From collection Jesup Library Maine Vertical File

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Search

results in pages

Metadata

An Island In Time: Three Thousand Years of Cultural Exchange on Mount Desert Island

THE ROBERT ABBE MUSEUM

Bar Harbor, Maine

1989

BULLETIN XII

An Island in Time

Three Thousand Years of Cultural

Exchange on Mount Desert Island

Jesup Memerial Library

34 Mt. Decent at

Bar Harber, ME 04809

Cover Design by Cathy Brann

Photography and Graphics by Stephen Bicknell

Copyright © 1989 by The Robert Abbe Museum.

All rights to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, reserved.

375

THE ROBERT ABBE MUSEUM

Bar Harbor, Maine

1989

BULLETIN XII

An Island in Time

Three Thousand Years of Cultural

Exchange on Mount Desert Island

Essays by

David Sanger and Harald E. L. Prins

Edited by

Ann McMullen and Diane Kopec

Introduction

"An Island in Time: Three Thousand Years of Cultural Exchange

on Mount Desert Island" is both an exhibition and a publication. The

exhibition, made possible by a major grant from the Maine

Humanities Council and awards from the Elizabeth B. Noyce Fund of

the Maine Community Foundation and the Atwater Kent

Foundation, opens at the Abbe Museum, Bar Harbor, in May of 1989

and at the Hudson Museum, University of Maine, Orono, in

December of 1989.

The exhibition explores Native American cultural continuity and

change on the central Maine coast, focusing on Mount Desert Island.

Using Indian artifacts, a wigwam representation, artifacts from Jesuit

missions, maps and illustrations, and insights from the disciplines of

archaeology, anthropology, history, and ethnohistory, the exhibition

investigates the interactions, perceptions, and exchanges between

Native American and European cultures, especially the French and

English.

This publication accompanies the exhibition, but is also meant to

provide the public with a prehistoric and historic account of the Native

Americans of Mount Desert Island, from 3,000 years ago through the

time of exploration and settlement by Europeans. It complements the

exhibition by expanding upon its theme and fills a gap in the literature

on the Indians of Mount Desert Island and the Contact period.

The first essay, by Dr. David Sanger, focuses on Mount Desert

Island's prehistoric populations, in particular, those living at the

Fernald Point site. In "Insights into Native American Life at Fernald

Point," Dr. Sanger sets the stage by providing an overview of the

environment and food resources available to the Indians at Fernald

Point. He presents a picture of pre-European life on Mount Desert

Island, describing the tools, their uses and native methods of procuring

food, as well as examining the question of site seasonality. Dr. Sanger

ends this wonderful picture of early life on Mount Desert Island with a

word of caution about sites at risk due to continuing coastal erosion.

Dr. David Sanger, Professor of Anthropology and Quaternary

Studies at the University of Maine. Orono, has conducted prehistoric

archaeological research in British Columbia, the northwestern United

States, the Canadian Maritimes and the northeastern United States.

His research has focused on paleo-environmental archaeology and

prehistoric adaptations to maritime environments. An area of special

interest to Dr. Sanger is the central Maine coast, which includes

1

Mount Desert Island. Dr. Sanger excavated the Fernald Point site for

the National Park Service in 1975 and 1976, thus providing us with an

intimate look at early life on Mount Desert Island.

Dr. Harald Prins' essay, "Natives and Newcomers: Mount

Desert Island in the Age of Exploration," begins with the arrival of the

first Europeans in Maine. He looks at the early European

explorations, trade, and settlement, including the establishment of

Saint Sauveur mission, the first Jesuit mission in North America. Dr.

Prins also explains some of the complexities of determining which

Indian tribes lived on Mount Desert Island, a question frequently

asked by Museum visitors. His essay looks at the time of exploration

from the European as well as the Native American perspective, a

balance not frequently expressed in the literature.

Dr. Harald Prins, currently Assistant Professor of Anthropology

at Colby College in Waterville, Maine, has conducted ethnographic,

historical, and archaeological research in Argentina, The Netherlands,

Israel, and North America. His current research is on the history of the

Wabanaki culture area Indian-European relations, and Native rights

issues in the U.S.A. and Canada. He works closely with the Aroostook

Band of Micmac Indians and various other American Indian groups as

a consulting anthropologist and, in 1985, produced "Our Lives in Our

Hands," a documentary film on Micmac basketmakers in northern

Maine. His expertise in Indian-European relations is well suited to

increasing our understanding of the Contact period on Mount Desert

Island.

I would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge and thank

the many institutions and individuals whose participation made this

project a success. The Hudson Museum, University of Maine, Orono,

cosponsored the exhibition. Lenders to the exhibition include Acadia

National Park, Fort Western Museum, the Maine Historical Society,

the Maine State Museum, the Southwest Harbor Library, and the

Anthropology Department of the University of Maine, Orono.

Without their cooperation, the exhibition would not have been

possible.

Dr. David Sanger, Dr. Harald Prins, and Ruth Whitehead,

Curator of the Nova Scotia Museum, were project scholars. Ann

McMullen, Anthropology Department of Brown University, curated

the exhibition and Cathy Brann, Hudson Museum Graphic Artist,

produced graphics and designed the exhibition. Steven Bicknell,

Archaeology Laboratory Technician at the University of Maine,

Orono, led the construction of the wigwam, produced graphics and

maps, and photographed artifacts for the exhibition and publication.

