From collection COA College Publications

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Search

results in pages

Metadata

COA Magazine, v. 13 n. 2, Fall 2017

COA

THE COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Volume 13. Number 2. . Fall 2017

THE QUESTIONS WE ASK

COA

The College of the Atlantic Magazine

Letter from the President

3

News from Campus

4

New Faculty

6

Philip S.J. Moriarty

Board Chair

9

THE QUESTIONS WE ASK

10

Faculty

The Endurance of Questions

John Visvader

12

Question Queen

Karen Waldron

13

Stories

John Anderson

14

The Space Between

Nancy Andrews

15

The Forgotten. The Ignored.

Dru Colbert

16

Why Go On? Colin Capers

17

Does it Sound Good?

John Cooper

18

Students

My Summer with Großmutter

Maria Hagen 17

19

Something Good Will Come of This

Ursa Beckford '17

24

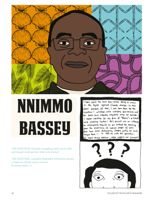

Nnimmo Bassey

Aneesa Khan '17

26

Artwork

Melancholia

Sean Foley

30

Politics

The Champlain Institute

34

The Bow Shop, an excerpt

Jack Budd '19

36

Poetry

Ite Sullivan '18

42

Alumni Notes

43

Books & Music

48

Community Notes

52

In Memoriam

55

The Education of Congresswoman Chellie Pingree '79

57

This spread: The historic center of Nuremburg, as seen from the Imperial Castle

of Nuremburg (see page 19). Photo by Maria Hagen 17.

Front cover: Sean Foley, Curses and Oaths, detail, 2017, oil on canvas, 33"x28"

The image is part of art faculty member Sean Foley's series Melancholia, an

interrogation of depression (see page 30). Writes Sean, "This is basically the

Irish flag behind the clover. Depression runs on the Foley, Irish, side of the

family. The four leaf clover was from a plant given to me by a dear friend to

cheer me up on my birthday. / planted it and it died. But / saved the clover.

Years later it became a subject in this painting."

COA

From the Editor

The College of the Atlantic Magazine

Volume 13 Number 2 Fall 2017

Editorial

What makes us who we are? What drives us? How close can we get to another's

Editor

Donna Gold

consciousness? To their perspective?

Editorial Advice

Heather Albert-Knopp '99

Rich Borden

These questions drove me to incessant reading as a child, to anthropology

Lynn Boulger

as a college student, and to journalism after college. They also pushed me to

Dianne Clendaniel

Dru Colbert

ask unanswered questions of my immigrant grandparents and my parents.

Darron Collins '92

There have been other questions: Can there actually be justice for all? Can

Lothar Holzke '16

Jennifer Hughes

humans of differing cultures, ideas, and ideals learn to live with each other?

Amanda Mogridge

Can we coexist with the natural world without destroying it? For years, these

Suzanne Morse

Matt Shaw '11

questions, and the search behind them, have been enriched by the passion

Hannah Stevens '09

of COA students-along with the staff and faculty I have worked beside. Such

Editorial Consultant

Bill Carpenter

commitment, charm, and humor blossoms here! Just read the essays, the

Design

questions, the devotion present in this issue.

Art Director

Rebecca Hope Woods

But the questions that we have as children, as young people; the questions

COA Administration

that live within us, cannot ever be placated. They propel our lives; they form

President

Darron Collins '92

us. For there is a quest, at least one, within each one of us. I am sure of it. And

Academic Dean

Kenneth Hill

while such questions are seldom followed by answers, they must be heeded or

Administrative Dean

Andrew Griffiths

Associate Academic Deans

Chris Petersen

we wilt inside.

Karen Waldron

For nearly fourteen years, I have sought to know, to understand, and to

Dean of Admission

Heather Albert-Knopp '99

Dean of Institutional

Lynn Boulger

reveal the beauty and mission of this college. I have been taught so much by so

Advancement

many here, and rewarded beyond any expectation. Now my journey must take

Dean of Student Life

Sarah Luke

a more personal form. As a journalist, as an editor, and as a writer, one of my

COA Board of Trustees

greatest privileges has been to hear the stories of people's lives, then present

Timothy Bass

Casey Mallinckrodt

these stories-not in my words, but in theirs-helping them to see their own

Ronald E. Beard

Anthony Mazlish

Michael Boland '94

Jay McNally '84

lives. This is work I've done for communities, for individuals, and also for COA.

Leslie C. Brewer

Philip S.J. Moriarty

From people who spent their lives cutting wood and driving buses, to creating

Alyne Cistone

Lili Pew

Barclay Corbus

Hamilton Robinson,

computer code and building libraries, these stories have fed me; I long for

Lindsay Davies

Nadia Rosenthal

more.

Beth Gardiner

Abby Rowe ('98)

Amy Yeager Geier

Marthann Samek

And so, since I cannot be two people, I am retiring from this magazine to

H. Winston Holt IV

Henry L.P. Schmelzer

my own work, to enable myself to listen more, and to continue my Personal

Jason W. Ingle

Laura Z. Stone

Diana Kombe '06

Stephen Sullens

History efforts, helping families and communities record their stories.

Nicholas Lapham

William N. Thorndike, Jr.

Coincidentally, Rebecca Hope Woods, the college's graphic designer, is

Life Trustees

also leaving. For nine years she has shepherded the visuals of the magazine.

Samuel M. Hamill, Jr.

John Reeves

Beyond her amazingly swift design capacities and precise proofing skills, she

John N. Kelly

Henry D. Sharpe, Jr.

has inched me on to become a more visual reader. Rebecca is someone who

William V.P. Newlin

asks the most startling but basic questions, like why are you doing this? What

Trustee Emeriti

David Hackett Fischer

Philip B. Kunhardt III '77

are you trying to achieve?

William G. Foulke, Jr.

Phyllis Anina Moriarty

This letter is almost too difficult to write. I will miss COA and this magazine,

George B.E. Hambleton

Helen Porter

Elizabeth Hodder

Cathy L. Ramsdell '78

which was launched quite casually one morning when Steve Katona, president

Sherry F. Huber

John Wilmerding

at the time, said something to the effect of, I'd like you to start a magazine.

What a gift! What a challenge! Just as COA is not like any other college, this

The faculty, students, trustees, staff, and alumni of

magazine had to be imbued with human ecology, with interdisciplinarity, and

College of the Atlantic envision a world where people

value creativity, intellectual achievement, and

with the overall humanity evident in the questions, the quests, that you will

diversity of nature and human cultures. With respect

find from students, faculty, staff, and alumni throughout this issue. I have

and compassion, individuals construct meaningful

lives for themselves, gain appreciation of the

learned so much from this effort-from you, the readers, from this very special

relationships among all forms of life, and safeguard

community, from its struggles and its triumphs. COA will always be a cherished

the heritage of future generations.

part of my life, along with COA, the magazine. I can't wait to read and admire

COA is published biannually for the College of the

what the new editor and designer create.

Atlantic community. Please send ideas, letters, and

submissions (short stories, poetry, and revisits to

human ecology essays) to:

COA Magazine, College of the Atlantic, 105 Eden St,

Bar Harbor, ME 04609, or magazine@coa.edu.

WWW.COA.EDU

Dam Gold

PRINTED WITH

Donna Gold, editor

MIX

CERTIFIED

Paper from

responsible sources

WIND

FSC

www.fsc.org

FSC® C021556

POWER

From the President

Darron greets families and alumni on Thorndike Library's porch during COA's Alumni and Family Weekend welcome reception.

