Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Search

results in pages

Metadata

COA Catalog 1973-1974

College of the Atlantic

Much as we would like to, we can no longer prepare students for life in

"tomorrow's world." We can barely conceive of tomorrow's world. With the

increasing pace of social and technological change, we can hope only to pre-

pare students to recognize the nature of change and to acquire the skills and

attitudes which will enable them to deal courageously and responsibly with the

problems associated with change.

An examination of ecological problems - - the interrelationship of man and

environment - has been chosen as the core of the curriculum not only be-

cause of the urgency of these problems (which makes them "relevant" in the

narrow sense), but because their very complexities provide the means for

developing habits of thought, action and feeling necessary for coping with a

changing world.

Problems in human ecology require perspectives difficult to acquire within

the confines of traditional academic and professional specialization. Parts

need to be continually related to wholes. Analysis and synthesis become alter-

nating emphases in a single continuing learning experience. The aim of this

kind of education is not the acquisition of a particular body of knowledge by

itself, but - as Alfred North Whitehead expressed it - "the acquisition of the

art of utilization of knowledge."

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC BAR HARBOR, MAINE.04609 (207) 288-5015

ACADEMIC CALENDAR, 1973-74

Saturday and Sunday, Sept. 15 & 16

Registration

Monday, Sept. 17

Classes begin

Friday, Nov. 30

First term ends

Wednesday, Jan. 2

Classes resume

Friday, March 8

Second term ends

Monday, March 25

Classes resume

Friday, May 31

End of third term

All new students are expected to spend three consecutive terms in resi-

dence. Thereafter, students who began in 1973 may spend two, three, or

four terms in residence per 12-month period.

The period from Monday, December 3, to Friday, December 14, will be de-

voted to a comprehensive evaluation of the first term's accomplishments.

Note: information regarding the 1973 outdoor orientation program and the

1974 summer term will be available shortly.

2.

CONTENTS

ACADEMIC CALENDAR

page 2

INTRODUCTION

page 5

MOUNT DESERT ISLAND

page 6

THE COLLEGE COMMUNITY

pages 8-10

Living Together; The Campus;

Housing; Cars; Health; In-

formal Curriculum; Special

Supplies

ARTS, CRAFTS AND ACTIVITIES

page 12

GOVERANCE

pages 14 & 15

ADMISSION AND FINANCIAL

AID

pages 16-19

Admission Policy and Proced-

ures; Transfer Students;

Financial Aid; College Costs

and Policies

EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM

pages 20-25

3.

Advising; Degree Require-

ments; Contract System;

Independent Study; Intern

Program

1973-74 CURRICULUM

page 26

FACULTY AND STAFF pages 48-49

TRUSTEES

page 50

II

INTRODUCTION

College of the Atlantic is a small, private, co-educational institution

awarding the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Human Ecology. The college pro-

vides an education which is both broadly based and carefully focussed. Rather

than sampling from a random assortment of disciplines, students participate in

an integrated curriculum organized around a central theme, the study of Human

Ecology.

The college began as a community effort, sponsored and organized by a

group of concerned Mount Desert Island residents who wished to bring in-

5.

creased intellectual diversity, environmental awareness, and economic stability

to the island. After four years of planning, the college opened in September

1972 with 32 students and 6 faculty members (4 full-time; 2 part-time).

The college's purpose is to study the various relationships which exist

between humans and their environment, including both the natural world which

supports our existence and the society and institutions which we have

created. Some of the clearest examples of this interaction are in the area

where people have done or threaten to do harm, both physical and aesthetic,

to the natural world. Concern with current and developing problems, matched

by an awareness of the forces of change, underlies the flexibility of the col-

lege's programs and the possibility for redefinition and modification which

exists at all levels of the college's operation.

The problem-centered curriculum is designed to utilize the thought and

research generated by both empirical and theoretical investigation. Offerings

include detailed examinations of specific environmental problems, supple-

mented by seminars covering a wide variety of related subject matter. The

curriculum itself may be regarded as a working system in which all the parts

complement and reinforce one another. There is no rigid department structure,

and persons with different backgrounds, disciplines, and experience work to-

gether. Some administrators teach; some faculty members share administra-

tive responsibilities. All members of the college community - students, staff,

and trustees — share the responsibility for implementing the college's goals.

2

MAINE

BANGOR

1

95

MT. DESERT

ISLAND

PORTLAND

College of the Atlantic

95

BOSTON

6.

HARDW

ISLAN

MOUNT DESERT ISLAND

Mount Desert Island is a uniquely beautiful combination of forests, lakes,

mountains, and ocean, about 250 miles "downeast" from Boston. Connected

to the mainland by a small bridge, the island has approximately 80 miles of

coastline and an area of 150 square miles. Portions of the island remain un-

developed; approximately one-third is permanently protected by Acadia Na-

tional Park.

During the period from October to June, the island is uncrowded and

quiet. The year-round population is about 8,000, largely concentrated in four

towns. In the summer, the residential population doubles, and more than two

million visitors flock to Bar Harbor to visit the park. The island's economy is

dominated in the summer by the tourist trade, and in the winter by boat-

building, fishing and lobstering, and the Jackson Laboratory, the nation's

largest center for the study of mammalian genetics.

With its glacial lakes, climax forests, scars of the 1947 fire, mountains,

and the ever-changing interface between land and sea, the island is an outdoor

laboratory of vast scope and resources. The impact of more than 2 million

tourists on the island's natural resources, economy, and collective psyche

offers opportunity for study (both theoretical and practical) in economics, law,

political decision-making, psychology, biology and aesthetics.

EASTERN BAY

THOMPSON NARROWS

ISLAND

DESERT

MT.

HULLS COVE

BAR ISLAND

WESTERN BAY

BAR HARBOR

BALD

PORCUPINE

ISLAND

annos SOMES

PRETTY HARBOR

SAND BEACH

HARDWOOD

ISLAND

BLACKWOODS

NORTHEAST HARBOR

GREENING

ISLAND

SUTTON ISLAND

SOUTHWEST HARBOR

BLUE HILL BLUE HILL BAY

LITTLE CRANBERRY ISLAND

SEAWALL

BASS

GREAT CRANBERRY ISLAND

BAKER ISLAND

HARBOR

BASS HARBOR LIGHT

THE COLLEGE COMMUNITY

The Campus

The campus is located in Bar Harbor on twenty-one acres of land with

eleven hundred feet of shoreline on Frenchman's Bay. It is bordered on the

north and south by summer residences, and on the west by State Route 3.

Route 3 leads directly into the town of Bar Harbor, less than a mile away to

the south.

There are four buildings which house all classrooms, laboratories, offices,

library, dining area, kitchens, and recreational space. Facilities include a dark-

room, student lounge, and several multiple use areas.

The library, consisting of approximately 5000 volumes and periodicals, is

supplemented by the MDI Environmental Resource Center.

In developing laboratory facilities, the college has received assistance and

encouragement from the Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor.

In addition to the shorefront property which it leases, the college owns

80 acres on Strawberry Hill, overlooking the town of Bar Harbor and French-

man's Bay. Initial planning for the development of the Strawberry Hill campus

has been underway for some time; students and faculty members have been

consulting regularly with the college's architect on the initial campus master

plan.

8.