2

I would also like to thank Dr. Richard Emerick, Joan Klussmann,

and Gretchen Faulkner, Hudson Museum; Jack Hauptman, Deborah

Wade, Meg Fernald and Ed King, Acadia National Park, National

Park Service, Bar Harbor; Paul Rivard, Dr. Bruce Bourque,

Madeleine Fang, Allyson Humphrey, and Robert Lewis, Maine State

Museum, Augusta; Elizabeth Miller, Maine Historical Society,

Portland; Richard D'Abate and Dorothy Schwartz, Maine

Humanities Council, Portland; Jeffrey Zimmerman and Jay Adams,

Fort Western Museum, Augusta; Theodore Mitchell, Office of Indian

Programs and Minority Services, University of Maine, Orono; Robert

Chute, Bates College, Lewiston; Judith Cooper, Center for the Study

of the First Americans, University of Maine, Orono; Pauleena Seeber,

Glenburn; Charles Paquin, Archaeology Research Center at the

University of Maine, Farmington; Jeffrey Kalin, Primitive

Technologies, Inc., Bethlehem, Connecticut; Mark Mowatt, World

Fur Corporation, Brewer; Russ Hewitt, Pride Manufacturing

Company, Guilford; William Belcher, Quaternary Department,

University of Maine, Orono; Suzanne Nash, Hulls Cove; Carole Beal,

Bar Harbor; Betts Swanton, Bar Harbor; George Vose, Jackson

Laboratory, Bar Harbor; Maine State Library, Augusta; Lee

Cranmer, Maine Historic Preservation Commission, Augusta; Dr.

Susan Kaplan, Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College,

Brunswick; Susan Danforth and the John Carter Brown Library,

Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island; The Public Archives of

Canada, Ottawa; Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and

Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma; and the Kendall Whaling Museum, Sharon,

Massachusetts.

The long list of participants is proof of the truly inter-

organizational nature of the exhibition project. Thanks to all of the

individuals and organizations who helped bring "An Island in Time"

to the public.

Diane Kopec, Director

Abbe Museum

3

Insights Into Native American Life

at Fernald Point

David Sanger

"And on your left you see archaeologists

" blared the

loudspeaker from the cruise boat carrying another group of summer

visitors up beautiful Somes Sound (see Figure1). It was July 1977, and

a crew of six archaeologists from the University of Maine diligently

excavated an important American Indian campsite-the Fernald

Point site. By now the crew was almost oblivious to the boat traffic

that monitored their activities.

The Fernald Point story began thousands of years before, when

Native Americans first selected this strategic point for a camping

place. It had everything they needed-a gentle beach for landing

canoes, with a soft bottom that would not damage the birchbark skin,

and vast quantities of soft-shell clams. No one would go hungry as long

as the clams held out. Coming in over the mudflat with every tide there

would be sculpin and flounder, which a simple brush weir could entrap

as the tide fell. The beach faced south SO that even on the coldest winter

day sun would shine right into camp, while behind was a forested hill

that protected the village from bitter north winds. Fish and seals

passed by the front door on their way up and down Somes Sound. Yes,

this was an ideal spot, perhaps a little exposed to swells, but not too

bad at all. And just look at the beautiful surroundings: trees coming

right down to the water's edge everywhere, and hills rising up behind.

Some things have stayed the same, but others have changed since

people first lived at Fernald Point about 1000 B.C. Should one of the

original Fernald Point inhabitants revisit the area, he or she would

notice some remarkable differences. Most notably, one suspects,

would be changes in landscape and land-use patterns. To make the

nineteenth-century farm fields, trees were cut down, and later summer

cottages began to dot the shoreline.

Other changes have occurred. The form of the beach gradually

changed in response to a rise in sea level of over six feet since 1000 B.C.

As the high water mark came up, erosion cut into the beach and

washed away the soft, muddy sediments of the mudflat, leaving

pebbles and stones that could resist better the ebb and flow of the tide.

Through time, then, the constantly rising sea level altered many of

those characteristics that had made the site attractive to the Indians in

the first place. Ironically, the gently sloping beach, that initially proved

ideal for small boat launching and landing, as well as an excellent clam

5

N

Frenchman

Mount

Bay

Desert

bood

Bar Harbor

Island

Fernald Point

Southwest

Northeast

Harbor

Harbor

0

kin

O

5

Figure 1 - Mount Desert Island and the Fernald Point site.

6

habitat, proved to be the cause of the site's abandonment shortly

before the arrival of the strangers from Europe.

In the early 1970s, the deteriorating situation at Fernald Point

and at other archaeological sites in Acadia National Park was brought

to the attention of park officials; because of Native Americans'

tendency to locate sites on soft terrain where mudflats are found,

natural destruction of sites was commonplace. And, though every

National Park wants to protect its historical and archaeological

resources, the Park Superintendent lacked the funds to even begin to

determine the extent of the problem-an archaeological site survey to

assess the resource and its condition.

After a period of frustration, a short note to Washington brought

about instant results: a small contract between the Park Service and

the University of Maine to conduct a systematic survey of the

shorelines in Acadia National Park. The report of this initial survey

noted a number of sites, discussed their condition, and made

recommendations. One site emerged as extremely important-the

Fernald Point site. Not only was erosion taking a toll, but the exposed

bank had encouraged people to dig into the site to recover artifacts for

private collections, an activity which was, of course, illegal. In keeping

with its significance, the site was placed on the National Register of

Historic Places.

Having identified the problem, money was again a difficulty.

Some funds dedicated for "ruins stabilization" work materialized, and

a plan was drawn up to conduct a limited excavation, especially in the

area most affected by the sea erosion and public looting. To further

protect the site, boulders would be placed along the front of the site to

help inhibit erosion.

Based on some 1976 testing, research assistant Barbara Johnson

and David Sanger made plans for the 1977 season. Johnson would

take a crew of seven experienced excavators to Fernald Point for six

weeks; the crew would test the eroding front of the site, as well as parts

of the site further back in the field. Large scale excavations, however

desirable, were out of the question; there simply were not enough

funds to do a thorough job.

As the site map shows (see Figure 2), we concentrated our

activities largely along the eroding front of the site. Excavation

proceded by hand-held trowels and all site deposits were screened

through 1/4-inch mesh (see Figure 3). In this way, very small bones

and artifacts the excavator might miss could be recovered.

7

Fernald Point Site

20

Housepit

Beach

III

1976 Excavation Unit

1977 Excavation Unit

cm

O

5

C.I. 0.25m

Figure 2 - Site map showing 1976 and 1977 excavations.

Figure 3 - Overview of the Fernald Point site during 1977 excavation.

8

Excavation destroys a site, no matter how carefully the work is

done. Because of this, it is imperative that maximum attention be paid

to documentation through field notes, drawings, and photographs.

We cannot, of course, record everything; some compromises must

occur if we are to excavate enough of the site to make any statements

about the people who lived there. Then, too, continued site erosion

creates a sense of urgency.