Photo by June Soo Shin '21.

If you've read the facing page, you know that this is

questions constantly, and the one I've been unable to

Donna Gold's last issue as COA editor. We will miss her

shake involves skepticism and belief. At COA we place

dearly! I will miss her dearly. For fourteen years, Donna

tremendous value on questioning and ask students to be

has bottled the essence of College of the Atlantic in the

wary when they feel steeped in certainty. The question I

pages of this magazine. Her editorial direction has spoken

would add to the others outlined on page 11 is, Do we live

to alumni, donors, friends, and prospective students in

our lives in a continuous state of doubt or is there room to

our distinctive accent, leaving a diverse readership with

truly believe?

an intimate understanding of a very special place.

I'd need a lot more space than I have here to explain

One way she's made this publication reflect the ethos

where I currently stand on that koan. Donna's a stickler

of the college is by building the stories and histories

on word count.

around a theme or a question. At COA we love questions.

On a more practical note, I've also asked what's next

Human ecology is all about picking up a question as you

for the magazine following Donna's departure. After

would a stone, turning it over in your hands to bathe it

briefly considering a half-year pause, we've decided that

in the light of different angles and varying perspectives.

there's just too much going on: faculty hires, a building

Where is this stone from? What is it made of? How did it

project, students arriving, alumni off shaping how the

get here? How might I use it? It makes sense that Donna's

world works. The magazine is a glue that holds our past

last magazine would be a question about questions.

together with our future and we don't want those things

I'm teaching this fall. Seven faculty members, COA

to come undone.

alumnus and trustee Jay McNally '86, and I are working

So, we are excited to welcome Dan Mahoney as guest

with first-year students in a class called the Human

editor for our Spring 2018 issue. Dan is a poet and a

Ecology Core Course. I didn't take on the responsibility

writing instructor at COA. He has also recently revived

lightly: could I balance what I I needed to do as president

the Bateau literary journal, bringing it to the college. It will

with the demands of teaching? Halfway through the term,

be thrilling to see where he takes us.

I am convinced it is a perfect use of my time.

I have a home crew of thirteen students, but will

get to know every single first-year because the home

crews rotate through the instructors. There's a student

from the West Bank, from Iran, from Peru, from The

County (Maine's Aroostook County), and from nine

other states in the United States. Their diversity in origin

matches their diversity in interests. We wrestle with

Darron Collins '92, PhD

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

3

NEWS FROM CAMPUS

APRIL

AUGUST

Kimberly López Castellanos '18

Christina Baker Kline, author of

receives a prestigious Udall

Orphan Train, discusses her latest

Scholarship for her work merging

novel, A Piece of the World, on the

climate justice activism and

relationship between the artist

communications strategies.

Andrew Wyeth and Christina, the

Photo by Ana María Zabala Gómez '20.

subject of his painting Christina's

BREAD & PUPPET THEATER

A student-led Diversity Initiative

World, with art faculty member Dru

COMES TO COA

opens community discussions to

Colbert.

strengthen diversity on campus.

COA hosts the memorial celebration

MAY

for David Rockefeller.

Violinist Augustin Martz '17

SEPTEMBER

performs concerts downtown at

St. Saviour's Episcopal Church and

The academic year opens with

the Jesup Library, and on campus

certified nurse-midwife Aoife

in Gates, the Blum Gallery, on the

O'Brien '05 speaking to most

North Lawn, and the pier.

of COA's 350 students from 45

countries and 41 states.

Senior project presentations

COA CLASS OF 2017

examine HIV/AIDS, midwifery in

With the help of local restaurant

Guatemala, the 17th century writer

Havana and Michael Boland '94,

Aphra Behn, seeds, electric vehicles,

the Share the Harvest Farm Dinner

tiny houses, whales at the South

at Beech Hill Farm brings $7,371

Pole, and more.

to Share the Harvest's mission of

extending fresh, organic, and local

Page Hill '17 creates a pollinator

produce to low-income Mount Desert

garden behind the Davis Center as

Islanders.

her senior project.

"COA is committed to making

JUNE

education open and accessible,"

including accepting undocumented

and DACA applicants and

SELLAM CIRCUS

Seventy-eight students from

"maintaining the privacy of all

SCHOOL CAMP

25 states and 15 nations

student records," writes Darron

receive diplomas and flowers at

Collins '92, in an open letter to the

commencement. Poet and essayist

community.

Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib offers humor

and optimism as speaker.

OCTOBER

Darron Collins '92, COA president,

signs the "we are still in" statement,

Gear up with the new online store

pledging to sustain and expand

from Allied Whale thanks to Siobhan

efforts to mitigate climate change.

Rickert '17. Tees, hats, bottles and

His letter is published in the

more support turtle, seal, and whale

Hechinger Report.

stranding responses. Find the Allied

Whale store at coa.edu.

BAR ISLAND SWIMMERS PLUNGE

INTO THE NEW YEAR

JULY

Family and Alumni Weekend hosts

a screening of Burning Paradise,

Talks abound throughout the

the award-winning movie on the

summer, ranging from Lucas St. Clair,

president of the private nonprofit

indigenous ecology of southern

Mexico by Greg Rainoff '82.

that donated the 87,563 acres of the

Katahdin Woods and Waters National

Acadia National Park rangers and

Monument, to Muslim scholar and

COA students collaborate for the

poet Reza Jalali, to trustee emeritus

David Hackett Fisher on his

spooky Nature of Halloween, a

night of fun and finding at the Dorr

upcoming book on African

Museum of Natural History with

cultures in America.

insect treats, genuine bones, and

POP-UP ART AT

nocturnal creatures.

OTTER CREEK HALL

4

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

NEWS

Greenest College. Again.

Ratings Season: Sierra,

Princeton Review,

Washington Monthly, US

News & World Report

For the second year in a row, College

of the Atlantic was rated the greenest

college in North America by both

Sierra, the Sierra Club's magazine,

and Princeton Review's annual Best

381 Colleges. Sierra's ranking is based

on a lengthy, comprehensive annual

survey, reviewing the environmental

commitment of 227 colleges and

universities.

"In the new millennium, concerns

framework, which has students

who 'foster an environment open to

for the environment must be

partaking in the entire process

discussion.' Conversations extend

wedded to social justice and central

of work, both on campus and in

outside classrooms all of the time;

to everything we do," said Darron

the community, from policy to

COA 'is a college and a community

Collins '92, COA president, in

preparation to implementation.

that demands cognizance,

response to the Sierra notice. "Our

"At COA we measure our success

compassion, and trust."

students will lead the way in this

by how much students learn and by

effort, and the more they are directly

how successful they are at applying

involved with the hard work of

that learning out in the world," said

"Conversations extend

creating sustainable campuses and

Darron. "If we were 100 percent off-

outside classrooms all of

communities, the more they will gain

the-grid and carbon negative, but

the time."

the skills and confidence to create

students didn't learn a thing in the

-Princeton Review

the future we all deserve."

process, it would not do us much

In celebrating COA's status, Sierra

good."

mentioned COA's commitment "to

In addition to celebrating COA

When US News & World Report

diverting 90 percent of campus

as the greenest college, Princeton

came out with its rankings, COA was

waste by 2025, [and] its Hatchery,

Review ranked COA as #2 in the

again placed among the top one

an incubator for sustainability-

category "LGBTQ-friendly," #8 in

hundred colleges, in the top twenty

oriented student enterprises such

both "professors get high marks" and

"best value schools," and as the

as [Re]Produce (see page 8).