Living Together

College of the Atlantic encourages its students to develop the capacity

for thoughtful and responsible self-direction. The principles of social free-

dom rest upon a basis of individual responsibility, for one's own actions and

for the general welfare of the college community.

The college also respects the laws and customs of the larger com-

munity, and is responsible for informing students of those laws and customs.

A college of human ecology cannot be an isolated academic enclave; the dis-

tinction betwen "college" and "outside world" will be reduced as much as

possible. College of the Atlantic began as a community effort, and remains an

integrated part of the community within which it grew.

Housing

There is no student housing on the college's present campus. Students

may either live in a motel dormitory near the college, or secure their own

lodgings in Bar Harbor or elsewhere on the island.

The motel is within easy walking distance of the campus, with a view

across Frenchman's Bay. Double rooms, with weekly laundry service and room

cleaning, cost $350 per person for the academic year. Single occupancy costs

$500. Students living in the motel dorm take their meals at the college.

There are a few apartments, furnished rooms, and small houses for rent on

the island. Students who wish to find their own housing are assisted by the

college whenever possible, but must bear in mind that the supply of rentals is

definitely limited.

Cars

Students are not encouraged to bring cars. However, those who choose to

reside at an appreciable distance from the college may find it necessary to

provide their own transportation. Students who bring cars are asked to pay a

$25 fee to contribute toward snow removal and parking lot maintenance.

Health

Prior to enrollment, students are asked to submit a physical examination

form, provided by the college, and prepared by each student's family

physician.

All students not covered by a parent's policy are required to participate in

a group Blue Cross policy for accidents and hospitalization. Normal medical

needs are the responsibility of the individual student.

Medical care is available at Mount Desert Island Hospital in Bar Harbor,

a three minute drive from the campus. Twenty-four hour emergency service is

provided by a local medical group as well as by several individual doctors on

the island.

9.

Informal Curriculum

From October to June, Mount Desert Island offers peace and tranquility to

a degree not found in the cities. To those used to the bustle of more urban

areas, Mount Desert Island in winter may at first seem either blessedly quiet or

desolately lonely. The island's particular combination of cultural, economic

and environmental patterns produces large amounts of open space and a com-

paratively reduced human presence. As they begin interacting in this milieu,

students may well find themselves developing life styles different from those to

which they have been accustomed.

The informal curriculum concentrates on those activities particularly

suited to a small co-educational college, located on the Maine coast, and de-

voted to the study of human ecology. The college does not provide programs

in intercollegiate athletics, and expects students to initiate whatever intra-

mural sports they may be interested in.

The college encourages and supports outdoor sports and recreation asso-

ciated with Maine. Mount Desert is surrounded by some of the most beautiful

sailing waters on the eastern seaboard. The island is rugged and mountainous,

criss-crossed by many miles of carriage roads and trails, suitable for hiking,

bicycling, cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, climbing, or just exploration and

solitude. The climate is tempered by an oceanic thermal effect; while winters

are cold, and summers warm, neither season experiences the extremes of

inland areas.

Special Supplies

Since many activities at College of the Atlantic stress outdoor involve-

ment, students should bring all equipment which they would like to use. Gear

for hiking, camping, fishing, photography and other activities is more easily

obtained in cities than in Bar Harbor, although some purchases can be made

here. Bicycles can be rented or bought in Bar Harbor. Air for SCUBA diving

is available on the island, but equipment is not. Bring binoculars if you can.

Foul weather gear will be welcome during some field trips. Hip boots or tall

one-piece rubber boots and old tennis shoes will be helpful during some col-

lecting trips.

10.

ARTS, CRAFTS, AND ACTIVITIES

With few exceptions, the college's cultural and social activities are student-

initiated and student-run.

The ceramics program, originally an extra-curricular activity, has been

incorporated into the curriculum as a year-long course directed by a profes-

sional potter with training in geology and petrology.

Like the ceramics program, the college's darkroom is open to the public,

and offers the opportunity for independent work as well as for practical instruc-

tion. Although no photography courses are planned for 1973-74, qualified stu-

dents are free to initiate independent study projects within the guidelines estab-

lished for student-structured work.

Other regularly-scheduled activities include folk dancing, spinning and

weaving, modern dance, and singing. Catherine Johnson, '73, organized a

group of madrigal singers for performances at the college, at local churches,

and elsewhere. Another student began a successful coilege literary magazine,

Voices of the Atlantic.

The college runs two separate film series. On Tuesday nights there are

showings of "eco-films," recently-made documentaries on different aspects of

animal behavior, pollution, and environmental problems and problem solving.

Every other Sunday evening, the college presents a feature film (Stolen Kisses;

Treasure of the Sierra Madre; Grand Illusion; etc.); films for this series are

selected by a group of students and faculty members with shared interest in

12.

the medium:

A number of dances, dinners, and concerts (one featuring Maine folk-

singer Gordon Bok), all organized by students, were held at irregular intervals

during 1972-73. The success of these activities suggests that they will con-

tinue, and will probably increase in number in years to come.

The college's gallery is under the direction of JoAnne Carpenter, college

Arts Coordinator. In its first year of operation, the gallery exhibited works by

local painters, photographers, and ceramicists; it was the scene of a special

regional photography exhibit, and of a third-term exhibit called Northern

Women: Art and Artifacts.

Distinguished visitors to the college during its first year of operation in-

cluded David Brower, President of Friends of the Earth; Maine Times editor

John N. Cole; and college trustee Rene Dubos. Speakers at the college's

summer forum included New Yorker film critic, Penelope Gilliatt; environ-

mentalist Donald Aitken; and Paul Shepard, professor of Human Ecology at

Claremont.

X

E

GOVERNANCE

Most policy decisions at College of the Atlantic are made and implemented

by five committees, consisting of students, members of the faculty and staff,

and trustees. In the event of a controversial decision, the committees are

authorized to call an all-college hearing for further discussion; should a de-

cision still not be reached, the committee chairmen and the president can con-

vene as the ultimate decision-making body.

The Academic Policy Committee is responsible for the continuing develop-

ment of the curriculum, including course offerings, changes in structure of

academic programs, and criteria and procedures for establishment and main-

tenance of academic standards.

The Personnel Committee is responsible for the recruitment, interviewing,

and selection of new faculty members. In making decisions, the committee

takes into account the opinions of all members of the college community. A

subcommittee is concerned with policy regarding contracts, salaries, and

fringe benefits.

The Committee on Admission and Financial Aid has two primary functions:

the establishment of admission criteria and the actual admission/financial aid

decisions; and, the formulation of policy concerning "student affairs" (housing;

employment; cars; medical care; etc.). Another important responsibility is stu-

dent recruitment.

The Evaluation Committee is charged with seeing that the "redefinition

and modification" mentioned in the Introduction to this catalog are facts and

not just words. Using multiple-copy forms and personal interviews, the com-

mittee determines and makes public the level of success in all college opera-

tions: president's office, classroom, and kitchen.

The Building Committee is concerned both with plans for the college's new

campus (liaison with architect; environmental impact statement; alternative

energy sources) and with the management and maintenance of the present

facilities.

In addition to the committee system there are bi-monthly all-college "town

meetings", called and chaired by students, for discussion of a broad range of

issues. By vote of a two-thirds majority, any committee decision can be sched-

uled for a community hearing.

The Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees has the ultimate

responsibility for financial decisions, and is the body to which the college

committees are accountable. Most members of the Executive Committee

serve on at least one of the college committees.

ADMISSION AND FINANCIAL AID

Admission Policy

College of the Atlantic welcomes applications from students who have

been prepared for college by their previous education and experience. Appli-

cants are judged on the basis of ability, preparation, attitudes, and enthusiasm,

and must be able to demonstrate an understanding of the college's goals and

methods. They should also have the potential to develop a social and aca-

demic life style compatible with a small college on the coast of Maine. Matur-

ity, self direction, responsibility, imagination, and resilience are among the

personal qualities judged most important.

The college seeks students who are qualified to benefit from its unique

curriculum. High school grades and test scores are neither the only nor the

best indicators of such qualifications. Accordingly, there is no set cut-off for

grades and SAT scores are not required. Nor are there any specific courses

required. A thorough and varied academic background is assumed, and a

strong secondary school preparation will improve a student's chances for ad-

mission. The admission committee also depends upon considerable and rea-

soned self selection on the part of students who are thinking about applying.

First-year students are usually admitted at the beginning of the fall term.

There is no deadline for the completion of applications, and no set date for

notification of the admission committee's decisions. Ordinarily, the commit-

16.

tee reads an application and notifies the candidate within four weeks of com-

pletion. Financial aid applicants, whose cases will often take longer, should

apply as early as possible. Within one month of notification of acceptance,

prospective students are asked to pay a $100 tuition deposit to insure holding

a place on the acceptance list.

Procedures

All candidates for admission are asked to follow several steps:

1. A PRELIMINARY APPLICATION should be submitted as early as pos-

sible. This will consist of minimum personal information and a 500-

1,000 word essay written in response to one of several questions re-

lated to current environmental issues. The essay will give the college

some sense of the student's style of writing, thinking and method of

problem approach. At the same time, students will engage in

processes the college deems important and will have sufficient time

to consider their purpose and motivation.

2. A VISIT TO THE CAMPUS is considered an important part of the ad-

mission procedure. Each application packet includes directions for

reaching the college as well as a description of overnight accommoda-

tions in the area. Arrangements for interviews must be made in ad-

vance. Applicants are encouraged to visit when the college is in ses-

sion, in order to form a clearer understanding of the college's goals

and demands.

3. THE FINAL APPLICATION consists of requested personal informa-

tion, a personal statement, two teacher recommendations and a school

recommendation form. Complete transcripts from all schools and col-

leges attended are also necessary. The application fee is $15.00.*

After acceptance, students will be asked to submit scores from all tests

administered by the College Entrance Examination Board.

*

The application fee may be waived for students with substantial financial

need, either by request from a secondary school or appropriate outside

agency, or by direct request from a student confirmed by the Parents' Confi-

dential Statement. No student interested in College of the Atlantic should

fail to apply because of the application fee.

Transfer Students

Qualified transfer students whose educational interests will be served by

transferring to College of the Atlantic are encouraged to apply for admission.

Transfer applicants are defined as those who have attended a degree-granting

college on a full-time basis for a year or more prior to enrollment at College

of the Atlantic. Official transcripts of all previous college work must be sub-

mitted. Application and admission procedures for transfer applicants are the

same as those for first-year applicants. Recommendations from both college

17.

and secondary school teachers are expected.

Transfer students must spend a minimum of 5 terms in residence at Col-

lege of the Atlantic. The exact number of terms needed for each individual

will ordinarily not be determined until after enrollment, when transfer students

will have had an opportunity to meet with their advisors and to discuss previous

college work with their teachers.

FINANCIAL AID

In distributing financial aid funds, College of the Atlantic assumes that

every effort will be made by the student and the student's family to contribute

to the fullest extent possible from their income and assets. When family re-

sources cannot meet a year's expenses, the college endeavors to provide addi-

tional support, in accordance with the need analysis procedures of the College

Scholarship Service.

Financial aid applicants submit a Parents' Confidential Statement, obtained

from secondary school guidance offices or from the Educational Testing Ser-

vice, Princeton, N.J. 08540. No financial decisions are made until the PCS has

been received, and applicants are urged to see that this form reaches the col-

lege promptly.

tudents may supplement scholarship awards with part-time employment

on ampus. Most inancial aid grants include a certain percentage derived

from the student's college earnings.

In 1973, the college will begin participation in a Guaranteed Student Loan

program, and, in 1974, in the college work-study program administered by the

U.S. Office of Education.

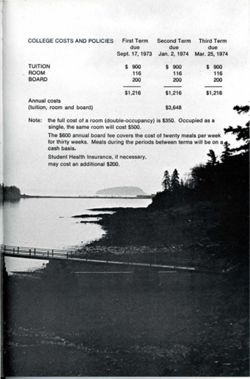

COLLEGE COSTS AND POLICIES

First Term

Second Term

Third Term

due

due

due

Sept. 17, 1973

Jan. 2, 1974

Mar. 25, 1974

TUITION

$ 900

$ 900

$ 900

ROOM

116

116

116

BOARD

200

200

200

$1,216

$1,216

$1,216

Annual costs

(tuition, room and board)

$3,648

Note: the full cost of a room (double-occupancy) is $350. Occupied as a

single, the same room will cost $500.

The $600 annual board fee covers the cost of twenty meals per week

for thirty weeks. Meals during the periods between terms will be on a

cash basis.

Student Health Insurance, if necessary,

may cost an additional $200.

EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM

The college's curriculum is based on a conviction that bodies of knowledge

are interdependent. Extreme specialization is incompatible with an under-

graduate education aimed at developing an understanding of human ecology.

The technologist who attempts to operate detached from his culture is like a

writer with a huge vocabulary but no sense of nuance. Both are likely to be

misunderstood and to create confusion. The broadly based, interdisciplinary

curriculum may also be described as the study of interrelationships and a con-

stant movement toward synthesis. The tendency to separate the study of man

from the study of the natural world is artificial, reflecting the limitations of the

human mind rather than the realities of nature. Similarly, the traditional struc-

turing of faculty into separate departments is a product of bureaucratic needs

which often ignores the fundamental interdependence of all fields of knowl-

edge. Synthesis, integration, communication, and application are the hallmarks

of the curriculum.

The curriculum consists of interdisciplinary workshops, courses and semi-

nars, independent study, tutorials, specialized skill courses, and supervised

internships away from the college. The emphasis is on analyses of human

ecology from different perspectives, and on understanding the complexities of

specific environmental problems. Skill acquisition and methods of problem

solving are other important aspects of the curriculum.

Our courses study the world as a system or organized structure, and the

courses themselves make up a coherent and interdependent system. We do

not neglect the practice of what we teach, and much of our attention is given

to ways of effecting practical change in the world once we have discovered

what these changes should be and what effects they will have. Therefore our

curriculum is divided into two parts, reflecting the practical and theoretical

concerns:

1) courses and seminars which emphasize patient and disciplined study

as well as creative experimentation, field work, and writing in all fields

related to Human Ecology. By learning both scientific methods and

humanistic values students will have a unique perspective that will place

them beyond the split of the Two Cultures and give them a humane and

expert approach to the rapid technological change that marks our period

in history.

2) workshops, in which students bring their knowledge to the practical

world and try to bring themselves and others into a more harmonious and

ecological relationship with their social and natural surroundings.