The Fernald Point site was a large shell midden. The term

"midden" comes from a Scandinavian word that refers to kitchen

wastes. Shell midden, then, refers to the leavings of people who lived at

a site and deposited their kitchen trash, shells, bones, broken

implements, and the like. For the archaeologist this is a gold mine of

information. In the absence of written records, this is all we have to

reconstruct past lifeways.

There is an added bonus to excavating shell middens as opposed

to sites in the wooded interior of Maine. Maine soils are normally

acidic. In such environments bones rapidly decay, with the result that

most interior sites rarely have much preserved evidence for the animals

people ate. Shell middens, by contrast, result in excellent preservation

because the shells, being composed largely of calcium carbonate,

neutralize the normal soil acidity, resulting in better preservation of

bone and other organic materials.

From our excavations at Fernald Point, and with information

from other sites in the region, we can begin to present a picture of pre-

European life on Mount Desert Island.

Often the questions most commonly asked of an archaeologist are

the most difficult to answer: "What tribe lived here?" During historic

times, the period after about A.D. 1600 for which we have the written

records of Champlain and other explorers, the Mount Desert Island

area was inhabited by people whose descendants now focus on Indian

Island, home of the Penobscot Nation. But when we get back into

prehistory, before written records, we depend on oral traditions

supplemented by archaeology. It is quite possible that ancestors of the

modern Penobscot lived at places like Fernald Point for millennia

before the arrival of the Europeans.

A second question, as perplexing as the first, is "How many

people lived at this site?" Once again we have to equivocate. In the first

place we don't know the full size of the site. While we can get an idea of

how large it is today, who can say how much has eroded away through

time? And, to further complicate matters, just because a campground

can accommodate fifty tents does not mean that fifty tents were always

9

pitched. My guess would be that the size of the population varied

through time, and even in any one year people might come and go.

Somewhere between twenty-five and fifty residents at one time would

be a reasonable guess.

A third important question is, "When did they live here?" Since

the late 1950s, archaeologists have made excellent use of the

radiocarbon dating technique, which measures the amount of carbon-

14, a radioactive isotope of carbon that is a constant value in all living

plant matter, but decays after the plant dies. By measuring the amount

of carbon-14 in a sample of wood or charcoal from a site, an estimate

of the death date of the tree is made. At Fernald Point we obtained

dates ranging from a little over 2,000 to about 700 years ago. However,

based on the similarities between some tools found at Fernald and at

other nearby sites, we place the date of the first occupation at around

1000 B.C. From A.D. 1 until about A.D. 1300 the site was utilized

quite heavily.

The inhabitants of Fernald Point were what archaeologists call

"hunters and gatherers," meaning that they did not practice

agriculture as far as we know. In Champlain's time, agriculture had

spread up the coast to the mouth of the Saco River, and perhaps even

to the Kennebec River, although the evidence is not clear. Even in

southern New England, the growing of corn (maize), beans, and

squash was a relatively recent development, not much older than A.D.

1000, according to recent archaeological evidence.

Buried in the various shell layers at Fernald Point are bones of sea

and land mammals, birds, and fish. Not represented, perhaps due to

preservation factors, were the results of gathering wild vegetable

foods, like berries, roots, and nuts. Simply because evidence of these

foods is not present does not mean that they were not consumed. We

assume that they were part of the diet of the Fernald Point people.

An examination of the bones and shells from Fernald Point

indicates a diet that balanced land and sea species (see Figure 4).

Shellfish remains are mostly of the soft-shell clam, found everywhere

on the central and northern Maine coast. Blue mussels were taken

from their perch on rocks and ledges, and would have constituted a

readily available and predictable resource available at any time of

year. As in some other societies, shellfish gathering may have been a

task taken on by women and children while the men were hunting. The

clams were probably opened by steaming them on the rock hearths we

found at the site; there are few signs of damage to shells resulting from

deliberate breakage. While most shellfish were probably eaten almost

10

Mammals

Birds

Fish

White-tail deer

Great auk

Winter flounder

Moose

Greater scaup

Longhorn sculpin

Harbor seal

Common eider

Atlantic cod

Black bear

White-winged

Wolffish

Sea mink

scoter

Striped bass

Gray seal

Black duck

Dogfish

Beaver

Canada goose

Haddock

Muskrat

Common merganser

Tomcod

Hare

Double-crested

Ocean Pout

Porcupine

merganser

Sea Raven

Raccoon

Great blue heron

Alewife

Gray fox

Grebe

Sturgeon

River otter

Old squaw

Soft-shell clams

Porpoise

Owl

Blue mussels

Dog

Hawk

Sea urchins

Eastern cottontail

Bald eagle

Whelks

Note: these animals are not listed in order of importance.

Figure 4 - List of animal remains found at the Fernald Point site.

immediately, some may have been dried for future use, although there

is no evidence for that practice in the archaeological record.

Other harvests from the sea included fish of several species.

Altogether, the excavation team recovered over 14,000 fish bones,

mostly sculpin and flounder which feed on the mudflats at high tide.

The retrieval of fish from brush weirs set into the mudflat at the front

of the site might also have been the task of women as they dug clams.

Cod, a deeper-water fish sometimes found in Maine coastal sites, were

infrequent at Fernald Point. Sea urchins and other delicacies were also

taken by the local inhabitants. Strangely, they seem to have avoided

lobsters; we have found only one claw in twenty years of excavation in

coastal Maine sites.

The sea also provided seals and a few porpoises. Whaling was not

practiced. Birds, while not common, are mostly sea-oriented species,

such as eiders and great auk.

From the land, the hunters brought home white-tail deer, bear,

and an occasional moose. Beaver remains were quite common at the

Fernald Point site, although muskrat were rare, probably due to the

lack of a suitable local habitat. The remains of sea mink, an extinct

species about the size of a small cat, were also present at Fernald Point.

11

Very few of the bones from the site exhibit any evidence of burning,

which suggests that food was most likely boiled in clay pots or cooked

by steam generated in the numerous stone hearths, much like a

traditional Down East clambake. The bones themselves were split and

cooked for their marrow content, which would have been an

important component of the diet, especially in cold weather.