"most active student government,"

liberal arts college with the sixth

Other students are engaged in an

#10 in "most liberal students," #11

highest percentage of international

initiative to provide local farms

in best campus food, and #14 in

students.

and businesses with solar power

"students study the most."

Finally, COA was ranked in the

financing consultations. Classes meet

In a narrative quoting COA

top twenty of liberal arts schools

at adjacent Acadia National Park, on

students, the publication notes,

by Washington Monthly, which asks,

two organic farms, and twenty-five

"Students don't just take classes,'

essentially, What do colleges and

nautical miles south of campus at an

they immerse themselves in

their alumni do for their country?

island research station dedicated to

experiences and in 'an intimate,

the study of marine mammals."

friendly community' of doers and

Sierra's full ranking and each school's

COA's sustainability efforts are

critical thinkers.

Students can't

completed questionnaire can be

outlined in a student-created energy

say enough about their professors,

found at sierraclub.org/coolschools

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

5

NEWS

Susan Letcher botanist

In the spring of 2000, just about a week after she

where one question leads to the next." Still, she preferred

graduated from Carleton College, Susan Letcher, COA's

working with flora over fauna. "Cutting a branch is not like

new botanist, stood atop Mount Katahdin with her sister

severing the limb of an animal," she says.

Lucy, beginning a hike from Maine to Georgia on the

For Susan, coming to COA meant leaving a tenure-track

Appalachian Trail. A classical pianist and composer, Susan

position at the State University of New York's Purchase

had taken a double major in biology and music. The time

College. Beyond her longing for the island, the nature

to choose was upon her. She pondered these paths as she

of the college has lured her: "the way students track

walked the trail. Barefoot.

their own path through human ecology as leaders and

"We'd always hiked barefoot, running around

thinkers," as well as the expectation of plenty of time

mountains in Acadia National Park," says Susan, who

outdoors doing field-based teaching.

grew up on Mount Desert Island, graduating from MDI

And yet, Susan's research hasn't been in Maine, but

High School in 1995. "Barefoot, there's a deeper sense of

in the tropics, studying the regrowth of forests in Costa

connection-you experience the forest floor, the granite."

Rica after such disturbances as the slashing of great

It's a connection she's carried into her work as a botanist,

swaths of trees for cattle ranches. She has studied more

exploring the granular diversity of numerous forests.

than thirty sites, noting the plants that return, how they

But first there was the hike. When the sisters got to the

relate to each other, their evolutionary history. Beyond

end of the trail in Georgia, says Susan, "spring was just

seeking to understand the environmental forces involved

coming to the woods, the idea of leaving, of driving home

in assembling communities, Susan hopes to apply that

on a highway when flowers were blooming on the forest

knowledge to restoration.

floor, of going back to a mostly indoor life-I couldn't do

"Plants are so amazing," adds Susan. "Pretty much any

it." They returned to Maine, yes, but on foot. Soon after,

weird thing that you can think of, plants are doing. Their

Susan began working toward her doctorate in ecology and

whole body surface is a receptor for the environment."

evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut.

They also communicate, she says. "If an herbivore starts

Plants have always fascinated her. "They're so different

chewing on a plant, volatile compounds are triggered

from us, and yet they have to resolve the same basic

and sent to other plants, and they'll start changing their

issues of how to make a living on earth-but without

chemical composition, preparing for attack."

the power of movement or a central nervous system-

Susan hopes to take students to Costa Rica next year.

things we animals take for granted." Hikes and garden

But she also plans to bring them around MDI. Fascinated

work launched Susan's interest in plants; an internship

by diversity, she's been examining the immense array

at the MDI Biological Laboratory deepened her analytical

of lichens, mosses, and liverworts on the island. First

abilities. "I loved the scientific process, figuring out how

though, she has another task, caring for her infant, born

to ask the right questions, developing lines of inquiry

mid-October.

6

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

NEWS

Netta van Vliet anthropologist

When Netta van Vliet applied for COA's visiting position

University of Jerusalem. It was a year fraught with political

in anthropology nearly four years ago, she was primarily

drama, "events that likely influenced my direction," she

following a directive from her advisor to search for jobs.

says. Netta was at the peace rally where Prime Minister

She had remained at Duke University after receiving her

Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated. On another day, she held

PhD, and was teaching there, had friends, a home. She

off joining some classmates on a crowded bus-and heard

was quite content.

the blast as it exploded one block away. Later, she became

Then Netta came to COA-and fell in love. "It's a

involved in demonstrations against the Israeli occupation

stunningly beautiful campus," she says. Beyond that, she

of the West Bank. The next year she transferred to Lewis

noticed COA's sense of democracy in action, "how people

& Clark College in Portland, Oregon.

in structurally different positions interact," those working

While Netta has also conducted research in

and eating in Take-a-Break, for example. "There was

Guatemala, her focus remains on Israel and the Middle

something about the quirkiness of everyone I met, and

East. Her work centers on issues of difference-not only

the place," she continues. "I was intrigued that someone

of class and ethnicity, but also sexual difference and its

in the arts, and someone else in the sciences, and an

relation to other categories of difference, generated in

historian were all at the same table."

part by the questions posed by various political contexts.

But like so many who come to COA, it was her

How do people decide how to respond to violence? What

encounters with students that made the strongest

is non-violence in a context that is already violent? When

impression. "I didn't realize how much I could enjoy

do people think it is right to violate the law in order to

teaching until I started here. Before, I didn't envision

achieve justice? What are the genealogies of thought

myself teaching at a liberal arts college." But COA was

through which ideas of nonviolence, justice, and law take

different. "The kinds of questions students ask really push

shape? And, ultimately, what does it mean to be human?

me." When offered the visiting position, Netta accepted.

These questions often do not have easy answers, but

When it was renewed, she accepted it again-twice.

they demand a response, says Netta, whose own work

And when a full-time faculty appointment came up, she

is interdisciplinary, drawing on the fields of postcolonial

applied for that. "Teaching here reminds me why I'm doing

studies, literature, psychoanalysis, and feminist theory.

what I'm doing."

"Finding a good question can be at least as valuable as

Netta's background is multinational. Her mother is

finding answers," she says.

Israeli, her father Dutch. Born in Canada, she soon moved

The questions keep coming. The responses, in part,

to the United States. After spending time in Central

can be found in such classes as Possession and the

America and Israel following high school, she completed

Human, Transnational Feminist Theory, Waste, and The

her first year of undergraduate studies at the Hebrew

Human Non-Human Interface.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

7

NEWS

'S'N

Profiting from Waste

Summer in the Park

Solar in Ghana

Grace Burchard '17 and Anita van

Hands-on experience is fundamental

Thanks to a $10,000 Projects for

Dam '19 (left to right in photo) made

to a COA education. So is time spent

Peace grant and the efforts of Sara

news when they won a $5,000 cash

in Acadia National Park. A new Acadia

Löwgren '20, a primary school in

prize from the University of Maine

Scholars program does both, funding

east Ghana now has ten solar panels

Business Challenge for their start-up,

a summer internship in Acadia

and four new computers, offering

[Re]Produce, last May. The concept

National Park for two to three COA

affordable, reliable, and sustainable

of [Re]Produce is to turn farm

students.

energy, plus information technology

surplus into frozen food, increasing

Noah Rosenberg '18 worked

instruction.

farm profits, reducing food waste,

in communications in the park's

Sara, who hails from Sweden,

and enabling Mainers to buy local

Schoodic region over the summer.

connected with Sakyikrom United

produce year-round.