Advising

Three sources of advice are regularly available to each student. Faculty

members provide guidance on performance in each workshop, course or

seminar. Each student, moreover, chooses a faculty advisor to assist in plan-

21.

ning academic programs and reviewing progress. The student-advisor rela-

tionship is a very important one, and advising is considered one of the major

responsibilities of the faculty. In addition, the Director of Student Affairs is

available for counselling on academic or personal matters, and is prepared to

refer students for further help if necessary.

DEGREE REQUIREMENTS

Successful completion of the following six requirements will make a

student eligible for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Human Ecology.

1. Nine terms of academic work, six of which must be at COA. (One

term = one successful contract; internship does not replace academic work).

Note: this requirement stresses the importance of being at COA, in the com-

munity and with the people.

2. Essay in Human Ecology, to be completed before the first day of the

fifth term in residence. The essay, dealing with a specific practical or philo-

sophical problem, will be evaluated by two faculty members and one student,

and is regarded as a benchmark in the student's progression toward the final

project and the degree.

3. Workshop for one term, stressing environmental problem-solving, and

providing a medium for interaction and synergism between perspectives and

disciplines.

4. Laboratory or field work for one term. This should not be read as a

"science requirement"; rather, its purpose is to promote and stimulate research,

on either the group or the individual level.

5. Internship for one term (minimum) to one year (recommended). See

page 24 for a description of the college's intern program.

6. Final project completion and presentation, to come after the successful

completion of the preceding five requirements. Subject to approval by the

student's advisor and the APC, this work might require as much as a full year

for completion, and will be evaluated both by a special group of appropriate

faculty members and students and by qualified professionals and specialists in

the field of the student's endeavor.

The Contract System

Students at College of the Atlantic are expected to compose their own

programs of involvement. Aided by an advisor, students will strive to piece to-

gether an integrated "contract" which arises out of real educational needs.

The collection of contracts by a student who is ready to graduate will contain

examples of responsibilities assumed inside the college and larger communi-

ties; intense interaction with the natural world; experiences in group-solving;

original independent work which reflects a competence in a self-defined area of

human ecology. Students will have a deep sense of their own strength, and a

background preparing them for important work in the world.

22.

The college is concerned not only with intellectual growth, but with the

students' continued involvement in the social and natural world. Built into the

contract system is the flexibility for a student to develop learning programs

which include a great variety of individual and group experiences. The col-

lege views its role as supportive, and relies heavily on individual or group

initiative for the creation of personalized programs.

Contract Guidelines

Most contracts are for 10 weeks (one term). Contracts which include

projects covering more than one term are renewable at the beginning of each

term.

Independent study by incoming students is permissable, though not en-

couraged, provided that proposals are received before a student arrives at

College of the Atlantic, and that they follow established guidelines.

The student makes each contract in consultation with his or her advisor.

Contracts normally include at least three activities approved by the Academic

Policy Committee, i.e. courses, independent study, or workshops. The college

welcomes inclusion in the contract of social activities and involvement with

the natural world, recognizing that without them a student's life at College of

the Atlantic is likely to be one-sided and too narrowly focussed. However, the

APC concerns itself only with those activities which it has approved. It is the

responsibility of the student to find approved personnel to sponsor activities

which are not generally available through the college. If a student successfully

completes three APC-approved activities in a contract, that contract will be

considered satisfactorily fulfilled. (Students who wish to may undertake more

than three APC-approved activities in a given term. The number of success-

fully completed contracts is what matters.) Approved activities successfully

completed will be listed on the student's transcript. Unfulfilled parts of con-

tracts must be made up within one calendar year. Any student who must make

up parts of more than one contract at any time will be called before the APC

for mutual clarification. All information concerning a student's contracts

(content, completion, incompletion, etc.) will be included in the student's port-

folio, which will remain a part of the college records. Transcripts, to be sent

to graduate schools or prospective employers, will include records of suc-

cesses only.

Before the end of the first week of school in each year, all students write

a short (less than 3 pages) personal essay describing their general study plans,

goals and expectations for the coming year. Advisors receive copies and dis-

cuss them with the students. All essays subsequent to the first should include

evaluations of previous essays, in the light of experience. The final essay, at

the beginning of the last year at the college, should consider post-college

plans and goals, as well as reflections on earlier documents, and should in-

clude a plan of the final project. Once the essay is approved, it will be con-

sidered a commitment to that final project.

The final project proposal should be submitted to the student's advisor

and approved one term before the work is scheduled to begin. The APC must

23.

approve all final project topics. Normally this project will occupy the major

portion of a student's time. Successful completion will include a written report

(or equivalent) and a public presentation.

The decision to award the degree will be made by a four-member gradua-

tion committee, normally consisting of two members of the faculty/staff, one

student, and one person from outside the immediate COA community.

Guidelines for Independent Study and Student Structured Projects

1. Any independent study proposal must be accompanied by a written state-

ment from a COA faculty member with whom the student has taken a

course saying that the student is prepared for independent study. Incom-

ing students will need to make special arrangements.

2. Whenever appropriate, student-structured projects should be formed into

group projects.

3. All student-structured projects should be done in cooperation with a

college faculty member or an APC-approved sponsor.

4. Teachers should not be expected to be involved in an unreasonably large

number of projects in any given term.

5. In planning a project, student and advisor share the responsibility for

maintaining a balance between over-specialization and over-generalization.

6. Whenever possible, individuals are encouraged to try to fit their proposal

into the existing course structure.

7. Proposals for student-structured projects must be approved prior to the

beginning of the term in which the project is to take place.

8. All proposals must be submitted to the APC.

Intern Program

We seek opportunities to test the relevance of knowledge gained in formal

courses to employment opportunities which may be available following grad-

uation; to spend enough time working with others on a daily basis to sense the

frustrations and difficulties which are a part of every endeavor; to gain a per-

spective on the kinds of further training which will be the most helpful in making

us more effective in the work we choose, and to have the opportunity to pursue

those on returning to COA; and to make recommendations on methods to im-

prove the usefulness of the time spent in college classrooms.

Upon deciding to undertake an internship, students should consult with

their advisor or with a faculty member with some knowledge of the job area.

A proposal should then be drafted which states:

1. The type of job, and the responsibilities to be assumed.

2. The name and address of the person to whom the student will be

responsible during the job.

3. The nature of the financial arrangements made (including a proposal

for funding from COA when it is necessary and possible).

24.

4. The anticipated duration of the internship.

5. The manner in which the experience is to be evaluated.

6. Some statement regarding how the employer views her/his role.

The preceding proposal can be considered the contract for whatever

period of time the internship endures.

Internship proposals must be submitted during the term (or summer, in the

case of internships beginning in the fall term) preceding that in which the

internship is to begin.

Prior to beginning the internship, a student must have successfully com-

pleted the essay in human ecology.

Normally, two terms should be spent at the college after the internship

and prior to graduation in order that information and insights may be shared

with others, and so that the student may have the opportunity to gain further

skills which experience proved necessary for better performance on the job.

Students who wish to have work experience which was gained prior to

attending COA credited toward the internship requirement may do so only by

making prior arrangements with the college for evaluation purposes.

In order to make the program as self-supporting as possible, students

will make some payment to the college during the internship. This cost will be

determined and periodically reevaluated by the Executive Committee (present

recommendation, $200/term). The intern program will attempt to make assist-

ance available for such costs where the need justifies it.

