From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series II] Ticknor, George & William

licknor Georger William

FirstSearch: WorldCat List of Records

Page 1 of 3

OC

LC

FirstSearch

SOUTHERN NEW HAMPSHIRE UNIV

WorldCat List of Records

Click on a title to see the detailed record.

Click on a checkbox to mark a record to be e-mailed or printed in Marked Records.

WorldCat Hot Topics:

Select a topic to search:

Staff View

My Account

Options

Comments

Exit

Home

Databases

Searching

Results

Hide tips

List of Records

Detailed Record

Marked Records

Go to page

WorldCat results for: (su= "Ticknor,

WorldCat

Sort

Related

Related

Limit

E-mail

Print

Export

Help

George,") and su= "1791-1871.".

Subjects Authors

(Save Search)

Records found: 109 (English: 93) Rank

by: Number of Libraries

1

Prev

Next

All

Books

Archival

Visual

Articles

109

92

10

5

2

Limit results:

Any Audience

Any Content

Any Format

Search

1.

George Ticknor and the Boston Brahmins

Author: Tyack, David B.

Publication: Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1967

Document: English : Book

Libraries Worldwide: 698

More Like This: Search for versions with same title and author I Advanced options

See more details for locating this item

2.

Literary pioneers;

early American explorers of European culture,

Author: Long, Orie William, 1882-

Publication: Cambridge, Mass., Harvard university press, 1935

Document: English : Book

Libraries Worldwide: 321

More Like This: Search for versions with same title and author Advanced options

See more details for locating this item

3.

Life, letters, and journals of George Ticknor.

Author: Ticknor, George, 1791-1871.; Hillard, George Stillman,; Ticknor, Anna Eliot,, and others

Publication: Boston, J.R. Osgood, 1876

Document: English : Book

Libraries Worldwide: 196

More Like This: Search for versions with same title and author Advanced options

See more details for locating this item

4,

Life, letters, and journals of George Ticknor

Author: Ticknor, George, 1791-1871.; Hillard, George Stillman,; Ticknor, Anna,, and others

Publication: London : Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, 1876

Document: English : Book :

Microform

Libraries Worldwide: 144

More Like This: Search for versions with same title and author Advanced options

.

See more details for locating this item

http://firstsearch.oclc.org/WebZ/FSQUERY?sessionid=sp07sw02-55046-e0jms15a-qxwhfd:entit..

10/20/2004

FirstSearch: WorldCat List of Records

Page 2 of 3

5.

Catalogue of the Spanish library and of the Portuguese books bequeathed

by George Ticknor to the Boston public library,

together with the collection of Spanish and Portuguese literature in the

general library.

Author: Ticknor, George,; Whitney, James Lyman, Corp Author: Boston Public Library., Ticknor

Collection.

Publication: Boston, By order of the Trustees, 1879

Document: English : Book

Libraries Worldwide: 105

More Like This: Search for versions with same title and author Advanced options

.

See more details for locating this item

6.

Life, letters, and journals of George Ticknor /

Author: Ticknor, George, 1791-1871.; Hillard, George Stillman,; Ticknor, Anna Eliot,, and others

Publication: Boston : New York : J.R. Osgood, Johnson Reprint Corp., 1968, 1876

Document: English : Book

Libraries Worldwide: 89

More Like This: Search for versions with same title and author I Advanced options

See more details for locating this item

7.

George Ticknor's Travels in Spain /

Author: Ticknor, George, 1791-1871.

Publication: Toronto : University of Toronto Press, 1913

Document: English : Book

Libraries Worldwide: 59

More Like This: Search for versions with same title and author Advanced options

See more details for locating this item

8.

Life, letters and journals of George Ticknor

Author: Ticknor, George, 1791-1871.; Hillard, George Stillman,; Ticknor, Anna Eliot,, and others

Publication: London : Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, 1876

Document: English : Book :

Microform

Libraries Worldwide: 57

More Like This: Search for versions with same title and author Advanced options

See more details for locating this item

9.

Biographical and critical miscellanies.

Author: Prescott, William Hickling, 1796-1859.

Publication: Boston, Phillips, Sampson and Co., 1859

Document: English : Book

Libraries Worldwide: 47

More Like This: Search for versions with same title and author Advanced options

See more details for locating this item

10.

George Ticknor,

Author: Ticknor, George, 1791-1871.; Doyle, Henry Grattan,

Publication: Washington, D.C., 1937

Document: English : Book

Libraries Worldwide: 38

More Like This: Search for versions with same title and author Advanced options

See more details for locating this item

Clear Marks

Mark All

WorldCat results for: (su= "Ticknor,

http://firstsearch.oclc.org/WebZ/FSQUERY?sessionid=sp07sw02-55046-e0jms15a-qxwhfd:entit.

10/20/2004

George Ticknor

Page 1 of 4

Harvard University

Harvard@Home

Post.Harvard

HARVARD

The Harvard Store

at Ivysport

ivysport.com

MAGAZINE

Home

Class Notes

Classifieds

Back Issues

Contact Harvard Magazine

Advertise

Subscribe

HARVARD

January-February 2005

Search

Features

More features

Next

Search

Vita

Restoriog

Elm

George Ticknor

Brief life of a scholarly pioneer: 1791-1871

Article To

by Warner Berthoff

E-mail this

In This Issue

Download F

January-February

By today's standards, Harvard College before the Civil War

2005 Contents

was a provincial academy, competent (judged Henry Adams) at

preparing students to become "respectable citizens," but

George

E-mail Updates

effectively indifferent to the advances in knowledge beginning to

shape the modern world. Yet one early member of its teaching

Join our e-mail list

faculty stands as a signal exception. George Ticknor-invited in

to receive Editor's

Highlights!

1816 to become Smith professor of the French and Spanish

languages and literatures-may be called the first Harvard scholar

who would be warmly welcomed into the University faculty of

2005, just as he was the first (outside the traditional fields of

divinity and rhetoric) to hold a named chair in the humanities.

Not himself a graduate of the College, Ticknor had followed his

father, a Boston merchant, to Dartmouth in 1805, though of his

two college years he remarked late in life, "I learnt very little."

Back in Boston, his education began in earnest. He took up the

serious study of Latin and Greek with the Reverend John

Gardiner of Trinity Church and subsequently read for the law. But

his heart remained in humane learning and, with his father's

approval, he proposed to consolidate his studies at a European

university: with Napoleon's downfall in 1815, the continent was

once again open to American visitors. By then Ticknor had read

with excitement Mme. de Staël's momentous book De

l'Allemagne, with its report of dramatic advances in German

philosophy and literature, as well as a pamphlet describing the

University of Göttingen's revolutionary system of study. These

http://www.harvardmagazine.com/on-line/010543.html

4/5/2005

George Ticknor

Page 2 of 4

revelations, augmented by an Englishman's account of the

treasures in that university's library, convinced Ticknor to make

Göttingen his destination.

But before leaving for Europe, he broadened acquaintance with

his own country. Traveling south, he dined with President

Madison and journeyed to Monticello, where Thomas Jefferson

reflected on his own years in Europe and offered letters of

introduction to surviving friends in France. As a result, when

Ticknor did reach Paris, he was greeted as the newest

representative of the upstart American republic and what it

signified to European liberals. Mme. de Staël herself, though

seriously ill, was eager to see him and declared with animation

about the United States, "You are the vanguard of the human race,

you are the future of the world."

Twenty months at Göttingen, however, taught Ticknor something

different: in humane learning, America was well in the rear. He

found his Greek tutor, only two years his senior, far beyond him in

breadth and precision of knowledge. "What a mortifying distance

there is," he wrote his father, "between a European and an

American scholar. We do not yet know what a Greek scholar is; we

do not even know the process by which a man is to be made one."

Reflecting on his experience of German academic discipline,

Ticknor resolved to apply its methods at Harvard. For President

John Kirkland he wrote out a comprehensive plan for a full-scale

departmental program on the German model, including lectures

in the prescribed languages. When he found that the prevailing

conditions of instruction at the College stood in his way, he set

about promoting an across-the-board reform of the entire

academic program. "A great and thorough change must take place

in its discipline and instruction" to make sure, he added-with an

asperity not likely to endear him to colleagues-that the College

would at least "fulfill the purposes of a respectable high school."