The artifacts found at the Fernald Point site provide some clues as

to how these various food sources were procured. There are a number

of arrow or spear heads chipped from stone available along the

beaches of the area, or from local outcrops of volcanic rock (see Figure

5). The forms and sizes of these tools changed through time, from

larger to smaller, including different bases, which provided a means to

lash the arrowhead to a shaft. These changes were not random; at

certain times in the past people made their arrowheads within

a

particular range of variation. Understanding how tool types changed

through time helps us to estimate the age of a particular deposit.

We do not think the forms of tools necessarily changed because of

increased technological efficiency, any more than clothing styles

change today as a measure of efficiency.

Another artifact type made of chipped stone is a tool that

probably functioned as a knife (see Figure 5). Archaeologists often call

these tools bifaces because they are worked on both faces or sides.

Some artifacts put in this category may actually represent lost or

damaged items that were intended to have been arrowheads.

Scrapers are common at Fernald Point (see Figure 6). We think

these tools functioned to scrape away fat from the inside of hides,

although they could have been used for other tasks as well. Scrapers

are usually made by removing flakes from only one side of a larger

stone flake. While many of the rocks could be gathered locally, some

rocks probably came from across the Gulf of Maine in Nova Scotia.

Woodworking would have been an important component of

camp activities at Fernald Point. While the wood has long since

deteriorated, we did find stone axe and adze blades, as well as the lower

incisors of beaver, used to carve wood, much like a modern crooked

knife.

Metal was rarely used prehistorically. At Fernald Point, the only

examples are a few awls made of naturally-occurring copper which

was cold-hammered and folded to shape rather than smelted (see

Figure 7).

Animal bone constituted a useful raw material for tools (see

Figure 8). Shaped and polished long bones could be used for awls,

needles, harpoons, and spears. Small bone points might have formed

barbs on wooden hooks for line fishing.

12

IMA

....

cm

in

Figure 5 - Spear heads and knives.

Figure 6 - Scrapers.

cm

in

13

cm

in

Figure 7 - Copper awls.

Figure 8 - Various tools made from bone: awl, barbed and unbarbed points,

and beaver incisors (left to right).

cm

in

14

Containers for food, water, and possessions are always needed

around the home and camp site. Starting around 500 B.C. the Indians

of Maine began making clay pots, after the fashion of peoples to the

south and west. While there were no complete pots found at the

Fernald Point site, there are numerous fragments, or sherds, that span

the range from the earliest vessels used in Maine through later

prehistoric types.

The vessels were made of locally available clay (actually a silt laid

down by higher sea levels 12,000 years ago), mixed with gravel and

coarse sand, called temper, which later gave way to crushed shell

temper after about A.D. 1000. The conical pots were usually built up

by coils, smoothed, decorated, and then fired in an open fire hearth.

The resulting vessels were unglazed and porous until coated on the

inside with accumulated fat from cooking (see Figure 9).

The majority of pots were decorated before firing. Initially,

designs were made with a small carved wooden or bone stamp that left

tooth-like impressions on the vessel; these are known as "dentate

stamped" pots. Sometime around A.D. 1000 a new technique became

common in the Northeast and vessels were decorated by a stamp made

of a cord or string wrapped around a stick or paddle. Archaeologists

call these "cord-wrapped stick" ceramics. Like the arrowheads, styles

in decoration changed through time. However, the plastic nature of

clay lends itself to manipulations that leave much better traces of style.

Archaeologists in Maine can now gauge the age of a vessel to within a

two- or three-hundred-year period. In other parts of the world it is

possible to estimate the age of a site much more accurately, within

decades, with the aid of pottery. While we refer to the markings on

pottery as "decoration," this might not have been in the mind of the

maker. He, or more likely she, may have labelled the pot with the

insignia, or crest, of her family, clan, or tribe.

Our excavations at Fernald Point located one definite house and

possibly another. The nearly intact house had been partially destroyed

by erosion. Although we did not excavate all of the remaining portions

of the house due to time restrictions, we were able to recover some

information on its size and shape. In all respects it resembled many

other houses our crews have excavated on the Maine coast. The typical

house was oval, about eight to twelve feet long by eight to ten feet wide,

for a floor area of less than one hundred square feet. The shape was

always oval. Depending on the period, the house might rest on the

surface or it may have been dug into the soil or into an older midden

deposit, SO that up to two feet could be below ground level. A number

of poles, resting on the outside of the house depression, provided the

15

Figure 9 - Reconstruction of clay pot. Design by David Putnam. From

Maine Archaeological Society Bulletin, Spring 1986, Volume 26, Number 1.

16

supports for a conical covering, probably of birchbark. Sometimes

rocks were used to help support the poles. Inside there was a hearth,

usually situated towards one end of the house near the entrance.

In excavations we frequently recognize housepits by layers of

midden that are relatively shell-free. These shell-free strata appear to

be the result of sand and gravel brought up from the beach and strewn

over the floor to form a clean, smooth surface (see Figure 10). With

time these floors got dirty from household activities and another layer

of clean sand was brought in. Eventually, the house depression was

filled up.

Whether each floor represents one season or less is not clear. At

Fernald Point the house seems to have been utilized around A.D. 800

and again at A.D. 1200, based on radiocarbon dates and the kinds of

pottery found. The evidence suggests that the later group, seeing a

ready-made cellar, moved right in.

495 50E

49S52E

49S54E

Column 5

VI

Central

Hearth

VII

VII

cm

Rock

Sod

Loam

Shell

IV

Gravel

V

Charcoal Stained Gravel House Floor

VI

Ash

VII

Subsoil

Figure 10 - Stratigraphy of housepit 1 showing charcoal stained gravel floor.

Another clue to the presence of a house floor is an increase in the

number of artifacts and rejected raw materials, indicative of

manufacturing taking place in the house. Summer houses may have

many fewer artifacts inside, as the better weather would encourage

outdoor work. In the Fernald Point house we found a number of

specimens in the house deposits.

Houses tended to be built toward the back of a site, away from the

beach, while the midden or dumping area developed by the beach.