On completion of the internship, a written report will be submitted to the

Evaluation Committee rating previous College of the Atlantic experience as

relevant to the internship, the experience itself as a teaching situation, and

other factors which the Evaluation Committee feels are of general relevance to

the college and to the success of the program.

CURRICULUM, 1973-74

Term II

Governmental regulation of human

effects on natural systems

Basic Humanities Sequence

Legal Research Laboratory

How to rite good (poetry)

Math/Physics

Woman: Her Arts and Artifacts

Ceramics

Art, the crafts and society

Human effects on natural systems

Environmental biology lab

Man in nature

Energy

Biology

Language and culture

Crime and society

Maine coast history to 1860

26.

Term I

Open to all

Landmark cases in environmental law

Basic Humanities Sequence

How to rite good (exposition)

Ecology of natural systems

Maine coast culture and open space

Cultural ecology

Woman: Her Arts and Artifacts

Math/Physics

Ceramics

History and philosophy of science

2nd yr. students or permission

Native Americans-philosophy. culture and

law

Biology

Thoreau seminar

Planet earth

Term III

Recent decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court

Basic Humanities Sequence

How to rite good (fiction)

Woman: Her Arts and Artifacts

The Human Family

Math/Physics

The family and social structure

Ceramics

Plants and people

Ecology as metaphysics

Maine coastal architecture

Consumer protection and unfair trade

practices

Biology

Economic anthropology

The Human Animal

II

In 1973-74, six courses will run consecutively for all three terms. While

most of these courses are divisible, students bear the responsibility for deter-

mining whether (and when) they may enter a three-term course.

Basic Humanities Sequence

W. Carpenter

This course will introduce the interpretation of artistic forms and the rela-

tion of humanism to Human Ecology as a discipline. It will integrate certain

principles of aesthetics, history, philosophy, and psychology to give the indi-

vidual student an understanding of his place in several simultaneous complex

systems besides the natural system: social, psychological, historical. Artistic

forms will be studied as modes of complex simultaneous perception of these

systems, that is, as modes of locating the individual perceiving mind in its

complete environment. The course will include discussions exploring the

aesthetic implications of ecology, the subjective meanings of modern scientfic

knowledge, the relation of artistic and natural forms, the historical and phycho-

logical roots of our attitudes towards nature and the "natural," and the current

attempts to derive a new theology from the teachings of the Natural Sciences.

29.

UNIT I: Art and Illusion. The interior and exterior landscape. Art as a mode

of perception. The relation of artistic and natural forms.

Sources: R. Arnheim, Visual Thinking

Paintings by Matisse, Van Gogh, Picasso, Hopper, Monet.

Wallace Stevens: "The Idea of Order at Key West"

"Anecdote of the Jar"

"Thirteen Ways of Looking at a

Blackbird"

Suzanne Langer, Problems of Art

UNIT II: Art and Experience. The relation of imaginative literature to psy-

chological and biographical experience.

Sources: James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

Dylan Thomas, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog

"Fern Hill"

"Poem in October"

"Under Sir John's Hill"

Class Production. Dylan Thomas, Under Milk Wood

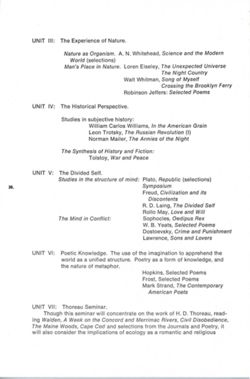

UNIT III: The Experience of Nature.

Nature as Organism. A. N. Whitehead, Science and the Modern

World (selections)

Man's Place in Nature. Loren Eiseley, The Unexpected Universe

The Night Country

Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

Crossing the Brooklyn Ferry

Robinson Jeffers: Selected Poems

UNIT IV: The Historical Perspective.

Studies in subjective history:

William Carlos Williams, In the American Grain

Leon Trotsky, The Russian Revolution (I)

Norman Mailer, The Armies of the Night

The Synthesis of History and Fiction:

Tolstoy, War and Peace

UNIT V: The Divided Self.

Studies in the structure of mind: Plato, Republic (selections)

30.

Symposium

Freud, Civilization and its

Discontents

R. D. Laing, The Divided Self

Rollo May, Love and Will

The Mind in Conflict:

Sophocles, Oedipus Rex

W.B. Yeats, Selected Poems

Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

Lawrence, Sons and Lovers

UNIT VI: Poetic Knowledge. The use of the imagination to apprehend the

world as a unified structure. Poetry as a form of knowledge, and

the nature of metaphor.

Hopkins, Selected Poems

Frost, Selected Poems

Mark Strand, The Contemporary

American Poets

UNIT VII: Thoreau Seminar.

Though this seminar will concentrate on the work of H. D. Thoreau, read-

ing Walden, A Week on the Concord and Merrimac Rivers, Civil Disobedience,

The Maine Woods, Cape Cod and selections from the Journals and Poetry, it

will also consider the implications of ecology as a romantic and religious

movement. Exploration of new religious possibilities based on earlier concepts

of Natural History and more recent discoveries in the Natural Sciences.

American transcendalism as a movement, Emerson Jones Very, the "Hudson

River" School of painting. Some descendents of Thoreau will also be exam-

ined, such as Henry Beston, J. W. Krutch, and Wendell Berry.

How to Rite Good

S. and M. K. Eliot

Term I (exposition) will focus on the distinction between writing correctly

and writing well. A knowledge of grammar, punctuation, spelling, etc. is

assumed. Students will develop their abilities to write with clarity and pre-

cision, to write persuasively, and to understand and employ the many different

types of figurative language. Where the rudiments (grammar, etc.) are weak or

absent, remedial help will be provided on an individual basis. Of particular

interest is the art of persuasion, as practiced through different logical and

rhetorical devices.

Term II (poetry). About two thirds of the time will be spent on considera-

tion of student work; the remainder will be spent with basic questions of form

and definition and with selections from the works of several poets who are

alive and writing, one or more of whom will be asked to visit the college.

31.

Term III (fiction) will be similar in structure to Term II, although the per-

centage of time spent on student (and teacher's) work might be as high as 95.

Discussion and criticism of each student's work will be supplemented by indi-

vidual conferences and by a few selected readings. Problems of style, tone,

and consistency will be considered. Sherry will be imbibed (in moderation, of

course).

Biology

S. Katona and F. Olday

In this course we will investigate the basic biological processes that

underlie the organization and diversity of life. During class discussions and

afternoon practical exercises, the concepts and information gained in text read-

ings will be related to environmental and personal concerns. Written reports

are required in conjunction with laboratory or field work. Each student will be

responsible for two pieces of original experimental work during the course of

the year. Work in groups is encouraged. Research results will be presented to

the class. Participation in this course is normally limited to students who have

completed the Natural Systems course sequence or equivalent preparation.

Texts to be used in this course are: CRM Books, Biology Today (1972); Wilson,

E. O., et al., Life on Earth (1973).

Physics, Mathematics and our Environment

C. Ketchum

A careful and quantitative analysis of our environment requires a knowl-

edge and understanding of the many physical processes involved in forming

and maintaining this environment. This course will introduce the basic physical

laws that determine these processes and develop the methods of mathematics

that help us clarify our understanding and extend our reasoning about these

processes. The emphasis in the course will be placed on the basic laws of

physics, the mathematical formulation of these laws, techniques for obtaining

solutions to relevant specific problems and the applications of these laws and

techniques to physical processes in our environment.