President Kirkland

acknowledged the

need for reform

and was

sympathetic to

Ticknor's

proposals, but the

http://www.harvardmagazine.com/on-line/010543.html

4/5/2005

George Ticknor

Page 3 of 4

faculty at large was

not. "The resident

teachers," Ticknor

told a friend,

"declared

themselves against

all but very trifling

changes." The

Harvard he

envisioned and for

which he had

prepared himself

would begin to

materialize only

under President

Charles William

Eliot, a half-

century later.

Ticknor never

really settled into

A formal carte de visite photograph of Ticknor.

the still provincial

Such images were popular for publicity

Harvard

purposes and personal use.

community.

Photograph courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

Scrupulous about

his duties, he

offered courses on Dante and Shakespeare as well as on his

appointed French and Spanish subjects. (His services are

commemorated by Ticknor Lounge in Boylston Hall, the present

home of Romance language studies.) But he chose to reside in

Boston rather than Cambridge; his elegant townhouse at the

corner of Park and Beacon became the setting for a life closer to

that of a prosperous patrician than of a dry-as-dust pedagogue.

What he lived for, most of all, were his return visits to Europe. In

preparing his monumental History of Spanish Literature,

published in 1849, he assembled an extraordinary library of books

and documents, rescuing many from slow disintegration in

neglected archives and vaults. He maintained cordial relations

with scholars, intellectuals, and cultivated aristocrats in several

countries who shared his interests.

Although he resigned from Harvard in 1835 to concentrate on his

History, he remained hopeful about the College's future. Writing

http://www.harvardmagazine.com/on-line/010543.html

4/5/2005

George Ticknor

Page 4 of 4

in 1859 to the eminent British geologist Charles Lyell, he declared

that, with "the best law school in the country, one of the best

observatories in the world, a good medical school...[and] the

Lawrence Scientific School, [we can become] a true university,

and bring up the Greek, Latin, mathematics, history, philosophy,

etc., to their proper level. At least I hope so, and mean to work for

it."

Warner Berthoff is Cabot professor of English and American

literature emeritus.

More features.

Next..

January-February 2005: Volume 107, Number 3, Page 48

Copyright © 01996-2005 Harvard Magazine, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Home Class Notes I Classifieds I Back Issues Contact Us I Advertise Subscribe Donate

Search

I Report an Error

I

Contact the Webmaster

I

Staff Page

http://www.harvardmagazine.com/on-line/010543.html

4/5/2005

5/26/2016

Harvard Magazine

Your independent source for Harvard news since 1898

HARVAR

MAGAZINE

Log-In Register

Remaking the Mosquito

The of malaria

HARVARD

MAGAZINE

a Search

ARTICLES

CURRENT ISSUE

ARCHIVES

CLASS NOTES

CLASSIFIEDS

DONATE

YOUR SUPPORT

makes Harvard

DONATE

Magazine possible.

FEATURES

George Ticknor

Brief life of a scholarly pioneer: 1791-1871

by WARNER BERTHOFF

JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2005

B

y today's standards, Harvard College before the Civil War was a provincial

Commencement

academy, competent (judged Henry Adams) at preparing students to become

"respectable citizens," but effectively indifferent to the advances in knowledge

2016

Click Here to read our online

coverage sponsored by

beginning to shape the modern world. Yet one early member of its teaching faculty

the Harvard Alumni Card and

stands as a signal exception. George Ticknorinvited in 1816 to become Smith

the Harvard Alumni Association

professor of the French and Spanish languages and literaturesmay be called the first

Harvard scholar who would be warmly welcomed into the University faculty of 2005,

just as he was the first (outside the traditional fields of divinity and rhetoric) to hold a

On Readers' Radar

named chair in the humanities.

Not himself a graduate of the College, Ticknor had followed his father, a Boston merchant, to

1. Rashida Jones '97: "Don't Just Follow

Dartmouth in 1805, though of his two college years he remarked late in life, Ilearnt very

the Rules"

little." Back in Boston, his education began in earnest. He took up the serious study of Latin and

2. Sarah Jessica Parker Speaks at

Greek with the Reverend John Gardiner of Trinity Church and subsequently read for the law.

Harvard Law School Class Day 2016

But his heart remained in humane learning and, with his father's approval, he proposed to

consolidate his studies at a European university: with Napoleon's downfall in 1815, the

3. Live Life to Its Fullest, HBS Class Day

continent was once again open to American visitors. By then Ticknor had read with excitement

Speakers Urge

Mme. de Staèl's momentous book De l'Allemagne, with its report of dramatic advances in

4. Madeleine Albright Urges Graduates

German philosophy and literature, as well as a pamphlet describing the University of

to Look Beyond America's Borders

Göttingen's revolutionary system of study. These revelations, augmented by an Englishman's

account of the treasures in that university's library, convinced Ticknor to make Göttingen his

5. Harvard's 2016 Honorary-Degree

destination.

Recipients

But before leaving for Europe, he broadened acquaintance with his own country. Traveling

south, he dined with President Madison and journeyed to Monticello, where Thomas Jefferson

reflected on his own years in Europe and offered letters of introduction to surviving friends in

France. As a result, when Ticknor did reach Paris, he was greeted as the newest representative

of the upstart American republic and what it signified to European liberals. Mme. de Staël

herself, though seriously ill, was eager to see him and declared with animation about the United

States, "You are the vanguard of the human race, you are the future of the world."

Twenty months at Göttingen, however, taught Ticknor something different: in humane

http://harvardmagazine.com/2005/01/george-ticknor.html

1/3

5/26/2016

Harvard Magazine

learning, America was well in the rear. He found his Greek tutor, only two years his senior, far

beyond him in breadth and precision of knowledge. "What a mortifying distance there is," he

INVEST IN HARVARD

wrote his father, "between a European and an American scholar. We do not yet know what a

AND YOUR

Greek scholar is; we do not even know the process by which a man is to be made one."

FINANCIAL FUTURE

Reflecting on his experience of German academic discipline, Ticknor resolved to apply its

methods at Harvard. For President John Kirkland he wrote out a comprehensive plan for a full-

Learn more about planned gift strategies

scale departmental program on the German model, including lectures in the prescribed

languages. When he found that the prevailing conditions of instruction at the College stood in

HARVARD

UNIVERSITY PLANNED GIVING

his way, he set about promoting an across-the-board reform of the entire academic program. "A

great and thorough change must take place in its discipline and instruction" to make sure, he

addedwith an asperity not likely to endear him to colleaguesthat the College would at least

"fulfill the purposes of a respectable high school."

President Kirkland acknowledged the need

for reform and was sympathetic to Ticknor's

proposals, but the faculty at large was not.

"The resident teachers," Ticknor told a friend,

"declared themselves against all but very

trifling changes." The Harvard he envisioned

and for which he had prepared himself would

begin to materialize only under President

Charles William Eliot, a half-century later.

Ticknor never really settled into the still

provincial Harvard community. Scrupulous

about his duties, he offered courses on Dante

and Shakespeare as well as on his appointed

French and Spanish subjects. (His services are

commemorated by Ticknor Lounge in

Boylston Hall, the present home of Romance

language studies.) But he chose to reside in

Boston rather than Cambridge; his elegant

townhouse at the corner of Park and Beacon

A formal carte de visite photograph of Ticknor.

Such images were popular for publicity purposes

became the setting for a life closer to that of a

and personal use.

prosperous patrician than of a dry-as-dust

Photograph courtesy of the Harvard University pedagogue. What he lived for, most of

all,

Archives

were his return visits to Europe. In preparing

his monumental History of Spanish Literature,

published in 1849, he assembled an

extraordinary library of books and documents, rescuing many from slow disintegration in

neglected archives and vaults. He maintained cordial relations with scholars, intellectuals, and

cultivated aristocrats in several countries who shared his interests.

Although he resigned from Harvard in 1835 to concentrate on his History, he remained hopeful

about the College's future. Writing in 1859 to the eminent British geologist Charles Lyell, he

declared that, with "the best law school in the country, one of the best observatories in the

world, a good medical school...[and] the Lawrence Scientific School, [we can become] a true

university, and bring up the Greek, Latin, mathematics, history, philosophy, etc., to their

proper level. At least I hope so, and mean to work for it."