Gemma Venuti '18 focused on

Primary School or SUPS in Ghana's

Forty-five contestants vied for

invasive plants management,

Eastern Region when she co-led a

the prize, which also includes $5,000

measuring, plotting, and removing

group from her high school, United

of in-kind services, all donated by

invasive plants with the park's

World College Red Cross Nordic, to

Business Lending Solutions. The

exotic plants management crew. The

help fix its roof. While there, she

entrepreneurial pair are on a roll,

work, said Gemma, "was fantastic.

learned that school leaders longed

having tied for first place at the 2016

Fieldwork is what I want to do. Now,

for energy that would be sustainable

Maine Food Systems Innovation

when I apply to jobs, I can confidently

and reliable.

Challenge at Bowdoin College.

say, I'm able to do these things, and if

As one teacher explained, SUPS

"With this win, we got a lot closer

you hire me I can do them for you."

students are among the poorest in

to making this dream a reality,"

Noah created videos and wrote

Ghana. Few homes have electricity,

says Grace. Adds Anita, "People are

stories about Schoodic history,

let alone computers. But now, with

becoming more aware of food justice

scientists, and park personnel

energy and computers at the school,

issues, and food waste is on top of

for his internship, extending his

students can hope to gain computer

that list."

interdisciplinary education. He

literacy and thus also consider higher

Having worked with COA's

recalls a day spent "with a group of

education. Additionally, enrollment

Sustainable Business Hatchery to

educators, worm diggers, clammers,

will likely increase, allowing SUPS

develop prototypes and a business

and park scientists, talking about

to join the state food program that

plan, the pair is now refining the plan

intertidal uses. I really understood

provides a daily lunch for students.

as they seek appropriate processing

the importance of being open to

Projects for Peace was created in

facilities in Portland, Maine. In the

what you don't know and listening

2007 by philanthropist Kathryn W.

meantime, they're attending the

to people. I might not have been

Davis. To celebrate her hundredth

Clinton Global Initiative University

able to understand these different

birthday, she committed one million

and other gatherings to increase

perspectives had I just been a

dollars to fund one hundred student

their understanding of hunger, food

biologist."

projects in the hopes of increasing

security, and strategies that consider

A grant from the Endeavor

peace through grassroots actions.

the triple bottom line.

Foundation funds the program,

The projects continue. Says Sara,

"This is about taking our passions

which began with seed money from

"Investing in schools benefits an

into the real world," concludes Grace.

the Davis Conservation Foundation.

entire community."

8

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

DONOR PROFILE

COA's New Board Chair

Philip S.J. Moriarty: Keeping the Magic Flowing

by Donna Gold

"I'm a matchmaker," says Philip

S.J. Moriarty, who this summer

became the chair of College of the

Atlantic's board of trustees. Having

begun his career in admissions at

Yale University, his alma mater, Phil

moved to human resources at the

noted advertising company

J. Walter Thompson before launching

the Chicago executive search

consulting firm of Moriarty/Fox in

1974.

Connecting people, assessing

strengths, understanding risks-and

helping others do the same-has

been Phil's life. So when COA was

searching for a new president, nearly

seven years ago, Phil chaired the

committee that ultimately hired

Darron Collins '92. Phil is still proud

of his involvement in what he calls

this "terrific" choice.

Academic communities are

encouragement, along with that of former board chairs Sam Hamill and Bill

something of a home to Phil, whose

Foulke, Phil became a trustee in 2005.

father served as the Yale swimming

The match evokes Phil's own college career. When it came time for him to

and diving coach for forty-four

choose a major, he was interested in too many subjects to focus on a typical

years, "always learning, always

course of studies. Instead, Phil chose Yale's new offering, an interdisciplinary

probing," despite never attending

major in American Studies. "It captured me because it was multi-disciplinary,

college. In addition to serving as an

including economics and history and art and political science and literature."

ambassador through sport, the elder

"COA is an extension of my passion," says Phil. "I am intrigued by its

Phil Moriarty coached the US team

newness, the opportunity to continue to learn, and the educational model of

in the 1960 Rome Olympics. Later he

human ecology-self-directed, interdisciplinary, and practical." Enumerating

published ten volumes of poetry. As

the college's specialness, Phil emphasizes its mission and geography, and "the

the eldest son, Phil was the first in

remarkable people that work here-the great faculty, devoted staff, dedicated

his family to enroll in college.

leaders-and my generous and thoughtful colleagues" on the board of

Phil came to know COA in the

trustees, as well as the "participatory approach to governance."

early 1980s when Robert Ramsey,

And then there's the students, "their tremendous potential. I'm always in

his former supervisor in Yale's

awe when I hear them speak so eloquently, without any trepidation, on point,

admissions office, came to Maine

articulately-and to trustees. How intimidating can that be? I couldn't have

to consult with then-president Lou

done it at that stage in my life. You know they're going to find the right path

Rabineau on how best to move

and be successful as they carry COA's mission into the world." Phil pauses.

the young college forward. Phil

"There's something else too, I've often referred to COA as the little college that

remembers being intrigued by how

could

and does. It really does."

imaginative, creative, and pertinent

As chair, Phil follows Will Thorndike, who led the board from 2012 to 2017.

COA was. Years later, his friend

"He was terrific," says Phil. "Valued by his fellow trustees, a great partner for

and summer Northeast Harbor

Darron, and a wonderful salesperson for the college to the world beyond

neighbor, the late trustee Alice

campus."

Eno, reintroduced him. With her

As to Phil's goals, they're simple: "Keep the magic going."

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

9

THE

Questions

WE ASK

We know that COA is a mission-driven institution.

That mission is not just words on paper. It flourishes in the hearts and

minds of every member of the COA community.

We care. We inquire. We persist.

10

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

What creates a dream?

What does it mean to be

Do you love yourself?

Samuel Evans '21

human and alive?

Sara Anderson '21

Khorshid Nesarizadeh '21

What keeps me engaged

How do we choose our

as a positive influence?

How do you create a world

commitments when every arena

Toby Stephenson '98, staff

that simultaneously builds

in society is under attack?

environmental, social, and

Etta Kralovec, former faculty

What are the connections

economic abundance?

between nature and human

Jay Friedlander, faculty

How can I express myself

creativity?

authentically and strive to

Bill Carpenter, faculty

Can we sustain the ecological

understand others so we can best

needs of soil, plant, animal, and

connect?

How are we bodies together,

human within the bounds of

Jacqueline Ramos Bullard '07

surviving towards death?

available on-farm resources, or

Izik Dery '17

will external inputs be required?

How can we create a more

CJ Walke, staff

meaningful economy, one that

How does the college develop

is just and sustainable, and also

If the rainforests are the

a sustainable financial model,

recognizes that work is more

balancing the budget while

green lungs of our planet,

than earning money-it's a space

and the ocean is its blue heart,

maintaining the idealistic

to fully express our humanity.

how much of your heart do

Davis Taylor, faculty

qualities and goals upon

you want to protect?

which we were founded?

Melissa Chan '18

How dare the representative

Andy Griffiths, staff

of a leading nation affirm that

What does it mean to listen

climate change doesn't exist and

How do I use my life to help

and to learn?

also provoke the political climate

reduce the amount of suffering

Jodi Baker, faculty

to initiate nuclear war?

felt by others while still

Mariana Cadena Robles '17

maintaining my own health,

Does who we are now reflect

given my disabilities?

the premise upon which we

How might we create the

Elizabeth O'Leary '03

were founded?

language, institutions, and power

Marie Stivers, staff

structures for a culture in which

How can I help?

peace would not be obscured but

Amanda Mogridge, staff

What is the next right action?

be experienced as a constant and

Morgan Hildebrecht '17

vibrant presence?

