflected in this essay. We have been greatly

fortunate in living in a cosmopolitan mix of research physicians, biologists, chemists,

physiologists, and pharmacologists from many countries and of different ages. We are ringed by

sea and mountain with changing light and temper-all inspiring. The future continues to

challenge.

I acknowledge with pleasure and affection the participation of Heidi Beal and Joyce Hearn.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BULLETINS of The Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory, 1921 - 1993, Volumes II (2) - 32.

The ordering of these volumes was complicated until Volume 6 and will be listed as

follows:

Vol. I.

Harpswell years to 1920. Missing; see text. Titles have been preserved, in MDIBL

Archives.

Vol. II. Yearly, 1923 - 1930, 8 numbers. These are not numbered. Not abstracts but accounts

of the Laboratory program. The 1929 issue gives a bibliography for years 1925 - 1929; the

1930 issue gives the seminar programs.

Vol. III. Yearly, 1931 - 1941: 1950, 12 numbers. Abstracts begin. The 1950 number contains

accounts of the war years and bibliography for 1929 - 1949. In 1946 an account of the

Laboratory was printed entitled "Instruction and Research." Written by Roy Forster, it is

also a gentle appeal for funds.

Vol. IV. Four numbers, each covering the three years preceding: #1 (1953), #2 (1956),

#3 (1959), #4 (1962).

17

Vol. V. #1 covering 1962 - 1964 and #2 covering 1965.

Vol. 6 - 32.

1966 - 1992. Includes Index to Volumes 2 - 6 in Vol. 6. Beginning here there is

a volume each year. Initially the year issued gave the abstracts for the preceding year, and

the volume was given that date. This was changed in 1987 - 1988 so that now, for example,

the work done in 1992 has the publication date of 1993 (Vol. 32).

These volumes, as well as the unpublished manuscripts listed below, are all available in The

MDIBL Archives.

Amos, William. Life after Summer. Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory Fifty Years

Ago. Unpublished Manuscript, April 1989.

Bowen, Louise de Koven. Baymeath. 1945. (This fine book, now out of print, is available also

at the Jesup Library in Bar Harbor.)

Burger, J. Wendell. The Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory. The Pioneer Days. 1898 -

1951. Unpublished manuscript, West Hartford, CT, 1982. (Transcribed and edited by

Marty McManus, 1989).

Forster, Roy P. My Forty Years at the The Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory. J. Exp.

Zool. 199:299-308, 1977.

Maren, Thomas H. Eli Kennerly Marshall, Jr. May 2, 1889 - January 10, 1966. Biographical

Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences, 56:313-352, 1987.

Marshall, E. K., Jr. A History of The Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory. Unpublished

manuscript. August 1, 1962 (incorporates an account of the early history of the Harpswell

Laboratory, written in 1921 by J.S. Kingsley).

McManus, Marty. An Historical Deck Chair Tour of The Mount Desert Island Biological

Laboratory, October 17, 1991.

Morse, Max. The Harpswell Laboratory. Popular Science Monthly, May 1909 (in MDIBL

Archives).

Pitts, R. F. Homer W. Smith. Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences,

39:445-470, 1967.

Schmidt-Nielsen, Bodil. A History of Renal Physiology at The Mount Desert Island Biological

Laboratory. The Physiologist, 26:261-266, 1983.

Williams, Mary Frances. The Harpswell Laboratory 1898 - 1920. A Marine Biological Station.

Maine Historical Society Quarterly, 27:82-99, 1987.

18

MOUNT

DESERT

LABORATORY

The Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory

Dedicated to Research and Education in Marine Biomedical Science

SINCE 1898

P.O. Box 35

Salsbury Cove, Maine 04672

207-288-3605