Because we were concerned with the erosion problem and the front of

the site, we did not uncover additional houses. Information from other

similar sites suggests that settlements of this period contained a

number of houses rather than just one.

17

In prehistoric times, people living on the coast of Maine had to

have water transportation. Unfortunately, physical evidence for boats

is extremely rare in the archaeological record. Historically, the

birchbark canoe was ubiquitous in Maine. This lightweight, yet highly

seaworthy craft, was capable of making substantial journeys. Ocean-

going canoes, up to 25 feet in length, were in common usage during

historic times. Because we find sites that are up to 5,000 years old on

the outermost islands, we know canoe travel has had a long history in

the Maine area.

One of the prominent questions in Maine prehistory has been the

matter of seasonality: what time of the year did Indians spend in their

coastal settlements? It has been said that the Indians spent their

summers on the coast and retired during the winter to traditional

hunting and trapping grounds in the interior. However, such a pattern

seems to have been prevalent only after the arrival of Europeans.

Archaeological evidence indicates possible year-round settlement in

coastal environments, but not necessarily at one site.

This evidence comes from two related sources. One source is

provided by the presence or absence of seasonally specific animals. For

example, some birds are winter residents on the coast, others are

summer, and still others are migratory. The identification of bird

remains helps to determine when particular activities took place at the

site. Fish may go through migratory patterns, as may marine

mammals.

A second source of information comes from changes that resident

species undergo through the year. Mammals, for example, develop

annual growth layers on their teeth. When the teeth are cut open and

examined, an estimate of seasonality can be obtained. Male deer drop

their antlers in the winter. Therefore, a skull of an adult male deer with

evidence that the antlers have dropped naturally indicates a winter kill.

Clams have an annual growth cycle followed by a period of quiescence,

much like a tree ring. Because they are SO common in shell middens, we

can examine hundreds of shells to find out what season the clams were

dug. If we assume that the season of procurement was also the time of

living at the site, then we have a useful method of determining site

seasonality.

The evidence indicates that the Fernald Point site was used both

in warm and cold seasons, but that does not mean it was used year-

round. Summer occupation could have been followed by occasional

winter use. At this time, too little of the site has been excavated to

allow us to make any more definitive statements, although evidence

from the house at Fernald Point almost certainly refers to a winter

occupation.

18

Of the ceremonial or religious way of life at Fernald Point we

know comparatively little. The site is, of course, a habitation and we

should not expect to find much evidence for the spiritual side of life.

Our excavations did encounter a group of four burials at the eroding

bank edge. It is clear that they were carefully placed into the midden,

but few artifacts accompanied the remains. The graves may be

unrelated to the other findings at Fernald Point, and represent the

deceased of another group. The burial took place around A.D. 1100;

midden burial is generally rare in Maine.

It would be a mistake to think of the Fernald Point people as

living in a social vacuum. The presence of artifacts made from rocks

thought to be from Nova Scotia indicates contacts across the Gulf of

Maine in prehistoric times. Evidence from recent excavations near

Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, hints that journeys across the one hundred

miles of open water to Yarmouth had been going on since 2,000 B.C.

If there was a year-round presence of people on the coast of

Maine, then the many sites in the interior suggest a resident,

permanent, interior population. Undoubtedly, there was

intermarriage with the interior groups as well. The Penobscot speak of

inland and water clans, or family groups, a clear suggestion that people

of a single ethnic identity occupied both coastal and interior terrain.

Intermarriage between clans would establish in-laws in both areas,

always a useful relationship in a land where resources might vary.

Over the years, speculative literature about pre-Columbian

European voyagers to the coast of Maine has become popular.

However common, these claims lack any evidence to convince

professional archaeologists of such travels.

There is much more we would like to know about Fernald Point

and the people who lived there off and on for over 2,000 years. Some of

this information is irretrievable because it has been eroded away by the

effects of sea-level rise in the area.

What is the potential for the Fernald Point site to yield additional

secrets? The seawall put in place in 1977 has stood up very well, and did

yeoman service during the big storm in the winter of 1978. There are

signs, however, that the boulders may be losing some of their

effectiveness, and that erosion will again become a factor. Our efforts

recovered information that would otherwise have been lost many years

ago. It remains to be seen, however, whether we can respond when the

inevitable reoccurs, and the Fernald Point site is again at risk.

19

Natives and Newcomers

Mount Desert Island

In The Age Of Exploration

Harald E. L. Prins

What Happened In Maine Indian History?

In the late nineteenth century, only a few Penobscot elders could

still recount the myths, legends, and stories of events long past. The

traditions and collective memory of Maine's tribespeople were held in

these oral tellings; without them, the native legacy would be lost. In

1893, trying to preserve his tribal heritage, Joseph Nicolar recorded

these oral traditions "handed down from the beginning of the red

man's world to the present time."

In contrast to accepted anthropological theory which states that

Maine's contemporary tribespeople descend from PaleoIndian big-

game hunters who migrated from Siberia some fourteen thousand

years ago, native tradition holds that Gluskap, the first human, came

into being "when the world contained no other man, in flesh, but

himself." According to Nicolar's narrative, The Life and Traditions of

the Red Man, this creation took place in northeastern North America.

Since that primeval time, native people inhabited these lands,

following the teachings of Gluskap, their culture hero. Finally, after a

long, long time, the first Europeans arrived on their shores. This is how

tribal historians remembered the event:

some young men were out on a hunt, and according to

custom had taken one old man with them, and on coming

out to the seashore in a little cove where a small brook came

out to the sea, the young men discovered a man's track upon

the high land, the track begun from the shore and back to it,

and around the brook of the fresh water, which appeared to

them that someone had been carrying water from the brook

to the salt water shore, but no canoe of any kind could be

seen moving as far as they could see. When this news was

brought to the old man he at once proposed to investigate

the matter

and upon comparing the strange tracks to

those they made, there was a vast difference in three ways,

first the person that made the strange tracks must have had

on moccasins made of hard substance; second, the tracks

were larger than theirs; third, and the most strange part of

21

all, the toes pointed outward instead of inward like those

they made themselves. Upon arriving at a conclusion, that

the tracks were made by a strange person, it SO affected the

old man that he shed tears

The tradition may refer to the first encounter between native

people and Basque whalers, or Portuguese or French Breton cod

fishermen, who frequented the southern coasts of the Gulf of Saint

Lawrence from the early 1500s onwards. More probably, it refers to

the landing of Giovanni da Verrazano in the Penobscot Bay area in

1524. This Italian explorer, resident of the French port of Rouen, left a

written report of such an encounter. In his high-minded estimation,

the coast of Maine was inhabited by

Bad People

of rude and bad habits, SO barbarous

that we could converse with them only by signs. They dress

in skins of bears, wolves, seals, and other animals. Their

food, insofar as we learned by going through their

habitations is game, fish, and a kind of wild root.