What do you want to

Gray Cox, faculty

contribute to this world?

How can we rethink our world

Sahra Gibson '17

and ways of being by examining

What is the relationship between

in detail other places and times

microbes, our body's ecosystem,

How do we turn what is inside

that reveal how others have made

and that of microbes and humans

out and bring what is outside

their way in the world?

on the planet, and how do we

within as effortlessly as water

Todd Little-Siebold, faculty

learn to understand that?

flowing in a self-sustaining

CJ Kinton '84

circle of transformation?

What makes COA what it is?

Deborah Wunderman '89

Jill Barlow-Kelly, staff

What is human ecology?

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

11

The Endurance of Questions

John Visvader, faculty member in philosophy

Ever since childhood I've felt that there was a certain freedom in knowing things. Being alive was like being in a strange city

without knowing your way around. Everything seemed amazing and mysterious at the same time. Having a map gave one the

freedom to find one's way about, to make the place your own, to know where it was worth going and how to get there. I spent

a lot of time finding out how radios, clocks, and automobiles worked by taking them apart and putting them back together.

There seemed no end to the whys and hows of things. But finding a familiarity with practical things still left unanswered the

great orienting questions of childhood: Who am I? What am I? What is this place I'm in?

As I got older these kinds of questions became more specific but their answers remained elusive: What is the basis of

human nature? How does consciousness fit into a material world? What is the nature and origin of the universe?

The questions, put in this form, could be pursued academically, and so my schooling was split between psychology on the

one hand and physics and cosmology on the other. The pursuit of these questions by means of these disciplines seemed to

approach the answers only asymptotically-approaching closer and closer but never quite making contact. It seemed that the

kind of explanation that worked for clocks didn't do much for the bigger questions.

Midway through college, I discovered that both religion and philosophy were comfortable with unanswerable questions,

though religion concentrated on finding ultimate answers while philosophy thought the questions were more important.

Some philosophers felt that each generation, as a condition of their humanity, had to deal with the same or similar questions

but work out answers appropriate to their time and circumstances. There were enduring questions but not enduring answers.

In terms of the original analogy of the city, there were good and bad maps of each city but no master map that would get you

where you needed to go wherever you happened to be. Nonetheless, mapmaking remains a necessary and noble pursuit. This

view does not imply a radical relativism but rather expresses a deep pluralistic contextualism. I've found this approach to

these kinds of questions both humbling and in an important sense-freeing.

12

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Question Queen

Karen Waldron, faculty member in literature and theory

Several years ago, a student called me the Question Queen. I realized that most of what I do in class is pose questions:

questions of my own, questions in response to student questions, questions in response to student comments, questions in

response to my own comments. With words or without. Questions are the life force. We all have different questions and much

of my work involves helping students find their questions, often hidden within, because that's how I learned.

I'm sure I was one of those children who constantly asked Why? My questions were cosmic, not practical, though I was

always outside, learning the shapes of trees, the feel of dirt, the patterns of bird song. When I had my first flat tire my dad had

to teach me to question the earthly realm, not just abide there. In school during the sixties, I had come to focus on the nature

of the universe, existence, faith, pain, and suffering. My Why is the sky blue? questions had rapidly developed into ones about

racism, pollution, and war. In college I discovered the root of these in questions about time and consciousness. How should

I abide, embodied, in a broken world? Was there any earthly place for healing? My culminating project at Hampshire College

was all about the tension between poetry and philosophy in T.S. Eliot's work. I read it all, but especially Four Quartets.

From Burnt Norton:

From The Dry Salvages:

Time present and time past

But to apprehend

Are both perhaps present in time future,

The point of intersection of the timeless

And time future contained in time past.

With time, is an occupation for the saint-

No occupation either, but something given

From Little Gidding:

And taken, in a lifetime's death in love,

We shall not cease from exploration

Ardour and selflessness and self-surrender.

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Time. Place. Consciousness. Embodiment. The Four Quartets are each named for places. Maybe that is how we abide. Places

shape and teach us their own particulars while time and consciousness are vehicles of our questions. The poem expresses the

place; the place inspires the poem. The wells of wisdom in each seem infinite. Where and how do we apprehend the point of

intersection of the timeless with time? I read Jung; I read theology; I read philosophy. I went to graduate school not only to

read more novels and poetry and theory, but also to keep asking questions of them. Literature manifests a consciousness of

truth in time that probes the deepest levels of the mind and questions what it means to be alive-embodied in a particular

place, at a particular time. Discovering the mind of the novel and then rereading that novel at different times and in different

places becomes as rich an experience as knowing a person: endlessly fascinating, both finite and infinite. As Jorge Luis Borges

was so apt at narrating, the human consciousness can imagine infinity, can feel infinite, but we live and die in time. Every one

of our students is a human consciousness living in a finite body. Consciousness, like the universe, is endless. My questions

help me to live there while my body sends down roots to place and acknowledges time.

T.S. ELIOT

T.S. ELIOT

T.S. ELIOT

T.S. ELIOT

BURNT

EAST

THE DRY

LITTLE

NORTON

COKER

SALVAGES

GIDDING

FABER AND

FABER AND

FABER AND

FABER AND

FABER

FABER

FABER

FABER

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

13

The BBC's Civilisation: Part 5 of 13-The Hero as Artist with

Sir Kenneth Clark (1969). https://youtu.be/h5fjKgI1ljM

What Are the Stories We Tell Ourselves?

John Anderson, faculty member in ecology and natural history

I have always wanted to be a teacher. I remember one of my earliest COA advisees saying that the thing she liked best

about her second four years at COA was "watching John learn how to teach." I am not very good at it, but I am still trying.

I sometimes think that there can be no higher high than when a class really zings, when you realize that you have gone ten

minutes over and nobody seems to want to leave. Of course, there is also the lowest of lows-classes that crash and burn and

send me away cursing myself and obsessing over lost opportunities and my complete inability to make a point or keep to a

thread of argument. I suspect that the one can't help but having the other, and if I ever feel that I have really "learned how to

teach" it is time to quit.

I love research and cannot imagine not doing it, but research alone isn't enough. Part of that is that I lack discipline. If

I am honest, I agree with John Steinbeck and his best friend, the ecologist Ed Ricketts: I go because I am curious, and my

curiosity is perhaps overly wide for modern science. I am just as interested in why there was once a Bay of Gulls on maps of

Mount Desert Island as I am in the feeding range of the herring gull, but I also want to know why the United States went into

Vietnam, when the first humans reached Australia, and what Alexander the Great thought of the Romans.

This sort of variance suggests the mind of a dilettante, a charge that I should perhaps plead guilty to, but I justify it with

my obsession with stories. I think it no accident that one of the earliest things we say to each other is Tell me a story. Stories are

us, we are made of them, and as they change so do we. Here is a story of what drives me:

In the days when color television was very new, and we had only one friend who had a color TV, Sir Kenneth Clark hosted a

wonderful series on Western civilization. Every Thursday we went along to the Manns to watch Sir Kenneth walk us through

the glories of three thousand years of art and architecture. At the very end of the series he looked straight into the camera

and read Yeats' great prophetic poem, The Second Coming. Then he told us what he himself believed-a lovely short speech that

began, "I believe that order is better than chaos, creation better than destruction. I prefer gentleness to violence, forgiveness

to vendetta. On the whole I think that knowledge is preferable to ignorance, and I am sure that human sympathy is more

valuable than ideology." Then he turned and walked away, and the camera backed off and backed off, and I saw that he was

walking through a great library and was going to put the book back on its shelf. I realized then (I was probably only eight at

the time) that what I wanted to do was to read every book in that library. I want it still.