The presentation and discussion sections will emphasize an intuitive ap-

proach to physical and mathematical reasoning followed by extensive analysis,

proof and criticism. Historical notes and readings will indicate the develop-

ment of some of the most critical concepts. These sections will be supple-

mented with several problem sets, laboratory and field exercises.

The full three term course will introduce aspects of mechanics, calculus,

conservation principles of energy and momentum, simple harmonic motion,

elementary differential equations, wave motion, multidimensional calculus,

thermodynamics and applications to atmospheric and oceanic physics.

32.

Woman: Her Arts and Artifacts

S. Lerner

The arts are an important part of the culture which helps determine the

human environment. Courses in art often find themselves concerned mainly

with the creations of men. In this seminar, however, we will emphasize the role

of Women in the Arts. We will survey (Western) art (in its broadest sense:

literature, poetry, painting, sculpture, music, dance, photography, film, design,

crafts) as both an aspect of culture and a reflection of the individual's role in

society.

Term 1: 18th and 19th century artists

Term 2: 19th and 20th century artists

Term 3: 20th century artists and projects

Projects in the third term will develop out of new perspectives acquired

in earlier terms. One may work individually or in a group, creating or analys-

ing art.

The seminar will meet once a week for two hour sessions. It is open to

not more than 12 men and women.

Ceramics

E. McMullen

This course will offer the student the opportunity to cultivate visual and

tactile intelligence through the medium of ceramics. A working relationship

with both the technological and intuitive elements of ceramics will be empha-

sized in the following aspects of the course:

1. The study of the chemistry and geology of clay with emphasis on the

formulation of clay bodies for ceramics.

2. The development of technical skills and aesthetic sensitivities for

form, function, and design through a varied exploration of hand-

building techniques.

3. The study of glaze chemistry and formulation.

4. The study of glazing techniques.

5. The development of throwing and turning skills on the potters wheel.

6. The drying kiln setting and firing of ceramic objects.

The studio will be operated on an open workshop basis so that class time,

when necessary, can be given to structured group activities such as: an exam-

ination of past and present traditions in ceramics with slide viewing and re-

ports from available source materials; field trips to dig clay and glaze materials;

special workshops in Raku pottery using available materials and fuel; experi-

ments with the generation of methane gas as fuel for the kiln.

33.

FIRST TERM

Maine Culture and Open Space

E. Beal, Jr.

This course will give an introduction to the processes involved in culture

change and will focus on the relationship of land-use to the culture and the

individual. The Maine coast will be studied as one example of a land-use

pattern which is undergoing pressures to adapt and change. We will examine

this process from both the objective and subjective viewpoints, trying especial-

ly to understand what our own personal relationship to it is, how it affects us,

and we it. Readings (partial listing): Sarah Orne Jewett, Country of the Pointed

Firs: Charles Eliot, John Gilley; Clyde Kluckhohn, Mirror for Man; William F.

Whyte, The Last Landscape; The Allagash Group, A Maine Manifest.

History and Philosophy of Science

R. Davis

It has often been noted that in the twentieth century Western science and

technology have come to be the repository of an uncritical faith and confidence

which was once bestowed upon religion and ritual. This faith has been a major

factor encouraging a sanguine public attitude toward the warnings of environ-

mentalists. In turn, many environmentalists have been led into anti-intellect-

ualism by their own faulty conceptions of science, technology, and their inter-

relationships. Yet even if human disruption of the ecosystem were to halt

35.

immediately, we would still be dependent upon both to resolve the problems

that already exist.

Unfortunately, the popular mythology of scientific method and the scien-

tific revolution has distorted their character and obscured the inherent

strengths, weaknesses, divisions of controversy, and practical dynamics of

science itself. The purpose of this course is to dispel this mythology and

arrive at a conception of science providing a more informed basis for our

expectations of its foresight and applications. To achieve this end we must

carefully examine some of its major innovations and innovators within their

socio-historical contexts.

Material examined will include contemporary, modern, and ancient periods

in both Western and non-Western traditions. While reading assignments will

often be drawn from the works of scientific figures, they will be sufficiently

non-technical for general understanding.

Native Americans: Philosophy, Culture and Laws

R. Davis

D. Kane

L. Swartz

Who were these people called "Indians" by Europeans encountering the

New World? What kind of people were living in Maine during the period of

European exploration and settlement? What was their "world view", how did

they survive, and why were they oppressed by the white man? This course

will examine the cultural, philosophical and legal conflicts between Native

Americans and Western Europeans, how the Indians responded to the treat-

ment they received, and the life of today's Indian in Maine. Attention will be

given to the special plight of Eastern Indians and the current legal contro-

versies between the Maine Indians, the State of Maine and the federal govern-

ment. More generally we will consider the goals and methods of the con-

temporary American social movement and what might be our relationship and

what we might do at this time. This introductory course in Native American

studies involves participation by an anthropologist, lawyer and philosopher

and will be accompanied with field work in developing understanding of

Maine's Indians and their problems. One possible focus of attention is the

migrant farm laborers in Maine's blueberry industry; another, the legal battles

to reestablish relations with the federal government and to validate land con-

fiscation claims. Readings will include: Jennings and Norbeck, Prehistoric

Man in the New World; Jorgensen, The Sun Dance Religion; Black Elk Speaks;

Deloria, Custer Died for your Sins; Case Materials on Native American Rights,

Indian Law, and Conflicts of Law.

Landmark Cases in Environmental Law:

D. Kane

An Introduction to the Legal Process

36.

Through a detailed consideration of case histories in some exemplary

environmental controversies, the nature of the judicial process and of govern-

mental administration of natural resources will be explored. These studies

will also provide an introduction to the principles and fundamental concepts

of environmental law such as the public trust doctrine, standing, and the rights

of non-humans and ecosystems. The cases will encompass the human struggle

over precious natural areas such as Mineral King in the Sierra Nevada, the

Florida Everglades, and Storm King on the Hudson, and the persistent problems

of highway construction through parks, jetport expansion, alteration of rivers

and navigable waters by dams, dikes, bridges, and fill, and intrusion into

wilderness areas. Case materials will provide background in the historical and

ecological setting and pertinent environmental legislation, and follow the con-

troversy through each of its administrative and judicial opinions and decisions.

Planet Earth

C. Ketchum

In this course we will examine the general structure of our planet and

some of the physical processes that shape it. Simply put, we will try to under-

stand what makes our earth "tick". Our explorations will survey man's cur-

rent concepts of the structure of the earth's interior, the earth's surface, sea

floor spreading, continental drift, the physical properties of the atmosphere

and the ocean, atmospheric and oceanic circulation and the processes that

help produce our weather.

The lecture-discussion sections will be augmented with a series of selected

films, field observations and extensive readings from several paperback texts.

In addition a log of local sea state and weather observations will be main-

tained and discussed within the context of the course.