Warner Berthoff is Cabot professor of English and American literature emeritus.

http://harvardmagazine.com/2005/01/george-ticknor.html

2/3

Anna Ticknor Papers, 1835 - 1837: Full Finding Aid

Page 1 of 4

Manuscript MS-1249

SeriAnna isicknor Papers, 1835 - 1837

Box: 1. Dates: 1835-1837

Manuscript MS-1249

FULL FINDING AID

Title: Anna Ticknor Papers, 1835-1837 -

Call Number: Manuscript MS-1249

Collection Dates: 1835 - 1837

Size of Collection:

1 box (1.5 linear ft.)

Abstract: Anna Ticknor (1800-1885), wife of George Ticknor. The collection

consists of eight diaries of her travels through Europe with her

family from 1835-1837.

Note: Is there overlap-

Access to Collection: Unrestricted.

or interaction-between

USE & ACCESS

that of Sanual g. Ward ?

The materials represented in this guide may be accessed through the Rauner Special

Collections Library at Dartmouth College. Rauner Library is located in Webster Hall. The

materials must be used on-site and may not leave Rauner Library.

Rauner Special Collections Library is open to the public and in most cases no appointment is

necessary. The exception is in the case of materials stored off site for which there may be a

delay of up to 48 hours in retrieval. Please consult the Access to Collection statement below or

contact Rauner Reference.

Rauner Library Hours

Rauner Library Patron Information

ACCESS TO COLLECTION

Unrestricted.

USE RESTRICTIONS

Permission from Dartmouth College required for publication or reproduction.

https://ead.dartmouth.edu/html/ms1249_fullguide.html

4/27/2018

Anna Ticknor Papers, 1835 - 1837: Full Finding Aid

Page 2 of 4

Manuscript MS 124

INTRODUCTION TO THE COLLECTION

Ser Containsies glit the documenting Anna Ticknor's European travels from 1835-1837. The

Box: Dates: 1835-1837

diaries contain detailed descriptions of activities, including stagecoach rides, booksellers'

dinners, and visits to artists' galleries and factories. Anna's first diary begins on May 25th, 1835

and the eighth concludes on December 13, 1837. No detailed entries exist after this date,

though a rough outline of events from December 12, 1837 to January 3, 1838 includes the

names of friends who called, theaters they attended, and the arrival of letters.

BIOGRAPHY

Anna Ticknor was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts on September 23, 1800. Anna was the

daughter of wealthy Boston merchant, Samuel Eliot, and the wife of the American academic

and Hispanist, George Ticknor. The couple had four children, two of whom died in early

childhood. Anna died on February 14th, 1885 in Boston, Massachusetts.

Series, Box & Folder List

SERIES 1, DIARIES, 1835-1837

Europe, 1835-1837.

ACCESS RESTRICTIONS

Unrestricted.

BOX: 1, DATES: 1835-1837

ACCESS RESTRICTIONS

Unrestricted.

BOX CONTENTS

Folder: 1, Volume I, May - September 1835

Anna Ticknor describes how it feels to make a long sea voyage which nearly ends in

catastrophe. She gives her first impressions of Liverpool, Birmingham, and London.

She is horrified by examples of poverty and degradation, while enchanted by

examples of wealth and luxury. She meets Maria Edgeworth, Mary Russel Mitford,

the Wordsworths, and the Southeys.

Folder: 2, Volume II, September - November 1835

https://ead.dartmouth.edu/html/ms1249_fullguide.html

4/27/2018

Anna Ticknor Papers, 1835 - 1837: Full Finding Aid

Page 3 of 4

on daily life at several English country houses and long passages on

Series 1, Diaries, the 1835-1837 York Music Festival, the Doncaster races, Wentworth House, and the Fitzwilliam

Box: 1, Dates: fan5H1837

Folder: 3, Volume III, November 1835 - May 1836

Contains general impressions of the Continent, but also detailed and informative

accounts of life in Dresden, where the Ticknors resided during the winter of 1835-36.

Along with her husband Anna attends balls and befriends aristocrats and members of

the royal family, including the future king of Saxony. Anna provides descriptions of

scenes at court, as well as her response to works of art. The volume ends with her

comments on the journey from Dresden to Berlin.

Folder: 4, Volume IV, May - August 1836

Report on three cities - Berlin, Vienna, and Munich. In each, Anna visits museums,

galleries, and institutes. Among the highlights of this volume are Anna's first meeting

with Alexander von Humboldt; several dinners in different cities which allow her to

comment on various styles of formal entertainment; and visits to a large number of

churches and monasteries on the way from Vienna to Munich. Anna recalls a happy

stay at the castle of Count and Countess Thum of Howenstein.

Folder: 5, Volume V, August - December 1836

The family begins in Munich and ends in Rome. From Munich they go to Bern; they

travel through the Swiss Alps, enter Italy by way of the Simplon Road, spend a week

in Turin, a week in Milan, several days in quarantine at Castel Franco, and then

nearly a month in Florence. Anna tells a story of the ascent of Righi by horseback

and a nighttime storm at the summit, and rumors of cholera and the squalid condition

of people in various parts of northern Italy. In Milan, at the Scala, Anna is enchanted

by the opera, but puzzled at the ballet. The Ticknors continue to keep in touch with

important people, including the Grand Duke in Florence.

Folder: 6, Volume VI, December 1836 - March 1837

This volume is devoted almost exclusively to the Ticknor family's stay in Rome.

They arrived in early December, and stayed in spacious quarters on the Pincio. Mrs.

Ticknor's remarks are largely focused on the art world and cultural treasures she

found there. However, Anna was unenthusiastic about Roman society, especially

Italian female aristocrats.

Folder: 7, Volume VII, March - July 1837

https://ead.dartmouth.edu/html/ms1249_fullguide.html

4/27/2018

Anna Ticknor Papers, 1835 - 1837: Full Finding Aid

Page 4 of 4

Manuscript

Thestipknors head north toward Paris. This volume deals with their final months in

Series 1, Diaries, Rome 1835-1837 and the family's travels to Perugia, Florence, Genoa, Venice, and the

Box: 1, Dates: Alps. Anna Ticknor chronicles days filled with art and language lessons,

visits to museums and galleries, and tours of Rome. By the end of this journal, the

family visits La Spezia and travels along the mountains of Italy's north.

Folder: 8, Volume VIII, July - December 1837

In this volume of her journal, Anna Ticknor displays her interest with the Italian and

Swiss Alps, the Rhine River Valley, and the botanical gardens of Liège and Paris.

Her entries reveal her sharp eye for native costume, peasant crafts, and rural

architecture. At the Bellagio, near the Splugen Pass, she finds comfort in lounging

and drinking in the natural world around her.

https://ead.dartmouth.edu/html/ms1249_fullguide.html

4/27/2018

WIKIPEDIA

Anna Eliot Ticknor

Anna Eliot Ticknor (Boston, Massachusetts, June 1, 1823 - October 5, 1896) was an

American author and educator. In 1873, Ticknor founded the Society to Encourage Studies at

Home which was the first correspondence school in the United States. ¹ She is attributed as

being a pioneer of distance learning in the United States, and the mother of correspondence

schools. [2][3] She served as one of the original appointees to the Massachusetts Free Public

Library Commission,4 which was the first of its kind in the United States. [5]

Contents

Family

Author

The Society to Encourage Studies at Home

Death and legacy

References

Anna Eliot Ticknor

External links

Family

Anna Eliot Ticknor was the oldest child of George Ticknor and Anna (Eliot) Ticknor. She was

born on June 1, 1823. Her siblings were George Haven Ticknor, who died during his childhood at

age 5; Susan Perkins Ticknor, who died in infancy; and Eliza Sullivan (Ticknor) Dexter (1833

-1880). [6][7]

Her paternal grandfather was Elisha Ticknor who was the impetus for the system of free primary

schools in Boston, and one of the founders of the first savings bank, Provident Institution for

Savings in the Town of Boston, in the United States. [8] Her father was a Harvard University

professor. [1] Her mother was a writer. [1] Her maternal grandfather was Samuel Eliot, a Boston

merchant. Her mother's brother, Samuel A. Eliot was the treasuror of Harvard College. [6]

Author

In 1896, Ticknor wrote a children's book, An American Family in Paris: With Fifty-Eight

Illustrations of Historical Monuments and Familiar Scenes.