Another likely candidate for the "strange person" described in

Penobscot oral tradition is the Portuguese pilot Don Estevan Gomez,

commander of the fifty-ton caravel La Anunciada. Sailing in the

service of the Spanish Emperor Charles V, he explored and mapped

the coast from Cape Breton south-westward, rounding Mount Desert

Island, and entering the Penobscot River in the winter of 1525.

Several other European navigators sailed the Gulf of Maine in the

sixteenth century, some claiming to have steered their ships upriver.

One account, written by Andre Thevet, noted that a French crew had

traveled "about ten leagues" up the Penobscot in 1556, where they

founded a small fort, called Norumbega. Later, in 1580, an English

expedition under John Walker landed at "the River of Norambega"

(Penobscot?), where they happened on an Indian lodge filled with

three hundred moose hides. Helping themselves to the bounty, they

sailed back to England. That same year, the Portuguese pilot Simon

Ferdinandes, commanding another English vessel, also landed on the

Maine coast, where he and his crew acquired a number of hides. By this

time, it was not uncommon for French and Basque navigators to sail

far up the St. Lawrence River.

Whether the native oral tradition referred to the vessels under

command of Verrazano, Gomez, Walker, or to one of the other early

European mariners that landed on their shores, it is clear that natives

recalled the event with bitterness and sorrow.

22

Identifying Maine Indian Tribes in the Early Contact Period

We are concerned here, in particular, with the history of Mount

Desert Island during the early contact period. An effort to reconstruct

this history elicits several problems, not the least of which is the

inconsistent system of names used to refer to the region's ethnic groups

in the early 1600s. For instance, which particular tribes inhabited the

area? How did the natives live? What was their relationship to their

neighbors? How did they react to the European invasion of their

world? The few existing written records of that period offer us some

insight into the indigenous way of life on Maine's central coast (see

Figure 1).

During the period of culture contact, Maine Indians organized

themselves in ethnic groups, often called tribes. These tribespeople

belonged to different native communities, each having a particular

social identity which allowed them to identify their relationships with

one another: friends, allies, trading partners, foes. Fellow tribespeople

shared certain cultural traditions-a particular way of speaking, a

collective body of religious beliefs and practices, a sense of historical

continuity, and an acknowledged common ancestry or place of origin.

Each of these communities was recognized by its own particular name.

In addition to the name they themselves used, they were often known

by the way neighboring groups referred to them. Typically, these

names alluded to a particular characteristic, such as the type of land

they inhabited, their speech, or particular habits.

Not surprisingly, early European observers of the native scene in

historic America were puzzled about the ethnic composition of local

groups-confused by the effects of movements of native populations,

new village formations, conquests, large-scale adoption, and tribal

name changes. In consequence, the documents are not always

consistent in their description of tribal groups, sometimes using a

variety of names to refer to one and the same group, or vice versa. The

resultant confusion is especially evident in the case of Atlantic coastal

groups such as the Wabanaki, who have had dealings with different

European groups for nearly five hundred years.

With respect to records concerning Maine's various tribal groups

in the early historical period, we are primarily dealing with French and

English traditions. The English typically named indigenous local

groups after their geographic locale, including territories, rivers, lakes,

and bays. The French, however, followed native practice, classifying

native communities on the basis of ethnic or linguistic criteria.

23

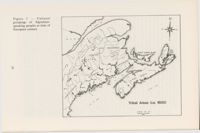

Figure 1 -

Cultural

N

groupings of Algonkian-

speaking peoples at time of

European contact.

W

E

QUEB

E

C

S

NEW

BRUNSWICK

Cape

Breton

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND

Island

Presque

A

N

b

SCOTIA

Old Town

NOVA

Bangor

Port

Royal

Halifax

Grand

THE

SW

Manan

Augusta

Bar

Harbor

OCEAN

N.H.

ATLANTIC

Portland

Tribal Areas (ca. 1600]

0 10 20 30 40

that

Miles

For instance, from the early seventeenth century onwards, French

explorers in the Gulf of Maine, starting with Samuel de Champlain in

1604, identified three major ethnic groups in the Gulf of Maine area,

and referred to them as Souriquois, Etechemin or Etchemin, and

Armouchiquois or Almouchiquois. Operating from their colonial

headquarters at the Bay of Fundy (1604-1613), the Frenchmen

probably adopted the native names used by their local Indian trading

partners. Souriquois (the ancestors of today's Micmac) may have

reference to the fact that they travelled from the Gulf of St. Lawrence

to the Bay of Fundy by way of a river called Souricoua. Etchemin (the

ancestors of today's Maliseet, sometimes spelled Malecite, and

Passamaquoddy) may have derived from cheenum, a Micmac word

for man, or from skijm, a Maliseet word for the same. The

Armouchiquois (the ancestors of today's Abenaki) were a people

considered hostile by Micmac; the name probably derived from the

Micmac word for dogs, used as a derogatory term.

Later, after founding a new colony in the St. Lawrence River

valley, the French in Canada adopted the local Algonkin name for

those they had earlier referred to as Armouchiquois. Inhabiting the

lands from the Kennebec River southwards, these Indians were called

Abenaki-"eastlanders."