14

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

The Space Between

Nancy Andrews, faculty member in performance art and video production

One thing that drives me as an artist is a need to make things: films, drawings, objects, assemblages, music, animation-

forms vary-as a practice to keep me grounded in my realm of sanity. The process and engagement with making delivers me

into what Mircea Eliade calls ritual time-a time that releases me from the world of the everyday into the world of mystery

and transformation. Often my work with images, ideas, and materials is more intuitive and instinctual than intellectual or

purposeful. Once the work has developed, I can make more sense of what it means.

It is like dreaming-I create dreams while asleep and then examine them and gain understanding while awake. I am not

saying that I go into some sort of trance in the woods. I research, read, learn, investigate, collaborate, and all of that is fodder

in the process of making art.

The questions that engage me center around the grey areas between binaries, like death and life; human animals and non-

human animals; artificial and real. I am fascinated by the nature of reality and perception. I gravitate to big questions: What's

it all about? and What does it mean to be a human animal? and What gives my life meaning?

TAB.

XXVIII.

Nancy Andrews, sketch on Anatomy by John Fotherby, 1729-30.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

15

The Forgotten. The Ignored.

Dru Colbert, faculty member in arts and design

What does not get looked at or acknowledged?

What is willfully ignored?

How does the disregarded align with notions of the aesthetic?

A great deal of the world is overlooked, most of the time, in

microenvironments such as under bluestem prairie grass, or

varying degrees. If not, it would be difficult to concentrate

in the town of Otter Creek, Maine.

on anything amidst enormous sensory distraction. But what

In my current artistic practice, I have been collecting

is chosen as something to ignore?

evidence of humans in the form of discarded or lost things,

Stories speak of the nature of humans. What stories have

while also documenting plant life along the dead-end

not been collected? What stories are not being told? What is

road where I live. These gatherings range from flattened

ignored in individual lives, in psyches, in cultures?

beer cans and cigarette butts to botanical specimens and

I deal with these questions in my work as an educator,

collected sounds. Each object becomes a touchstone of the

in work I do with cultural institutions such as museums,

very particular story that brought it there.

and in the idiosyncratic work that I make as an artist. I

The discards of humans are as much a part of the

have sought to bring forth stories of people and events that

ecological makeup of a place as plants, animals, and

were previously hidden or submerged, whether they are part

geological material, telling tales of often overlooked lives

of our national story or tiny events that have unfolded in

and stories.

Dru Colbert, 2017, found object assemblage, digital print.

As a part of her current studio work, faculty member Dru Colbert is exploring relationships between aesthetically disparate realms by pressing the

seemingly worthless refuse of human-ness into botanical specimen arrangements.

16

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Why Go On?

Colin Capers '95, MPhil '09, lecturer in writing,

literature, and film

Why go on? I know to some this sounds like a desperate

question, at best a cynical and at worst a despairing query

to resort to. But it's a fundamental question-fundamental

for contemporary Western thought but more than that,

primal, rooted in the preverbal. It is Hamlet's question,

more concisely stated and without the simplistic duality.

The question need not be a dark one; fear of death and

taboos against the embrace of one's own mortality need

not taint our perspective. I see cinema and literature as

realms in which we may collectively investigate other ways

of framing human thought and experience-on this and all

questions that intrigue us.

The foundational inquiry of all disciplines can be read

as variations on why go on and its attendant questions:

How go on? Why begin? How begin? Why end? How end? These

questions inform any creative act (and I, for one, would

hope for a world in which all acts are creative). Of course

there are those, from Primo Levi to Kurt Vonnegut, who

offer compelling evidence across the spectrum of despair

to optimism that there is no why at all, or at least no use in

asking it-not to mention the Buddhists who would also

question the spectrum I just invoked. I tend to be wary of

the questions' implications of meaningfulness, but as long

as we are wary we may proceed.

These questions inevitably lead me to Samuel Beckett,

whose characters, from Murphy who "would never lose

sight of the fact that he was a creature without initiative"

to the unnamed voice of Fizzles 4 who "gave up before

birth." They are also at the heart of my interest in his work.

His radical, ongoing reduction is what first spurred me

to become suspicious of narrative. Stories can become

traps when we fail to recognize that they are contrivances,

procrustean beds to which we subject all that lies beyond

our ability (or desire) to comprehend.

Jonathan Heron and Nicholas Johnson, in a Journal

Valtman's

of Beckett Studies discussion of genetic literary criticism

(which reviews the history and variants of a given text,

attempting to reconstruct the author's process), ask "How

Caricature of Samuel Beckett holding a book, by Edmund S. Valtman

does an actor hope to produce a fulfilled performance

(1969). Courtesy of the US Library of Congress.

without full consciousness of an accurate source text?"

I think this is the dilemma which faces the human

ecologist: in a world with so many variables, how do we choose a course of action? But the belief that we have an "accurate

source text"-a clear, true, unchanging map for how to proceed-blinds us to the pesky, unsightly, human bits that may make

that text "inaccurate." And if we are uncertain as to how, the question why naturally follows.

Ultimately, questions of going on fascinate me for two reasons. Firstly, everyone has a different answer, and in encouraging

individual discovery of and engagement with these answers, we encourage a richer range of human knowledge and

experience. And secondly, the asking-why go on-every day in itself affirms the possibility of an answer.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

17

Photo by Rob Levin.

Do I have a quest? Yeah: Does it sound good?

John Cooper, faculty member in music

I sit at the piano, my baby grand, downstairs. All my great ideas come from sitting at the piano. I find a melody, a motif, a

chord. Some musical subject emerges. Mostly it's just emotion-I'll play a melody and it'll bring a smile, a memory, sometimes

a tear. It could also be a rhythm. Being a jazzer, I think of rhythm as a melody without the notes, rhythm adds gait, pattern,

pause. I'm not trying to tell a literal story, it takes a life of its own.

The hardest thing is not coming up with too many ideas.

When I get that basic idea, I try to remain true to it. I go upstairs where I have a keyboard and computer. Everything

builds. I can't take the jazz out of my compositions because I've listened to, analyzed, and played it all my life-or the Beatles,

or the Beach Boys, or Steely Dan, or Coltrane, or Shostakovich, or Prokofiev, or Sibelius.

In composition, there are vertical and horizontal aspects. Once I have an A theme, a B or C theme comes in as a contrast.

Legato to staccato, major to minor, smooth to angular. That's the horizontal. I draw in the listener. There's the melody-it's in

the flute now. Vertical is the chord, the harmony, the minor and major sounds.

What I have now is the melody and bass line, and enough harmony to determine what the composition is going to be. That

takes about a week. And with that there's the flexibility to go anywhere. With a large work it takes another month to bring it to

fruition. If you want to move forward, you've got to try new things.

Working on the synthesizer, and the many sounds it delivers, gives the timbre but not the balance. On a computer, the

flute can be as loud as a trumpet. So up to the day of that first rehearsal, there's that anxiety, wondering whether my clarinets

were going to cut through, and so on. Or maybe I'm struggling with a transition. And you have to know when to stop. I can

sit at the computer and add counter lines, harmonics. At some point I'm just doing it for effect. You can get so hung up with

creating music that is so harmonically rich-all those instruments to write for-that the melody gets lost. You've got to be

careful that what you add doesn't take away from the piece. Sometimes you have to say, Enough.