Ecology of Natural Systems

S. Katona

This course combines an introduction to ecology with an orientation to the

Mount Desert Island region. During the two weekly 1½ hour class sessions,

students will consider the processes and relationships which are fundamental

to the organization and integration of ecosystems. The first half of the course

is an autecological approach to the reciprocal relations between the organism

and its physical environment. Later, the relations within and between individ-

uals, populations and species are considered. The course provides a compre-

hensive introduction to the principles underlying the distribution, abundance

and diversity of life on earth. Readings will be from: Collier, B. D. et al.,

Dynamic Ecology (1973); Krebs, C. J. Ecology; The Experimental Analysis of

Distribution and Abundance (1972); Odum, E. P., Fundamentals of Ecology

(1971).

Coordinated with class discussions and readings will be a program of

films and a series of afternoon field trips to observe and study local examples

of various habitats, including inshore marine, intertidal zone, fjord, saltwater

37.

marsh, freshwater pond, bog, mature forest and burned over forest. Students

will gain experience with some fundamental techniques for doing ecological

investigations in the field.

Cultural Ecology

L. Swartz

What is called 'environmental improvement' merely consists in most cases

of palliative measures designed to retard or minimize the depletion of

natural resources, the rape of nature, the loss of human values, and social

unrest. Such programs can be regarded at best as short-sighted adaptive

responses to acute crises. They are expressions of fear or panic rather

than of constructive thought. (Rene Dubos, So Human An Animal).

If there is an ecological crisis, it is of our own making. It is in every one

of us. What are we to do about it? Can we go beyond our conditioning to ask

the unspoken questions which must be asked? Can we examine the way we

relate to our environment, the natural environment and the human environment?

Can we change, in a very fundamental way, the manner in which we live?

We will meet twice a week to discuss these questions and will read the

writings of Garrett Hardin, Rene Dubos, Lynn White, Margaret Mead, J.

Krishnamurti and others.

SECOND TERM

Communication in Culture Through Language

E. Beal and L. Swartz

Language is one of the most important means that human beings have to

communicate with each other. In understanding the relationship of humans to

the biosphere, we must recognize the key role of language in human life. The

degree of interdependence of language and thought, and of language and

culture, will be examined. Other relevant concepts are: the distinction between

structure and function; the ability of language to communicate values

(denotative and connotative aspects of language) and to communicate the

need to change values; the relation of other ways of life, including other ways

of speech, to our own; group identification through language (examples from

Maine). The basic text will be Dell Hymes (ed), Language and Culture in

Society: A Reader in Linguistics and Anthropology.

Arts, the Crafts, Environmental Planning and Society

J. Carpenter

This course will treat the place of art, the crafts, and environmental plan-

ning in society from both an aesthetic and an ethical perspective. The efforts

of the radical artist to resolve the contradiction between "high art" and the

39.

visual squalor encountered in the daily lives of most Americans will be con-

sidered as will the various efforts of the crafts to merge art and life. Innova-

tions in environmental design as well as improvements in the aesthetic of

machine made objects will be investigated. Readings will include: The Future

of Architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright; Sketchbooks of Paolo Soleri, ed. by Paolo

Soleri; Visionary Cities; the arcology of Paolo Soleri, Donald Wall; The City in

the Image of Man, Paolo Soleri; Survival Through Design, R. Neutra; Design

with Nature, lan McHarg; Art and Society, Herbert Read; The Lesser Arts,

William Morris; "Museum & Radicals", Art in America, Linda Nochlin; "The

Individual as Institution", The Planetary Horizons of Man, William Irwin

Thompson.

Man in Nature

R. Davis

This course will be an introduction to the general theory of value. The

capacity to resolve social and technological problems is useless without the

inclination to employ it. Problems are themselves only recognized as such in

terms of the values which they threaten and which define them as problematic.

Yet as entertained within our fragmented culture, values conflict and seem to

require conflicting solutions. Not only have environmental activists frequently

found themselves in conflict with economic and other interests, they have often

enough disagreed with each other.

Debates over the merits and relations of value claims rarely penetrate to

considering a basis for values in terms of which such issues might be resolved.

Perhaps this is because it is generally assumed that values are an artifice of

man while nature offers us only facts. To the contrary, if we acknowledge that

human systems are elements within nature, the concept of "bare fact" itself

may appear to be an artifice of those who have intellectually attempted to re-

move themselves from it.

The primary emphasis in the course will be placed on developing the stu-

dents' ability, as individuals and as a group: to exhume the bases of their own

value judgments; to critically examine their adequacy, consistency and co-

herence; and to constructively work toward synthesis in a viable value

"system". Reading assignments will be secondary to frequent papers express-

ing the individual student's own sense of importances and submitted to the

group for close discussion.

Governmental Regulation of Human Effects on Natural Systems

D. Kane

Coordinated with the study of Human Effects on Natural Systems, this

course will concurrently examine the principles of governmental and adminis-

trative regulation of power generation and energy consumption, water quality,

air quality, noise, solid waste, endangered species and habitats, pesticides,

and land use. Sample legislation by state and local governments in these

areas of concern will be analyzed drawing heavily on Maine, particularly with

40.

respect to the regulation of land use: site location of development, great ponds

and wetlands control, subdivision control, zoning, and land use regulation in

the "wildlands". Materials will also include court decisions elucidating prob-

lems and controversies in governmental regulation. The alternatives of direct

regulation of activity and indirect regulation through economic pricing of the

"real social cost" and "effluent charges" will be examined. Finally, the rela-

tionship of state and local efforts in each area to federal legislation will be re-

viewed in the context of the "federal system".

Legal Research Laboratory: Introduction to Advocacy

D. Kane

This introduction to the basics of legal research will culminate in the

preparation of a legal brief and oral argument by each student before a panel

of judges in a "moot court". During the winter term the group will meet once

a week spending a half day at the Hancock County Law Library learning how

to use the law reporter systems, annotated codes, treatises, encyclopedias,

digests, and other legal tools while researching and preparing selected cases

in areas of environmental law, consumer protection, civil rights, crimes, and

public interest law generally. Advanced students who have participated in the

moot court may choose alternatively to conduct legal research on a project

topic of interest with approval of the instructor, preferably related to subject

matter being covered in other courses in order to realize an interdisciplinary

perspective.

Deviant Behavior, Crime & Society

D. Kane

L. Swartz

How do individuals and societies deal with conflict? There are possibilities

of conflict resolution which are basic: overt physical confrontation (fighting),

and administered rules and conditioning. We are interested in studying ways

in which conflict is evaluated and handled, with particular emphasis on the

workshops of institutionalized legal systems. Some of the questions we shall

ask are: How do societies get people to conform to principles of "right"?

Why do some people engage in "anti-social behavior"? What are deviance

and crime? What is the difference between law and custom? What are some

of the different ways that different societies deal with "anti-social behavior"?

The class will examine how the United States deals with "deviance", "anti-

social behavior" and "crime" and the theories and principles of criminal

responsibility. Readings include: Malinowski, Crime and Customs in Savage in

Society; Clark, Crime in America; Bohannon, Law and Warfare; Goldstein and

Goldstein, Crime, Law and Society; Hart, Punishment and Responsibility; Hall,

General Principles of Criminal Law; The Bureau of National Affairs, The Law

Officer's Pocket Manual, The Criminal Law Revolution and its Aftermath, and

The Criminal Law Reporter.