George Ticknor

The Society to Encourage Studies at Home

In Boston, Massachusetts in 1873, Ticknor founded an organization of women who taught

women students through the mail. 9 [[10] Her society was the first correspondence school in the

United States, and an early effort to offer higher education to women. ¹ [9] To assist the student in

obtaining the needed study materials, in 1875 a lending library was established. The collection

gradually grew to contain several thousand volumes. The purpose of the study varied between

the different students with some people being young women with minimal schooling and others

being educated women seeking an advanced learning opportunity.

Lending library in Ticknor's family

Death and legacy

residence.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Eliot_Ticknor

4/27/2018

Anna Ticknor died on October 5, 1896. [1] After her death, the Society to Encourage Studies at Home released a history of the organization as

a tribute to her. The book contains letters exchanged between Ticknor, students, and other people associated with the organization and

gives an overview of the workings of the Society and the impact that it had on its students. The Society ceased operating after her death, and

the Anna Ticknor Library Association was formed to circulate the former Society's books, photographs, and other materials to a larger

group of interest learners.11[[11]

References

1. Society to Encourage Studies at Home

https://openlibrary.org/books/OL23472361M/Society_to_Encourage_Studies_at_Home_Founded_in_1873_by_Anna_Eliot_Ticknor_...

Cambridge: Riverside Press. 1897. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

2. Holmberg, Börje (June 1995). "The Evolution of the Character and Practice of Distance Education" (http://www.c3l.uni-

oldenburg.de/cde/found/holmbg95.htm). Open Learning: 47-53. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

3. Bower, Beverly L.; Hardy, Kimberly P. (Winter 2004). "1". From Correspondence to Cyberspace: Changes and Challenges in Distance

Education(http://www.qou.edu/arabic/researchProgram/distanceLearning/changesChallenges.pdf)(PDF). Wiley Periodicals, Inc. pp. 5

-12. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

4. Massachusetts Librarian of the State Library, ed. (1897). Public documents of Massachusetts, Volume 8, Part 2

https://books.google.com/books?id=xdMWAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA1-PA7&dq=Anna+Eliot+Ticknor#v=onepage&q=Anna%20Eliot%

20Ticknor&f=false). Boston: Wright & Potter, State Printers. p. 7. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

5. Paula Watson. "Valleys without sunsets: women's clubs and traveling libraries." In: Robert S. Freeman, David M. Hovde, eds. Libraries

to the people: histories of outreach. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003

6. National Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations, Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations, Association

of Modern Language Teachers of the Central West and South, and National Federation of Modern Language Teachers. 1916. The

Modern language journal. Madison, Wis. [etc.]: National Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations.

7. Mott, Wesley T. 2001. The American Renaissance in New England Third series. Detroit: The Gale Group.

8. Lance Edwin Davis and Peter Lester Payne. From Benevolence to Business: The Story of Two Savings Banks. Business History

Review, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Winter, 1958), pp. 386-406.

9.

Bergmann, Harriet F. "The Silent University": The Society to Encourage Studies at Home, 1873-1897 in The New England Quarterly.

Boston: September 2001. Vol. 74 No. 3. pp 447-77

10. Good Housekeeping. 1885. New York, etc: s.n. pages 45, 70.

11. Abbott, Lyman, Hamilton Wright Mabie, Ernest Hamlin Abbott, and Francis Rufus Bellamy. 1893. The Outlook. New York: Outlook Co.

page 941

External links

The Ticknor Society (http://www.ticknor.org/index.htm#about)

Works by or about Anna Eliot Ticknor(https://archive.org/search.php?query=%28%28subject%3A%22Ticknor%2C%20Anna%

20Eliot%22%20OR%20subject%3A%22Ticknor%2C%20Anna%20E%2E%22%20OR%20subject%3A%22Ticknor%2C%20A%2E%

20E%2E%22%20OR%20subject%3A%22Anna%20Eliot%20Ticknor%22%200R%20subject%3A%22Anna%20E%2E%20Ticknor%

22%20OR%20subject%3A%22A%2E%20E%2E%20Ticknor%22%200R%20subject%3A%22Ticknor%2C%20Anna%22%20OR%

20subject%3A%22Anna%20Ticknor%22%20OR%20creator%3A%22Anna%20Eliot%20Ticknor%22%20OR%20creator%3A%

22Anna%20E%2E%20Ticknor%22%20OR%20creator%3A%22A%2E%20E%2E%20Ticknor%22%20OR%20creator%3A%22A%2E

20Eliot%20Ticknor%22%20OR%20creator%3A%22Ticknor%2C%20Anna%20Eliot%22%20OR%20creator%3A%22Ticknor%2C

20Anna%20E%2E%22%20OR%20creator%3A%22Ticknor%2C%20A%2E%20E%2E%22%20OR%20creator%3A%22Ticknor%2C%

20A%2E%20Eliot%22%20OR%20creator%3A%22Anna%20Ticknor%22%20OR%20creator%3A%22Ticknor%2C%20Anna%22%

2A%2E%20E%2E%20Ticknor%22%200R%20title%3A%22Anna%20Ticknor%22%20OR%20description%3A%22Anna%20Eliot%

20Ticknor%22%20OR%20description%3A%22Anna%20E%2E%20Ticknor%22%20OR%20description%3A%22A%2E%20E%2E%

20Ticknor%22%200R%20description%3A%22Ticknor%2C%20Anna%20Eliot%22%200R%20description%3A%22Ticknor%2C%

20Anna%20E%2E%22%20OR%20description%3A%22Anna%20Ticknor%22%20OR%20description%3A%22Ticknor%2C%20Ann

22%29%20OR%20%28%221823-1896%22%20AND%20Ticknor%29%29%20AND%20%28-mediatype:software%29)at Internet

Archive

Retrieved from "https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Anna_Eliot_Ticknor&oldid=798478787"

This page was last edited on 2 September 2017, at 06:01.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to

the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Eliot_Ticknor

4/27/2018

The Research Libraries of The New York Public Library /All Locations

Page 1 of 2

The New York Public Library

CATNYP: The Research Libraries Online Catalog

ACCESS Card My CATNYP Account Help

CATNYP Classes

Archives &

Manuscripts

LEO, The Branch Libraries' Catalog

Start Over

Save Record

Return to List

Another Search

(Search History)

AUTHOR

Ticknor, George, 1791-1871.

Entire Collection

Search

Record 35 of 37

Record: Prev Next

Call #

*Z-2978

Author

Ticknor, George, 1791-1871.

Title

The travel journals of George & Anna Ticknor in the years 1816-

1819 and 1835-1838.

Imprint

[v.p., 1816-1838]

URL for this record

LOCATION

CALL #

STATUS

Humanities- Microforms

*Z-2978

Division

Humanities- Microforms

Descript

26 V. illus.

Note

Microfilm by University Microfilms, 1974. 5 reels.

Original material at Dartmouth College Library.

Vol. 1 includes: A guide to the microfiche edition of the European

journals of George and Anna Ticknor, edited by Steven Allaback and

Alexander Medlicott. Hanover, N. H., Dartmouth College Library,

1978. vi, 101 p.

Subject

Europe -- Description and travel.

Add'l name

Ticknor, Anna Eliot, 1800-1885.

Allaback, Steven.

Medlicott, Alexander.

Dartmouth College. Library.

http://catnyp.nypl.org/search/aTicknor%2C+George%2C+1791-1871./aticknor+george+17.. 2/25/2007

6/4/2020

Remember Jamaica Plain?: 2009

Resources:

Followers (37) Next

Backhouse, Constance. "The Heiress versus the Establishment: The First

Female Litigator Before the Privy Council."

POSTED BY MARK B. AT 8:55 PM 1 COMMENT: LINKS TO THIS POST

a

A

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2009

William D. Ticknor - Publisher

HITCOUNTER

ANALYTICS

Offices of Ticknor and Fields (Old Corner Book Store).

William D. Ticknor was born in Lebanon

New Hampshire August 6, 1810 on the

family farm. In 1827 he left for Boston to

work in the brokerage house of his uncle

Benjamin. By 1832, he had partnered

with John Allen to form the publishing

company Allen and Ticknor, which was

housed in the now-famous Old Corner

Book Store building.