Every time is a little different, that's what's fun, exhilarating-and scary. You're opening yourself up: Is that what this

person is really about?

18

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Senior Projects

My Summer with Großmutter

THE QUESTION: How was an entire country convinced that deporting people based on their religion, sexual

orientation, political beliefs, or physical ability was acceptable or even necessary?

THE RESPONSE: My Summer with Großmutter: I Didn't Understand What Happened Then; That's Why I Remember

by Maria Hagen '17 with Annemarie Hagen

In 2016, Maria Hagen '17 spent the summer living in Nuremberg, Germany with her grandparents, her Großmutter and

Großvater, "as a way for me to answer questions about the time during and after World War II in Germany," the country where

Maria was born, but not raised. Maria's grandmother was born in 1935, a year after Adolf Hitler became Germany's president,

in addition to his role as chancellor. Maria wanted to know about a child's life under Hitler, but also how a nation in ruins

from war grew to be the most powerful country in Europe. How did people respond to the harsh conditions of destruction and

poverty? How did they rebuild? "Understanding this seems to me to be the only way to stop a similar movement in the future,"

Maria writes. The following excerpts are from her senior project essay.

A relative's home in Neuhaus, Germany where Maria's grandmother evacuated to

in 1942 with her mother and twin sister, escaping the Allied bombing of Munich.

All photos courtesy of Maria Hagen '17.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

19

PARADES

"Once, just once, did we go to a parade. Mutti, my

mother, wanted to see Mussolini, il Duce," recalls Maria's

Großmutter, Annemarie. She and her twin sister,

Ruth, were living in Munich at the time. Mutti, says

Großmutter, "probably wanted a reminder of her life

in Milan, a happy time, except for the death of her first

baby days after its birth. Mutti took us to a store owned

by a friend and we stood in the window. We could just

see Mussolini and Hitler go by, saluting. And then they

were gone and we went home. That was the extent of our

political education."

Großmutter pauses, pouring coffee, then continues,

"The Hagen side of the family was completely different.

Großvater was constantly surrounded by politics. His

aunt brought a stool to every parade so that she could see

over the crowds. And she was not the only one who did

that."

WAR

Having watched a movie with her grandparents that

glorified young Turkish patriots, Maria relates her

distress over "this pride in military power, so abundant

in the United States. I am angry at the need for power,

for killing, and disrespect for lives that aren't American."

Großmutter looks at Maria and replies, "Americans have

never had a war at home. They don't remember what it

is like to sit in a bomb shelter and watch the latch jump

higher and higher with each explosion while the old

lady next to you keeps saying der nächste Schlag wird den

Kindern die Lungen rausreißen, the next blast will tear the

lungs out of the children."

In 1942, with Allied bombs threatening Munich,

Annemarie and Ruth, just seven years old, fled to

Neuhaus, a village north of the city, with their mother,

leaving everything behind. Their father was not with

them. He was on the front, fighting for Hitler.

"I was shot at once by an American Tiefflieger, a

strafer, a low-flying aircraft with guns," Großmutter tells

Maria. "I was on my way home from school. I had my

Schulranzen, my school bag, on my back. I was walking

along the field. I was almost home. He flew so low I could

see the little cap on his head. And he fired at me. I threw

myself into the ditch. He shot at a child with a school bag."

EXPECTATIONS

Top: Annemarie Hagen, or Großmutter, in Nuremberg, Germany, 2016.

The twins were suddenly former city girls with nothing

Bottom: Annemarie Hagen in the 1960s.

to their names, dependent on their country relatives for

everything. And their family had ignored the expectations

of what a German girl should be under the Nazi regime;

rules disseminated in newspapers, in cartoons, on

placards, and advertisements:

20

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Deutsche Mädchen tragen Zöpfe. German girls wear

braids.

Notes Maria, "The twins had missed the

announcement and stood out with their short brown

A

5

253

507

407

bobs. When the war ended their hair was finally long

T36

T35

114

508

enough to braid, but by that time all the other girls wore

500

500

G

500

500

W-Brot

Brot

Brot

W-Brot

W-Brot

bobs."

LEA

Deutsche Mädchen weinen nicht. German girls don't cry.

Scot

134

Brot

Brot

135

Brot

Brot

"And they tried, but they had lost everything and they

BU@

BU

125g

BuG

Bue

22

R

Butter

missed their father. Everything was strange and they

250

250g Fett

never fit in."

S

11 C

S

BLUEPRINTS

11

Fleifch

Fleifch

Fleifch

Z11

Z11

Fleisch

Fleisch

Fleisch

Continues Maria, "The house was big, but by the end

503

27

26

25

403

405

7

11

5

of the war, when refugees from the east were put up

Fleifch

125

Z11

Z 11

Fleisch

125

FLEISCH

502

404

in the house as well, twelve people shared the one

Fleilch

125

Z11

Fleisch

125

toilet on the second floor. Eight people shared the one

501

22

101

16111

downstairs. There was no toilet paper, so Mutti tore up

old architecture magazines to use instead. Annemarie

Food stamps from the 1940s, allowing for 1,200 calories per day. This

amount could cause an average man to lose about two pounds a week.

would sit on the toilet trying to piece together the pages

so she could examine the blueprints. The paper was thick

and heavy, and the articles and prints so fascinating. But

as soon as she had two pieces together someone would

knock. Locking the door was strictly forbidden."

"At night, sometimes, you could see the moon over the

HIER WOHNTE

HIER WOHNTE

field when you stood on the toilet lid," says Großmutter

HENRIETTE

DR. IGNATZ

STEINHARDT

with wonder in her voice. "I would wake up Ruth and

STEINHARD

GEB. WERTHEIM

we would balance there, gazing at the moon. Everyone

JG. 1869

JG. 1882

thought we were crazy."

GEDEMUTIGT / ENTRECHTET

DEPORTIERT 1942

TOT 2.1.1933

IZB ICA

ERMORDET

ESSAYS

"Großmutter found out much later that Neuhaus, with its

Protestant population, voted entirely for the Nazi party

HIER WOHNTE

HIER WOHNTE

in the 1930s." writes Maria. "The next village over, which

PAULINE

DOROTHEA

was Catholic and Jewish, was less predictable than the

STEINHARDT

STEINHARDT

Protestant towns. They were more likely to understand

JG. 1905

JG. 1912

what was happening, and what the Nazi Party meant for

FLUCHT 1934

FLUCHT 1934

them.

ITALIEN

ITALIEN

"In school, der Nazi Gruß, the Nazi salute, was held

1936 PALASTINA

1936 BALÄSTINA

for hours," recalls Maria's Aunt Ruth. "You thought it

was over and then you just had to keep holding your arm

up." Adds Maria, "Schoolchildren were presented with

Stolpersteine, commemorative brass plates, literally "stumbling stones,"

information about their Jewish peers, all of it false. They

a work in progress created by the artist Gunter Demnig, to be placed in

wrote essays about it, repeating back to their teachers the

the sidewalk outside the last address of choice of the victims of National

Socialism. To date there are more than six hundred such markers in

lies and prejudices they were taught."

Germany, and many more throughout Europe. The artist cites the Talmud

Later, Maria finds similar essays in a Nuremburg

saying, "a person is only forgotten when his or her name is forgotten."

museum. "There is one essay, a single sentence in

unsteady cursive, proclaiming that Jews are dirty and

stink. It was written by a six-year-old. I almost throw

up. I understand why Großmutter does not attend these

exhibitions."