In the late 1600s, however, the French colonists in Acadia

(comprising the region from Cape Breton to the Kennebec) adopted

yet another terminology based on information obtained from their

Micmac companions. The name Micmac (probably meaning "Our

kin-friends") took the place of Souriquois. Maliseet ("those who speak

badly") replaced Etchemin. Canibas (referring to the Kennebec)

partially replaced Abenaki. The term Maliseet included those later

distinguished as the Passamaquoddy, who still share the same

language with the Maliseet.

Though distinct in a number of ways, these Northeastern

Algonkians spoke related languages, echoed one another's basic

patterns of culture, and shared equally in the upheaval brought on by

the arrival of the "Strangers." Commenting on the relationship

between these three ethnic groups in the colonial period, a French

Jesuit historian wrote in 1744:

the close union formed between these three nations, their

attachment to our interests and to the Christian religion

have quite commonly led to include them all under the

general name of Abenaqui nations

25

With respect to Mount Desert Island, centrally located on Maine's

coastal travel route, there is evidence that the island was frequented, at

one time or another, by Indians belonging to each of the region's major

three ethnic groups, collectively considered as Wabanaki

("Dawnlanders") since the seventeenth century.

Commerce, Conflict, and Colonialization in the Gulf of Maine

By the 1530s, tribespeople ranging the Gulf of St. Lawrence

region were in regular contact with European fishermen and traders,

exchanging furs and hides for commodities such as steel knives, cloth,

biscuits, and other items. Chieftains of some strategically located

groups of Micmac and Montagnais Indians became middlemen in the

fur trade from the second half of the sixteenth century onwards. By the

1590s, some of these native fur traders had acquired European

shallops; in these small boats they sailed enormous distances in the

pursuit of trade. Before the arrival of French and English fur traders in

the Gulf of Maine, Micmac entrepreneurs monopolized the trade

between the Gulf of St. Lawrence and coastal Maine, where they

purchased the skins of moose, deer, bear, sable, otter, mink, and

especially beaver. In addition, they acquired corn, squash, beans, and

wampum (white and blue shell beads) from the Abenaki and their

southern neighbors.

Until the early 1600s, when European commercial activities

remained confined to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Micmac were

unchallenged as middlemen in the fur trade. This situation changed

when French, Basque, and English vessels ventured into the Gulf of

Maine on a more regular basis (see Figure For instance, in 1602, the

English bark Concord sailed from Cornwall to the Gulf of Maine.

Using a detailed description of Verrazano's 1524 voyage, the crew

under Captain Gosnold "made the land" at Cape Neddick. There, on

the coast of southern Maine, they happened on a Micmac trader.

According to Gosnold's report,

we came to an anchor, where six Indians in a Basque

shallop with mast and sail, an iron grapple, and a kettle of

copper, came boldly aboard us, one of them apparelled with

a waistcoat and breeches of black serge, made after our sea-

fashion, hose and shoes on his feet

These with a piece of

chalk described the coast thereabouts, and could name

Placentia (Plaisance, a popular harbor for European fishing

fleets) of the Newfoundland

26

Et ait Helias Reuertere et africe Septem vicibus, et factum cst in Septima ct cccc nubes parna oves fendchat

Adam Willeres Inuenter

Magdalena Van de pas fecit

pas

Figure 2 - This engraving of Basque whalers shows a number of vessel types

popular during the seventeenth century. The smaller boat in the foreground

may be a shallop, often equipped with both sail and oars. The larger vessels

are probably carracks, typical trading vessels of the fourteenth through

seventeenth centuries. Ships of this type were probably used by the early

explorers and would have become a familiar sight to native people on the

coast. Photo courtesy The Kendall Whaling Museum, Sharon,

Massachusetts, USA, P-S114.

27

In 1604, two French vessels arrived in the Gulf of Maine. The

expedition's navigator, Samuel de Champlain, scouted the area for a

suitable place to locate a new colony and fur trade post, and initially

established one on an island in Passamaquoddy Bay. Guided by two

local Indians, a Micmac and a Maliseet, Champlain and twelve

crewmen boarded a pinnace to explore the coast. On September 5,

Champlain noted in his log:

we passed also near to an island about four or five

leagues long, in the neighborhood of which we just escaped

being lost on a little rock on a level with the water, which

made an opening in our barque near the keel. [This island]

is very high and notched in places, SO that there is the

appearance to one at sea, as of seven or eight mountains

extending along near each other. The summit of most of

them is destitute of trees, as there are only rocks on them

I named it Isle de Monts Deserts.

The Indian name for Mount Desert Island was Pemetiq, meaning "a

range of mountains." They encountered some canoes in the Mount

Desert Island area, manned by Indians who "had come to hunt beaver,

and to catch fish, some of which they gave us" (see Figure 3).

Champlain reported that these people "guided us into their river

Peimtegoet [Penobscot], as they call it, where they told us lived their

great Captain named Bessabez, headman of that river.' Observing that

it "was the first time they had ever beheld [European] Christians,"

Champlain referred to these natives as Etchemins (Maliseet-

Passamaquoddy) and described them as "very swarthy and

clothed

in beaver-skins and other furs."

Searching for the legendary city of Norumbega, Champlain

steered his small vessel far up the Penobscot. Finding no evidence of

this place, he reported seeing

only one or two empty Indians cabins which were

constructed in the same manner as those of the Souriquois

[Micmac], which are covered with tree-bark; and from what

I could judge there are few Indians in this river, which is

called Pemetegoit [Penobscot]. They come there and to the

islands for only a few months in summer during the fishing

and hunting season when game is plentiful. They are a

people

with no fixed abode; for they winter now in one

place, now in another, wherever they perceive that the chase

for wild animals is the best.

28

Figure 3 - Native men fishing in a Micmac-style canoe, early seventeenth

century. From Les Raretes des Indes by Becard de Granville. Photo courtesy

The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

29

The Etchemin chieftain Bessabez, or, as the English referred to him,

the Bashaba, was the powerful sagamore (headman) of about 250

warriors. Politically allied to neighboring sagamores, each of whom

had their own followings, Bessabez was able to muster the support of

many hundreds of fighters. However, he "had many enemies,

especially those to the east and northeast, whom they called Tarantines

[Micmacs, who were] counted a

warlike and hardy people."