As partners came and went, the company named changed, with Ticknor and

Fields being perhaps the best remembered. From the Old Corner Book

Store, they published many of the leading literary lights of New England,

such as Emerson, Hawthorne, Thoreau, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., as well

Harriot Beecher Stowe and Horatio Alger At a time when

6/4/2020

Remember Jamaica Plain?: 2009

international copyright was not upheld, in 1842 they paid Alfred, Lord

Tennyson a royalty for publishing his work, an early act of fair play in a

business in which pirating of books was a common complaint on both sides

of the Atlantic. While at the Old Corner Book Store, they also published the

Atlantic Monthly. (For an extra credit nugget, I found a single sentence 1841

newspaper advertisement for De Quincey's Confessions of an Opium

Addict). Eventually, the outgrew the location and moved to Tremont street.

Over time, partners and name changes came and went, and the company

eventually became part of Houghton, Osgood and Company, which later

became Houghton Mifflin.

Burroughs street, 1874.

Ticknor house, Burroughs street.

In 1854, Ticknor bought land between Pond and Burroughs streets in

Jamaica Plain, and built a house on the Burroughs street side. We can

imagine friends like Hawthorne traveling out of the city and visiting the

6/4/2020

Remember Jamaica Plain?: 2009

speaking tour, Ticknor was his host, and perhaps he might have visited

3

Burroughs street as well.

[Note: I've just learned that Caroline Ticknor related a story of Dickens

visiting the Ticknor house in Jamaica Plain. After the great man left the

house, a shy relative followed him outside, and made a copy of the

impression his foot left in the soft gravel.]

In 1862, William Ticknor journeyed south to Washington D.C. with his

friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, where they met President Lincoln. In March

of 1864, they set out to Washington again, in hopes that the milder weather

would aid Hawthorne's poor health. During the trip, it was Ticknor's health

that took a turn for the worse, and he died at the Continental Hotel in

Philadelphia with his friend by his side. Hawthorne returned to Concord,

but in a month he would be dead as well.

Ticknor and his wife, Emeline Staniford Holt had five surviving children,

including three sons who went to Harvard. Howard Malcolm, Benjamin

Holt and Thomas Baldwin Ticknor all went into the business. Before joining

the firm, Benjamin first enlisted in the army during the Civil war, and at

one time was in charge of recruiting at the Readville training camp.

Howard Ticknor lived in the family house through at least the 1880s . The

1874 map above shows the house still owned by the estate of William D.

Ticknor. Son Benjamin stayed in Jamaica Plain as well, buying a lot on

Harris avenue from Captain Charles Brewer. The 1874 map shows

Benjamin H. Ticknor at 13 Harris avenue. Unlike his father's house,

Benjamin's home still stands today as number 15. The small, twentieth

century house that sits to the right of it was added to the same property,

and now carries the address 13A.

6/4/2020

Remember Jamaica Plain?: 2009

Harris avenue, 1874.

Benjamin's household was in interesting one. The 1880 census lists his wife,

Caroline daughters Caroline, aged 13, and Edith, aged 11, as well has sister

Elinor, aged 35 and brother Thomas, aged 30. To that, we can add four

female domestics and one coachman. Although only two of five servants

were Irish-born, two others had Irish parents, the other woman being from

Newfoundland. So four women to care for six people, including the woman

of the house. I think we can say that the Irish were nineteenth-century

Jamaica Plain's version of labor-saving devices.

Benjamin's daughter Caroline went on to have a career as a writer and

editor. She wrote Hawthorne and His Friend (the friend being her

grandfather William D. Ticknor), May Alcott, A Memoir, and Glimpses of

Authors (cited above), and edited Holmes's Boston, with Oliver Wendell

Holmes Jr., and numerous books. In 1925, Caroline and sister Edith were

still living at the house on Harris avenue

POSTED BY MARK B. AT 12:01 AM NO COMMENTS: LINKS TO THIS POST

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 24, 2009

Thanksgiving At The Zoo

Boston Daily Globe November 30, 1923

Animals in Zoo Given Thanksgiving Dinner

Codliver oil and garlic may not sound like the average person's idea of a real

Thanksgiving dinner, but they were two of the most popular dishes at the

Franklin Park Zoo yesterday. Deputy Park Commissioner William P. Long,

following the custom of some years, ordered a Thanksgiving dinner for the

birds and beasts at the Jamaica Plain institution, and last night every one

was happy, even Mutt, the hyena.

The codliver oil was for the two Polar bears Pasha and Fatima, and the big

beasts lapped the dishes dry and begged for more. As for the garlic it is

Tony's, the youngest elephant's idea of white meat and fixin's. Curiously

enough Waddy, the other elephant, will not touch garlic, but ate the regular

dinner of hay, bread and carrots with relish.

The other inmates received the "eats" which they love best. There was fruit

of various sorts for the monkeys, mutton for the brown, black and grizzly

bears, and SO on down the long list.

POSTED BY MARK B. AT 6:37 PM 2 COMMENTS: LINKS TO THIS POST

LABELS: FRANKLIN PARK, ZOO

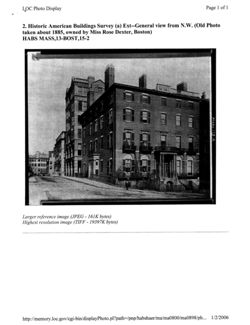

Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record

Page 1 of 2

Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record

(If noted, names of

Supplemental

delineators and date of

Material

creation are found on

drawings

b&w photos

data pages

the drawings.)

Amory-Ticknor House

9 Park Street, Boston, Suffolk County, MA

Drawings 1 through 6 of 20

NEXT GROUP

For a larger reference image, click on the picture or text.

Bibliographic information I Start Over in the Catalog

AMORY-TICKNOR - HOUSE

DOENER of PARK AND BACON STREETS

o C

Bibliographic information I Start Over in the Catalog

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=pphhsheet&fileName=ma/ma0800/ma0898/s

1/2/2006

MA0898

Page 1 of 2

P&P Online

Go to P&P

Catalog Start

NEW SEARCH HELP ABOUT COLLECTION

Reading Room

Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American

Landscapes Survey

Supplemental

Material

19 drawings

13 b&w photos

1 data pages

How to obtain copies of this item

TITLE:

Amory-Ticknor House, 9 Park Street, Boston, Suffolk County, MA

CALL NUMBER:

HABS MASS,13-BOST,15-

REPRODUCTION NUMBER:

[See Call Number]

MEDIUM:

Measured Drawing(s): 19 (18 X 24 in.)

Photo(s): 13 (8x 10 in.)

DATE:

Documentation compiled after 1933.

CREATOR:

Historic American Buildings Survey, creator

RELATED NAME(S):

Amory, Thomas

Gore, Gov. Christopher

Dexter, Samuel

Ticknor, George

NOTE:

Survey number HABS MA-175

Building/structure dates: 1804 initial construction

Building/structure dates: 1885 subsequent work

See also HABS MA-2-11-B for additional documentation.

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/S?pp/hh:@field(TITLE+@od1(Amory-Ticknor+House,... 1/2/2006

MA0898

Page 2 of 2

SUBJECTS:

MASSACHUSETTS--Suffolk County--Boston

COLLECTION:

Historic American Buildings Survey (Library of Congress)

REPOSITORY:

Library of Congress, Prints and Photograph Division, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

DIGID:

http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.ma0898

CONTENTS:

Photograph caption(s):

2. Historic American Buildings Survey (a) Ext--General view from N.W. (Old Photo taken about 1885,

owned by Miss Rose Dexter, Boston)

3. Historic American Buildings Survey, (Old Photo taken about 1885) owned by Miss Rose Dexter,

Boston (e) Ext-General view Part St. Front

4. Historic American Buildings Survey, Arthur C. Haskell, Photographer. 1935. (b) Ext- General View

from Northwest.

5. Historic American Buildings Survey, Arthur C. Haskell, Photographer. 1935. (c) Ext-View of West

Front, from Northwest.

6. Historic American Buildings Survey Arthur C. Haskell, Photographer October, 1934 (d) TICKNOR

HOUSE LAMP STANDARD AND RAILING FROM NORTHWEST

7. Historic American Buildings Survey, Arthur C. Haskell, Photographer. 1935. (d) Detail, Old Entrance

Porch. (West)

8. Historic American Buildings Survey Arthur C. Haskell, Photographer October, 1934 (e) DETAIL

VIEW OF TICKNOR HOUSE STANDARD AND STEPS FROM N.W.