Human Effects on Natural Systems

S. Katona

This course concentrates on the mechanisms by which the activities of

41.

humans have altered or threaten to alter the natural environment. Topics

included are energy crisis; environmental problems of power generation; alter-

native energy sources; pollution of water, air and soil; global environmental

problems; solid waste disposal; endangered species and habitats; introduced

species; pesticides and alternative methods of pest control; and the ecology of

modern warfare. Other topics are added or substituted when timely. Readings

are from a variety of primary and secondary sources.

The Environmental Biology Laboratory, taught by Dr. Olday, is designed to

coordinate with this course and will introduce students to a series of scientific

research tools useful in investigations on environmental problems. Govern-

mental Regulations of Human Effects on Natural Systems, taught by Mr. Kane,

is also structured to coordinate with this course.

Human Effects on Natural Systems, Laboratory

F. Olday

The laboratory associated with Human Effects on Natural Systems is de-

signed to extend the concepts and principles presented in the lectures to the

real world. Emphasis will be placed upon learning basic field and laboratory

techniques used in monitoring problems of environmental pollution. Proced-

ures of sampling, note-taking, analysis, compilation and interpretation of data,

and report-writing will be stressed.

One afternoon per week.

Energy Cycles in Natural Systems and Our Need for Power

C. Ketchum

Energy represents an ability to do work while power is the rate at which

energy is used in doing a given amount of work. Some sources of energy

available on this planet are the sun's radiation, fossil and nuclear fuels, tides,

atmospheric and oceanic motions and physical processes within the solid

earth. However, it is mainly the fossil and nuclear fuel sources that have been

developed by our technology. This factor coupled with limited resources in

fossil fuels, the problems of thermal pollution associated with nuclear energy

sources and a rate of energy consumption that in this country is doubling

almost every ten years, places the energy crisis at or near the top of the list

of critical environmental problems.

This course will explore our needs for and use of energy within the con-

text of the natural energy cycles operating on earth. The concepts of energy,

work and power will be clarified and the physical laws that govern the trans-

formation and use of energy discussed. These arguments will then be applied

to natural energy cycles within our environment as exemplified by solar, atmos-

pheric, oceanic, fossil and nuclear fuels and geothermal energy processes.

Our current power demands will then be discussed within this perspective.

Conventional power generation will be examined and the limitations and impli-

cations of fossil and nuclear fuels explored. The course will conclude with a

survey of alternative sources of power generation.

42.

THIRD TERM

Economic Anthropology

E. Beal, Jr.

Economic life is (among other things) the way in which humans use their

environment. Economic systems depend on sets of beliefs and values from

which have been formulated economic "laws", some of which are relevant

only to the culture in which they operate. Economic concepts will be studied

in various cultural contexts. Books will include John Kenneth Galbraith,

Economics Peace and Laughter, and Melville J. Herskovits, Economic Anthro-

44.

pology, among others. We will seek to differentiate between economic "laws"

and statements about economic behavior which stem from beliefs and values.

Maine Coastal Architecture

J. Carpenter

This course will direct itself to aiding Maine's Architectural Preservation

Society in completing the registration of Maine architecture with the Federal

Government as a means of preserving aesthetically and historically valuable

buildings in the state as well as "folk" forms such as the Cape Cod. Field

work (including photography and research) will center on Mt. Desert Island,

where many houses of architectural significance are still unrecorded. As a

prerequisite, however, the architecture of New England from the Seventeenth

through the Nineteenth Centuries will be surveyed stylistically, historically,

and philosophically, using towns such as Salem, Massachusetts; Portsmouth,

New Hampshire; Kennebunk, Wiscasset, Thomaston and Machias, Maine as

examples. Finally, the efforts of redevelopment groups in places such as Bos-

ton and Portland to use older buildings and neighborhoods as a nucleus for

urban planning will be considered in relationship to Maine coastal communi-

ties. Readings will include: Who Designs America, ed. by Lawrence Hollander;

Men and Movements in American Philosophy, by J. L. Blau; Experiencing

Architecture, P. Rasmussen; Timaeus, Plato; Greek Revival Architecture,

Talbot Hamlin; The Stick Style and the Shingle Style, Vincent Scully; American

Architecture and Urbanism, Vincent Scully; A History of Mt. Desert, Stories.

Ecology as Metaphysics

R. Davis

Metaphysics is the attempt to understand the most general features of

reality as presupposed in the study of limited systems. Epistemology is the

complementary effort to determine the basic character of the knowing process.

Here we will treat them as inseparable.

The basic premise of this course is the claim that in making models of the

world, man makes over the world itself - often in oblivion to the shortcomings

of his models and his methodologies of making them. To be a member of

society is to be possessed of one or more views of reality. However, though

these views may affect our interpretation of almost everything we experience,

we are rarely consciously aware of their complete character, their effects, their

implications, and their omissions. The result is that our most basic systems of

understanding may be destructively in harmony with other systems in nature,

until nature suddenly corrects us.

If we define Human Ecology as the study of man as an organism in rela-

tion to his environment, then Ecology as Metaphysics is the search for cognitive

equilibration of the many Systems given in nature - including cognitive

systems themselves.

Reading will reflect perspectives typical of both industrialized and non-

industrialized cultures as well as philosophically articulated proposals.

Consumer Protection

D. Kane

4

Sociological, economic, ethical, technological and legal analysis of the

major concerns of the consumer movement provide the focus for this course:

consumer fraud, creditors' practices, and deceptive trade practices and adver-

tising; dangerous products and products liability; the motorcar; food, drugs,

devices and cosmetics and their adulteration, contamination and misbranding;

consumption of professional services; and economic regulation. The theme of

consumption and the environment will be developed and the interface of en-

vironmental law, consumer law, and poverty law will provide an introduction to

the field of "public interest law". In addition to case materials readings will

include excerpts from: Schrag, Counsei for the Deceived; Reben and West,

Buyer's Guide to the Law; Keeton and Shapo, Products and the Consumer:

Deceptive Practises (Vol. I) and Defective and Dangerous Products (Vol. II);

Nader et. al., What to Do With Your Bad Car: An Action Manual for Lemon

Owners; Dacey, How to Avoid Probate.

Recent Decisions of the United States Supreme Court

D. Kane

Recent decisions of the nation's highest court will provide a focus for dis-

cussing vital social issues: abortion, contraception and the right of privacy;

newsmen's privilege and freedom of the press; obscenity and the First Amend-

ment; the death penalty and cruel and unusual punishments; discrimination,

equal protection and civil rights; and due process of law. The reading of indi-

vidual opinions will provide a familiarity with the diverse perspectives of the

nine justices and an understanding of the place in our society of this "court of

last resort". The notion of a fundamental right "implicit in the concept of

ordered liberty" and the natural law background in the Ninth Amendment will

be examined and an attempt made to develop a theory of constitutional rights.

In addition to case materials, readings include: Cardozo, The Nature of the Ju-

dicial Process; Rawls, A Theory of Justice; Black, "The Bill of Rights";

Holmes "The Path of the Law".

Plants and People

F. Olday

The purpose of this course is to have students gain a deeper appreciation

of the role plants play in their lives, from providing the basic necessities of

life to enhancing the charm of their surroundings. This is not a professional

course and hence avoids the technical; nor is it a comprehensive course as

there is no attempt to cover all that is known about plants. Rather, a few

selected topics will be dealt with to a depth appropriate for students having

little or no background in the sciences. It is a course in botany of interest and

appeal to human beings as human beings.