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

21

UNCLE JOHANNES

Großmutter's Uncle Johannes was a minister, but

because he had a Jewish mother, he could not get

a good position in a church. Writes Maria, "He

found a job working with the Jewish population

in a small town instead. The only way to help

them was to get them out, so Johannes arranged

for them to get fake passports, organizing ways

for them to sneak out of the country. It was

dangerous work, especially in a small town.

"Johannes finally received a ministry

position in a small village, but under

surveillance from the Nazis. The farmers in

the village all knew what he had done, and they

often brought him new people when they showed

up in town:

"'Pfarrer, Pfarrer, hier ist wieder einer.' Father,

Father, here's another one.

"One night, when Johannes and his wife had

already moved their child's bed away from the

window so she would be safe if someone decided

to throw rocks through the glass, Johannes

heard something outside. He went downstairs

to see what was going on. Outside he saw his

neighbors standing at the edge of the property.

"One of them came and told Johannes: 'We

are keeping watch, halten Wache, in case they try

to take you away.'"

In Munich, alongside others who stood in

resistance to the Nazi regime, there is a plaque

honoring Johannes' memory.

HUNGER

"People bought food with stamps," Maria writes.

"Each tiny square reserved a certain number

grams of meat, butter, bread, or flour for each

person. Men were awarded the most amount of

food per month while the rations for the elderly

were often so small it was not enough to live on.

Rations for a normal person amounted to 1,200

calories per day. If you lost the form with all the

stamps, then Pech, there was no other way to

obtain food. For people living on farms it was

often easier to get by than in the cities where

there was no way to grow a little food on the

side.

"On Saturdays, if the girls swept the town

square, they got a free bun from the bakery run

by their uncle. They were tough buns, called

Gummiklößle, rubber buns, but when food is

scarce, anything is good enough.

"Sometimes the girls begged for fresh fruit.

The family sent the children to the other houses

Annemarie Hagen and her twin sister, Ruth, in Nuremberg, Germany, 2016.

22

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

to ask for an apple or two. After all, people are more likely to

REMEMBER

give hungry children food. Annemarie would talk while Ruth

Großmutter says it's up to us.

stood just slightly behind her. Annemarie hated having to

My generation. The young people.

ask neighbors for fresh fruit.

It's up to us to remember.

Annemarie's mother made some money as a seamstress,

continues Maria. "Sometimes her customers paid in eggs,

Two years ago she took me to a protest.

or a liter of milk. Sometimes that milk had a bluish tint,

At seventy-nine, she stood for refugees in the cold.

giving it away as skim. Then Mutti was upset. Once she

She remembered,

sewed for three days for one customer who gave her ten eggs.

three grandchildren stood with her.

Annemarie thought it was an amazing amount of food and

could not fathom Mutti's anger.

Remembering is the debt we owe the dead.

"We never had anything fancy to eat, like carp, goose,

or duck. But sometimes we had a pigeon. Our grandmother

Germany over all, Hitler said, and rose.

would stuff it to try and make the bird look bigger, but even

America first, Trump said today, and rose.

then, with five people, a single pigeon isn't much meat." And

I went into the Holocaust Museum in Washington and

so they scavenged. "We gathered every edible plant, brewed

remembered.

every herb into tea. Grains were roasted to make coffee

His words were an insult to the people whose memories and

substitutes."

stories are kept here.

"I marvel at Großmutter," Maria adds. "Here we are,

His supporters' presence, jarring and hypocritical.

sitting in the sun with our feet up, sipping coffee and eating

fresh Streuselkuchen that she baked this morning, piled high

The next day I marched,

with whipped cream. The contrast leaves me breathless, but

one pink hat in the crowd,

she just pours herself more coffee and offers me noch ein

Großmutter's words heavy on my shoulders.

Stückchen Kuchen."

"Remember," she says.

Maria Hagen '17 and Großmutter in the summer of 2016.

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

23

Something Good Will Come of This

THE QUESTION: Who are the opiate addicts of Maine?

THE RESPONSE: Something Good Will Come of This, a documentary film by Ursa Beckford '17

"My whole town became addicted-people who drove the firetruck, the selectmen of my town. Last year alone, I attended

seven family gatherings for overdose deaths, from southern Maine to Downeast, people that I can actually look back on and

smile, knowing it was a good time."-Mike Bills, from Something Good Will Come of This

Having focused on conflict resolution and film at COA, Ursa

Then Ursa met Mike, an articulate and candid man now

Beckford '17 sought to create a documentary on Maine's

in his thirties who had spent years addicted to opiates. "The

opiate crisis for his senior project. Something Good Will Come

two of us got together for coffee," says Ursa. "He told me his

of This is a striking, compassionate portrait of Mike Bills, a

story. It was a profound tale of loss and redemption. From

recovering addict. Through him we obtain a glimpse into the

that moment on, I knew I wanted to make a film that would

journey from legal prescriptions to heroin addiction that has

capture Mike's story of addiction, providing hope about the

overtaken not only Maine, but the entire nation.

drug crisis that is devastating families and communities

Ursa had been planning to create a film about the

across the country."

Restorative Justice Project of Belfast, Maine, an organization

The film has no narration, no music. It portrays Mike

that seeks justice, rehabilitation, and reconciliation with

through his own words, along with those of his mother

the injured parties and the greater community. The project

and a few others. Mike tells how his addiction began while

also works with a reentry center to provide therapeutic

playing soccer as a student at Maine Maritime Academy.

programing, educational opportunities, community service,

After he suffered a concussion, he was prescribed three

and other approaches to recovery for addicts.

very strong narcotic painkillers. The high was like nothing

24

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Opposite: Mike Bills walks along the Searsport, Maine shore, not far from his home. Above: In the two years since Mike has been drug-free, he has become a

skilled finish carpenter and a father. Says Mike, "Ever since I've had Finn, I've started to change my whole entire life to fit him. There's nothing else, there's

no other priorities in my life, except him now." The film will be available on Vimeo and YouTube.

he had experienced before. Speaking in a near-monotone,

day in 2016, more than double the statistic from five years

Mike relates the thefts from family, friends, and strangers

before.

to feed his addiction, and speaks of a felony conviction that

"That just blows my mind," continues Mike. "When other

led to his imprisonment while his grandfather, the man he

states and other countries are proving that therapeutic

most looked up to, was dying. Juxtaposed with recollections

communities-giving a convict, a felon, an addict, purpose

from Mike's mother, who vowed never to give up on him,

to do better, giving them training, giving them their

we hear how Mike spent three days on life support in a

responsibility back, letting them get their life back on their

Bangor emergency room, having been pronounced dead

own, they're earning it-works."

of an overdose, then revived. Most importantly, the film

Rather than criminalization, Mike adds, "if we humanize

chronicles Mike's recovery through the reentry center and

addicts, if we give them their own voice, we can solve the

the Restorative Justice Project. He now seeks to help young

crisis."

people avoid self-destruction.

Thanks to Mike, notes Ursa, "you don't simply get to

His voice intensifying just a bit, Mike says, "Do you

know a recovering addict. You get to know a person. There's

realize that right now, there are only ten detox beds in the

a line near the end of the film that I think illustrates this.

whole State of Maine? Do you realize right now there are

While discussing how he's doing now, Mike says, 'Today my

only thirty male community-status reentry beds?" This,

days are really good. Every addict has setbacks, just like

when Maine suffered more than one drug overdose death a

everybody I guess." - -Donna Gold

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

25

(IIII

(IIII

(IIII

(IIII

Viewer Controls

Toggle Page Navigator

P

Toggle Hotspots

H

Toggle Readerview