9. Historic American Buildings Survey. Old Photo taken about 1885. (g) Int-Front Entrance from

Vestibule, 9 Park St. (Original owned by Miss Rose Dexter, Boston)

10. Historic American Buildings Survey. Old Photo taken about 1885. (f) Int-Front Staircase, Entrance

Hall, 9 Park St. (Original owned by Miss Rose Dexter, Boston)

11. Historic American Buildings Survey, (Old Photo taken about 1885.) (h) Int-Archway and Recess,

Rear Parlor, First Floor. (Original owned by Miss Rose Dexter, Boston)

12. Historic American Buildings Survey, (Old Photo taken about 1885) (j) View Library, South Side

Ticknor House, 2nd Floor. (Original owned by Miss Rose Dexter, Boston)

13. Historic American Buildings Survey. (Old Photo taken about 1885) (i) Int-Detail Library Mantel,

Ticknor House, 2nd Floor. (Original owned by Miss Rose Dexter, Boston)

14. Historic American Buildings Survey. (Old Photo taken about 1885) (k) Int-Mantel, Mrs. Ticknor's

Room, 2nd Floor. (Original owned by Miss Rose Dexter, Boston)

CARD #:

MA0898

P&P Online

Go to P&P

NEW SEARCH

HELP

ABOUT COLLECTION

Catalog Start

Reading Room

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/S?pp/hh:@field(TITLE+@od1(Amory-Ticknor+House,...

1/2/2006

Page 1 of 1

Photo

N.W.

Display

LOC

Boston)

by

Miss

3

2.

Historic

1885,

owned

taken

HABS

161K

bytes)

-

19397K

bytes)

1/2/2006

PS

1881

A4

LETTERS OF

any

1881

1910

144

1910

V. . .

HAWTHORNE

TO WILLIAM D. TICKNOR

1851-1864 /

Hartherne, 1804-1864

260636

VOLUME

I

2

UN 30 1970

NEWARK NEW JERSEY

Copyright, 1910, by THE CARTERET BOOK CLUB

THE CARTERET BOOK CLUB

1910

C

CLA268380

HARVARD

REMINISCENCES

BY

ANDREW P. PEABODY, D.D., LL.D.

PREACHER TO THE UNIVERSITY, AND PLUMMER PROFESSOR OF CHRISTIAN

MORALS, EMERITUS

BOSTON

TICKNOR AND COMPANY

211, Tremont Street

1888

iv

PREFACE.

which embrace fifty-six years of college-age, from

1776 to 1831 (inclusive).

To these biographical notices, I have appended

a chapter containing some of my reminiscences of

CONTENTS.

Harvard College as it was during my novitiate as

a student.

PAGE

AARON DEXTER

1

HENRY WARE

2

ISAAC PARKER

8

JOHN THORNTON KIRKLAND

9

STEPHEN H1GGINSON

17

JOSIAH QUINCY

20

LEVI HEDGE

37

JOHN SNELLING POPKIN

40

FRANCIS SALES

47

JAMES JACKSON

50

ASAHEL STEARNS

51

JOHN COLLINS WARREN

54

JOSEPH STORY

56

SIDNEY WILLARD

60

JOHN GORHAM

67

BENJAMIN PEIRCE

68

CHARLES SANDERS

68

JOHN FARRAR

70

ANDREWS NORTON

73

JACOB BIGELOW

79

THOMAS NUTTALL

80

GEORGE TICKNOR

81

WALTER CHANNING

83

EDWARD TYRREL CHANNING

84

JONATHAN BARBER

90

EDWARD EVERETT

91

JOHN WHITE WEBSTER

97

HENRY WARE

97

CHARLES FOLSOM

100

JOHN WARE.

104

THADDEUS WILLIAM HARRIS

105

V

vi

CONTENTS.

PAGE

GEORGE OTIS

106

JOHN GORHAM PALFREY

107

PIETRO BACHI

115

CHARLES FOLLEN

116

CHARLES BECK

124

FRANCIS MARIA JOSEPH SURAULT

126

OLIVER SPARHAWK

128

JOHN HOOKER ASHMUN

128

HARVARD REMINISCENCES.

JOHN FESSENDEN

129

GEORGE RAPALL NOYES

130

WILLIAM FARMER

134

JAMES HAYWARD

135

JOHN PORTER

138

AARON DEXTER.

NATHANIEL GAGE

138

(1776.)

WILLIAM PARSONS LUNT

139

GEORGE RIPLEY

140

THIS was the only name on the catalogue in my

BENJAMIN BRIGHAM

141

SAMUEL KIRKLAND LOTHROP

143

college days that bore the then rare and almost mys-

ALLEN PUTNAM

145

terious title of Emeritus, which Dr. Dexter retained

JOHN LANGDON SIBLEY.

146

ALANSON BRIGHAM

for thirteen years, after having filled the chair of

154

HERSEY BRADFORD GOODWIN

155

Chemistry and Materia Medica for thirty-three years.

GEORGE WASHINGTON HOSMER

157

In his time chemistry was almost an unknown terri-

GEORGE PUTNAM

159

OLIVER STEARNS

163

tory, while the field of materia medica was immeas-

EDMUND CUSHING

167

urably large; drugs and called) specifics having

CORNELIUS CONWAY FELTON

168

SETH SWEETSER

been not only in more ample use, but employed in a

176

GEORGE STILLMAN HILLARD

177

very much greater variety, than in the practice of

HENRY SWASEY MCKEAN

178

the present day. Dr. Dexter was chosen to office

JAMES FREEMAN CLARKE.

178

BENJAMIN ROBBINS CURTIS

179

in 1783, - the year after the formation of the Medi-

SAMUEL ADAMS DEVENS

179

cal School. His professorship was unendowed until

JOEL GILES

179

1790, when William Erving, moved by affection for

BENJAMIN PEIRCE

180

CHANDLER ROBBINS

187

Dr. Dexter, his physician and friend, left a thousand

THOMAS HOPKINSON

192

pounds, the income thereof to be applied to the

CHARLES EAMES

194

SUPPLEMENTARY CHAPTER

196

increase of the salary of the Professor of Chemistry.

Hence the name of the Erving Professorship now

held by Professor Cooke. In 1816 Dr. Dexter ten-

1

80

HARVARD REMINISCENCES.

GEORGE TICKNOR.

81

the high classical culture which, in his latter years,

struction by him to those who wanted it: but I never

Dr. Bigelow was wont to depreciate. He lingered to

heard of his having a pupil. Some of us had acquired

a late old age, wise, genial, and kind, beloved and

a working knowledge of the Linnman system, and

admired, with loss of sight, but with no failure in the

with the aid of Bigelow's Flora Bostoniensis" gath-

keenness of his mental vision; and the only sugges

ered and identified plants in the then flower-rich

tion of second childhood that he gave his friends was

region of alternating swamp and woodland on what

his doubling upon his track as to the classic tongues,

is now Kirkland Street; and we had heard a rumor

returning to the nursery, and making translations

of Jussicu's Natural Orders as an obtrusive inno-

from Mother Goose into Greek lyrics of classic dic-

vation on classes and orders that seemed to us too

tion, faultless prosody, and melodious rlyythm.

fundamentally "natural to be ever set aside. Mr.

Nuttall published several works of the highest merit,

THOMAS NUTTALIA

-treatises on botany and geology, "A Manual of

(Hon. A. M. 1826.)

the Ornithology of North America," and records of

DRAKE, in his 'Dictionary of American Biogra-

scientific travel in California and in the Mississippi

phy," substituting what ought to have been for what

Valley. Nn Englishman by birth, a printer by edu-

was, says that Mr. Nuttall was Professor of Botany

cation, he returned to England to take possession

and Natural History from 1822 to 1834. In point

of an estate devised to him on condition that he

of fact, on the death of Professor Peck, in 1822, the

should live upon it.

college found itself, and remained for twenty years,

too poor to maintain a professorship in this depart-

GEORGE TICKNOR.

ment. Mr. Quincy, in his "History," says that Mr.

(Dartmouth, 1807.)

Nuttall was appointed Curator of the Botanical

My readers well know how eminent a place Mr.

Garden in 1822. In the Triennial Catalogue the ap-

Ticknor filled in the world of letters and in society.

pointment is said to have been made in 1825. His

With a grace of address and manners commensurate

name was mythical to the members of college. We

with his elegant culture, with conversational gifts

used to hear of him as the greatest of naturalists;

equally ample and versatile, and with the prestige

but I never knew of his being seen. He lived in

the house belonging to the Botanic Garden, in a

1 The Azalea viscosa used to grow there in such profusion as, in

its season, to pervade that entire quarter of the town with its

then remote quarter of the town, which we seldom

fragrance. The Linnaea borealis, which has but few localities in New

explored. I think that the catalogue promised in-

England, used to be found there.

82

HARVARD REMINISCENCES

WALTER CHANNING.

83

of a reputation early won, and still earlier deserved,

might have had an audience more fully conversant

he was the first of the three men of cosmopolitan

with the literatures of which he was master.

fame that have filled the Smith Professorship of the

Mr. Ticknor deserves special commemoration for

French and Spanish Literature and of Belles-Lettres,

his services in the promotion of liberal culture and

his only successors having been his friends, Long-

the advancement of knowledge. II was chief among

fellow and Lowell. There is no need of my giving

the founders of the Boston Public Library. Still

a sketch of his life, for his Memoir has been gener-

more, he was generous as to the use of his own

ally read; and I must confine myself for the most

library, which, in all departments stocked with the

part to personal reminiscences. I doubt whether he

best authors in the best editions, was in his own

ever did any class-work : he certainly did not while

department the richest and most valuable in the

I was in college. But he delivered, in alternate

country. IIc never refused to lend a book, however

years, courses of lectures on French and on Spanish

precious; and his loans were SO frequent as to require

Literature, the last of these forming the substance

special registration as a guaranty against loss. I

of the first edition of his great work, the 'History

remember, that, when a young fellow-tutor of mine,

of Spanish Literature." These lectures had all the

not particularly intimate with him, wanted to write

qualities of style and method which fitted them for

a lecture on the "Ireland Forgeries," Mr. Ticknor

an academic audience. We knew that they were of

lent him the entire set of publications relating to

transcendent worth, and we listened to them cagerly

them, probably the only set in the country, and con-

and attentively. They were appreciated as highly,

sisting in part of facsimiles and privately printed

yet not SO intelligently, as they would have been a

monographs, which could not have been replaced.

few years later. They covered, for the most part,

I knew not a few instances of similar kindness,

a then unknown territory. Spanish literature was

indicating, no doubt, a broader charity than large

known mainly by translations of the few world-

pecuniary gifts would have implied.

famous authors; and, though the capacity of reading

French was not rare, there were very few French

WALTER CHANNING.

books to be had, and those few, the works of the

(1808.)

great writers of the seventeenth and eighteenth cen-

DR. WALTER CHANNING filled for about forty

turies, not the current literature of the time. But

years an important professorship in the Medical

Mr. Ticknor did much toward awakening curiosity,

School, and survived his graduation no less than

and creating the condition of things in which he

sixty-eight years. He had no connection with the

A COLLECTION ANALYSIS OF THE TICKNOR AND FIELDS COLLECTION

OF THE RARE BOOK COLLECTION

AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL

by

Ronald Laven Leach

A Master's paper submitted to the faculty

of the School of Information and Library Science

of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of Master of Science in

Library Science.

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

April, 2004

Approved by:

Charles B. McNamara

1

Table of Contents

Introduction

p. 2-4

Collection Analysis Project-Principles

p. 5-7

Methodology

p. 7-12

Historical Overview of Ticknor and Fields

p. 12-18

Collection Analysis Process

p. 18-20

Results and Findings

p. 20-32

Desiderata List-Principles

p. 33-34

Desiderata List

p. 35-41

Bibliography

p. 42-43

Ronald L. Leach. A Collection Analysis of the Ticknor and Fields Collection of the

Rare Book Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. A

Master's paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. April, 2004. 45 pages. Advisor: Charles

B. McNamara

This study is an analysis of the Rare Book Collection's holdings and desiderata list

for the Ticknor and Fields' collection and historical overview of the Ticknor and

Fields publishing house. The purpose of this collection analysis is to assist the

curator in collection development, to serve as a guide to researchers using the

collection, and to assist librarians and catalogers who will continue to describe,

catalog, and arrange the collection. This study is limited primarily to publications

issued by Ticknor and Fields during the period of 1849 to 1853.

The paper contains information on methodology and results and findings. It

contains an overview of high spots of the collection and list of desirable first

editions and selected later editions of items not currently in the Ticknor and Fields

collection of the Rare Book Collection.

Headings:

Ticknor & Fields

Collection development/College and university libraries--Rare books

Publishers and Publishing/History

2

Introduction

In 1987 the Rare Book Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel

Hill (RBC) acquired a collection of books and other materials emanating from one of the

premier publishing houses operating in mid-nineteenth century America--namely, the

house known as Ticknor and Fields. 1 This was no ordinary collection from the

publisher's archives; it was rather the result of a lifetime of book collecting by John

William Pye, who, after starting collecting books while a student in college, found that

"the name of Ticknor, Reed, and Fields [had] cast a spell on me." He goes on to describe

his self-guided mission as follows:

After several years of being hopelessly engulfed in the pursuit of

old books, I decided to specialize in the collecting of everything

that had been published by the Boston firm of Ticknor and Fields,

and their predecessors. This has been no small task, for besides

publishing the majority of work of [Longfellow, Lowell, Emerson,

Hawthorne and Whittier] the firm also published Henry David

Thoreau, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Julia Ward Howe [of the Battle

Hymn to the Republic fame], Oliver Wendell Holmes, Alfred Lord

Tennyson, Charles Kingsley, Charles Dickens, Robert Browning,

and Bert Harte. And these are only the well-known authors; my

collection includes the likes of Forsythe Wilson, Jonathan Barrett,

Mary Bartol Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, and Theodore Winthrop.

2

As a result of Pye's collecting efforts, the RBC acquired approximately 7,850

volumes (based upon the estimate of the RBC cataloger who processed and cataloged the

1 As will be discussed later, Ticknor and Fields, which began its existence in 1832 as Allen & Ticknor,

went through seven name changes over the course of its existence; for purposes of this paper the firm will

be primarily referred to as Ticknor and Fields, the name most commonly associated with the firm.

2 John W. Pye, The 100 Most Significant Books by Ticknor and Fields, 1832-1871: A Guidebook for

Collectors (Brockton : John William Pye Rare Books, 1995) 3.

3

collection) consisting of approximately 2,600 titles, 190 pieces of ephemera (letters,

manuscripts, broadsides, advertisements, royalty checks) and 54 bound volumes of

periodicals (including the renowned Atlantic Monthly series, which Ticknor and Fields

acquired in 1858 for the apparently bargain price of $10,000, for Fields had submitted

this bid for $10,000 expecting it to be rejected as too low). Another 200 transfers from

Davis Library enhanced RBC's Ticknor and Fields collection.

The RBC did not just acquire nearly the entire output of a representative

nineteenth-century American publishing house. For the publishing house of Ticknor and

Fields has been characterized in fact as "the most prestigious literary house in the United

States during the mid-nineteenth century"3; or in the words of the indefatigable scholar of

the Ticknor and Fields house, Michael Winship, "the preeminent publisher of belles-

letters, especially poetry, in the United States of the mid-nineteenth century

,,4

The RBC therefore has a veritable American treasure trove with its Ticknor and

Fields collection. It has received prominence in part through a Hanes Lecture delivered

by the afore-mentioned Ticknor and Fields scholar, Michael Winship, in which he

examined the business practices of the firm. 5 And with the increasing interest in the

study of the history of the book in American society and culture, especially the study of

literacy and of the book as a cultural and tangible object, along with book publishing

history in general, the thoroughness and comprehensiveness of the RBC's Ticknor and

3 Jeffrey Groves, "Judging Literary Books by their Covers: House Styles, Ticknor and Fields, and Literary

Promotion," in Reading Books: Essays on the Material Text and Literature in America, eds. Michele

Moylan and Lane Stiles (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996) 77.

Michael Winship, American Literary Publishing in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge

UP, 1995) 7.

5

Winship, Ticknor and Fields: The Business of Literary Publishing in the United States of the Nineteenth

Century (Chapel Hill: Rare Book Collection/University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel

Hill, 1992).

4

Field's collection should serve as a major source for research into the reading habits,

audiences, and interests (whether popular, juvenile, literary, political, religious,

intellectual, all genres or modes of thought represented by the books published by the

firm).

In an article entitled "Publishing in America," Winship asserts the untapped need

to pursue research in the subject of publishing history in America; in particular, to

discover and identify publisher's lists in advertisements, catalogues, and records and

thereby compile imprint lists to use for further research into book history. "We must,"

Winship notes, "complete the work of establishing the record of the published output of

the American book trade for our period This work will also involve discovering and

identifying publications that have not yet been recorded or described but, are listed in

publishers' advertisements, catalogues, and records.' ,,6 In view of the wealth of

advertisements inserted in many of the volumes published by Ticknor and Fields from as

early as the late 1830s with their often effusive praises lavished on the books, the RBC's

collection offers the willing researcher a bountiful primary source "to interpret how the

published output reacted to or affected a whole range of intellectual, political and cultural

movements.' ,,7 (emphasis added) And fortunately for the researcher the Ticknor and

Fields collection is thoroughly cataloged with four shelf list drawers in call number order

and in the online catalog at the RBC in main entry order.

6 Winship, "Publishing in America," in Needs and Opportunities in the History of the Book: America,

1639-1876, eds. David D. Hall and John B. Hench (Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1987) 96.

7

Ibid., 97.

5

Collection Analysis Project-Principles

Once a major collection such as the Ticknor and Fields collection has been

acquired by a library, it becomes essential in time to appraise the collection from the

standpoint of its completeness, potential deficiencies, its "high spots," and other key

elements of the collection. As a result of such analysis the current state of the collection

can be determined and attention given to filling the holes, assessing what materials are

present that may, in light of changing or evolving research interests, deserve special

emphasis and promotion in scholarly literature and other promotional sites, such as the

RBC's web site, SO as to communicate the mine of sources available for its exploitation

by interested scholars.

Ultimately, collection analysis assists the librarian or curator who needs to be

apprised of the lineaments of the collection in his or her constant effort to provide access

to the collection through collection development and cataloguing. Though, as intimated

SO far, the Ticknor and Fields' collection at the RBC is as nearly comprehensive a

collection as can be gathered in one institution, there are a few gaps in the collection

whose remedying will thereby improve the comprehensiveness of the collection and its

value as a source for the study of the history of the book and book culture in mid-

nineteenth century America.

Roderick Cave in his book, Rare Book Librarianship, sets out his view of

collection analysis as one of the principal methods for pursuing collection development in

a special collections arena:

A collection can be built up in [a] haphazard way provided time is

not of importance and the material is not also being sought by

other libraries or collectors, but a purposeful and coherent

acquisitions policy will demand that other methods also be

6

employed. At the core of this policy must lie the desiderata list,

the record of those books which the institution knows it needs for

the systematic development of the collection. The list will be built

up in a number of ways, of which the principal will be the

examination of the present collection by the rare books librarian

and other experts in the subject field This review will be

undertaken in terms of the general policy for its growth, to reveal

those key books and editions. which are not yet in its stock, and

are necessary to round it out. 8 (emphasis added)

Cave pertinently focuses on the construction of a desiderata list--the record of

those books or other materials needed for the comprehensive development of the

collection as a key element of the library's acquisitions policies. Where the desired goal

of acquiring a collection is to acquire, ideally, the entire output of an author or in this

case, the entire output of a major publishing house, the desiderata list becomes a central

tool in assisting the curator to meet that goal. Such lists should identify in descending

order the "musts" or "vitals" worthy of acquiring at any price, those items that are very

desirable if the price is "right" and those useful items where monies are readily available

such as unspent monies at the end of a budget year. These lists will then be furnished to

appropriate book dealers to search on behalf of the library, or in the current Internet era,

such lists can be used by in-house librarians charged with acquisitions to search directly

the preeminent online rare book dealers' web sites, such as Abebooks.com,

Bookfinder.com, or the Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America's (ABAA) web

site, to name just a few. These online dealers enable the librarian to truly search the

globe as web sites like Abebooks and Bookfinder are similar to electronic-based

bibliographic utilities like OCLC by bringing together the catalogs or records of dealers

from around the world into one searchable source--a major advancement in book

8 Roderick Cave, Rare Book Librarianship, Second rev.ed (London: Clive Bingley, 1992) 53.

10

number of the particular edition. Below the heading are recorded the date, details and

cost of paper, composition, printing, binding, royalty payments (denominated as

"copyright" or just "copr" in the Cost Books), and other illustrative details as appropriate.

Finally the date of publication and production cost per copy are noted along with trade

and retail prices (thus revealing the discount offered to the retailer).

A typical example of a Cost Book entry is the entry for The Scarlet Letter

(A173a) reproduced as follows:

[A173a]

1850

2500

The Scarlet Letter

2500

By Nathl Hawthorne

16 Mo. 324 pps. Metcalf & Co.

57 4/20 Reams. 18 1/2 X 29. 33.

4.75

268.30

320.586 ms. [ems]

@

43cents

130 11

115 Tokens.

75.

86 75

Ext Corrections

9 50

Copt. on 2400

@

15%

270 00

Binding

10

250 00

Cost Sheets 32.

clo 42.

Trade 75 1/4[discount]

Published Mar. 1850.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel, The scarlet letter, a romance

1 vol. 16mo [iii]-iv,322pp. Copyrighted by N. Hawthorne, 1850. Ticknor, Reed and

Fields, 1850.

The right-side figure of "2500" refers to the total number of volumes in an edition; the

left-side figure of "2500" refers to the total number of sets in an edition. The two would

differ only when the title is in two or more volumes. Metcalf & Co., printers to the

University [Harvard], became a staple printer for Ticknor and Fields during the period

from 1845-1858. The paper line refers first to the quantity (57 reams) used for the

printing, the size of the paper (18 1/2 x 29), pounds per ream (33), cents per lb. (4.75) and

11

extended costs for the quantity of reams used. The "ems" line identifies the number of

ems used in setting up the book for type, which number when multiplied by the cents per

em, gives the $130.11 total recorded above. The editors of the Cost Books note that the

presence or absence of the ems entry is significant as it may indicate that type was set up

anew for a particular edition of a book. For the second edition of The Scarlet Letter

(A179a) shows 303.930 ems, which reflects a different quantity from that used in

composing the A173a copy set out above, even though the first edition was published

only a month before the second. The reference to "Tokens" relates to the presswork; a

token was 500 impressions from one form; and the product of the 115 tokens figure and

75 cents yields the $86.75 total. The term "Copt" or "copyright" was used for what today

would be deemed royalties paid to the author; in this case paid only on 2400 of the 2500

copies printed, as the 100 copies for which royalties were not paid may have been review

copies or extra copies provided to the author as royalties were paid only on copies

actually sold. The cost of the binding for this edition can easily be computed by

multiplying 2500 for the number of copies printed by the $10 figure to arrive at the $250

figure. Finally, it appears from the Trade Cost information that 25% discount was

offered on a 75 cent trade price.

The editors give a concise summary of the published record of the Ticknor and

Fields house for the period of 1832 through 1858 covered by both Cost Books A that

bears repeating: For the period covered by Cost Books A and B, approximately 550 new

titles and 760 new editions were recorded; five new titles published under a double

imprint and one such new edition are also recorded. The total number of new titles and

new editions equals about 1,316 items. Additionally, the editors supplied 125 new titles

12

and 33 new titles with a double imprint from titles omitted from the Cost Books that the

editors were able to nonetheless provide, for an additional total of 158 books. In sum, for

the new titles and editions listed and those not listed but supplied by the editors, the grand

total is about 1,474. And based upon running totals throughout the Cost Books relating

to the number of volumes issued up to March 1854 the editors were able to compute a

total number of volumes issued from 1832 to 1854 of 996,394 and the cost of publishing

those volumes to be $205,027.61. These are fascinating details which the editors were

able to reconstitute especially as they reveal the strengths and extent of reach of one of

the great publishing houses in mid-nineteenth century America.