The following year, the French colonists, under the Sieur de Monts,

relocated their settlement across the Bay of Fundy, at Port Royal,

while Champlain continued to explore and map the coastal region as

far south as Cape Cod. That same year, five Etchemin were kidnapped

from Pemaquid by an English crew under the command of Captain

Weymouth, who shipped them back to England. They eventually came

into the custody of an entrepreneur named Lord Ferdinando Gorges,

who kept them for several years, and "made them able to set me down

what great rivers ran up into the land, what men of note were seated on

them, what power they were of, how allied, what enemies they had, and

the like

" The captives, Dehanada, Skidwarres, Assacomet,

Maneddo, and Amoret said they came from Mawooshen, a territory

"governed in chief by a principali commander or prince, whom they

call Bashaba [of Penobscot], who hath under his divers petty kings,

which they call sagamores,

all rich in divers kinds of excellent furs."

When Armouchiquois tribesmen from the Saco River murdered a

Micmac trader at Penobscot Bay, Membertou, the Micmac sagamore

at Port Royal, assembled a fighting force of Micmac and Maliseet

allies to revenge his kinsmen (see Figure 4). In the summer of 1607,

armed with spears, tomahawks, bows and arrows, as well as with

muskets, the warriors sailed in shallops to the Saco, where they

attacked the Armouchiquois. It appears that their French allies had

supplied them with the firearms when the French, including

Champlain, temporarily vacated Port Royal, returning to France to

settle some legal disputes about Sieur de Monts' title to the fisheries

and fur trade in Acadia.

Meanwhile, two English vessels, guided by Skidwarres and

Dahanada (two of Weymouth's kidnapped tribesmen), arrived at the

mouth of the Kennebec in 1607, founding the Popham colony.

According to the region's natives their Spirit, Tanto, "commanded

them [the Indians] not to dwell neere, or come among the English,

threatening to kill some and inflict sickness on others, beginning with

two of their Sagamo[re]s children." Unsuccessfully settled by a group

of "convicted felons," the Popham colony was abandoned in 1608.

30

marvelled at native dress and decoration, including here tattoos and what

Figure

4 - Seventeenth-century Micmac man. Early explorers often

may be a wampum or glass bead headdress. Engraving by J. Laroque, after

Jacques Grasset St. Sauveur. Photo courtesy Public Archives of Canada, C-

21112.

31

The following year, the Dutch vessel De Halve Maen (The Half

Moon) under Captain Henry Hudson arrived in the Gulf of Maine. En

route to the Penobscot River, he and his crew spotted several French

fishing vessels and two sailing boats manned by Micmac. The Indians

informed Hudson that "the Frenchmen doe trade with them; which is

very likely, for one of them spoke some words of French." Landing at

Penobscot, they saw

two French shallops full of the country people [Indians]

come into the harbour, but they offered us no wrong, seeing

we stood upon our guard. They brought many beaver

skinnes and other fine furres, which they would have

changed for redde gowns. For the French trade with them

for red cassockes [coats], knives, hatchets, copper kettles,

trevits [?], beades, and other trifles.

After five days of trade Hudson's men switched their tactics to force,

driving the natives from their houses and seizing the furs they wanted.

Leaving the Penobscot behind, the Dutch sailed for the Hudson River,

named after De Halve Maen's savage captain.

The Founding and Fall of the Jesuit Mission at Mount Desert Island

By this time, crews from several French and English vessels were

employed in fishing and fur trade activities all along the coast, called

Acadia by the French. Concerned about the increased competition for

beaver and other furs in the Gulf of Maine area, a party of about

twenty French colonists returned to Port Royal in 1610. For three

years, the abandoned establishment had been guarded by Chief

Membertou and the Micmac. In addition to the Sieur de Poutrincourt,

their commander, and his son de Biencourt, the community at Port

Royal included secular priest Jesse Fleché, who immediately began to

baptize the local Micmac, although "he did not know the language,

and had nothing with which to support them."

In May 1611, after four months at sea, two Jesuit Fathers, Pierre

Biard and Enemond Massé, arrived in Port Royal on board La Grace

de Dieu. They were sponsored by the powerful Marquise de

Guercheville, wife of the Governor of Paris and lady-in-waiting to the

Queen Mother, Marie de Medici. During the summer, Biard

accompanied Biencourt on several trips, "the one lasting about twelve

days, the other a month and a half; and we have ranged the entire coast

from Port Royal to Kinibequi [Kennebec]

We entered the great

32

rivers St. John, Saincte Croix, Pentegoet [Penobscot], and the above-

named Kinibequi

We visited the French who have wintered there

this year in two places, at the St. John River and at the river Saincte

Croix." During his journey to Penobscot River, Biard visited

Bessabez's village:

"

there was the finest assemblage of Indians that I

have yet seen. There were 80 canoes and a shallop, 18 lodges and about

300 souls."

In exchange for furs, the region's tribespeople acquired all kinds

of European commodities, such as steel knives, hatchets, copper

kettles, alcohol, and cloth, among other things. The impact of the fur

trade on Wabanaki life was quite obvious, as Biard noted: "

in

Summer they often wear our capes, and in Winter our bed-blankets,

which they improve with trimming and wear double. They are also

quite willing to make use of our hats, shoes, caps, woolens and shirts,

and of our linen to clean their infants, for we trade them all these

commodities for their furs."

From Port Royal, Biard mailed detailed reports to his superiors

in Paris, describing the conditions in Acadia, its native peoples, their

way of life, and, of course, the commercial opportunities of the fur

trade and the fisheries. Commenting on his mission to the Indians, the

Jesuit wrote:

If they are savages, it is to domesticate and civilize them that

we have come here; if they are rude, that is no reason that we

should be idle; if they have until now profited little, it is no

wonder, for it would be too much to expect fruit from this

grafting, and to demand reason and beard [maturity] from a

child.

On the other hand, the Jesuit was quite aware how the region's

Wabanaki viewed the Europeans on their shores:

[They] conclude generally that they are superior to all

Christians

Also they consider themselves more

ingenious, inasmuch as they see us admire some of their

productions as the work of people SO rude and ignorant;

lacking intelligence, they bestow very little admiration upon

what we show them, although much more worthy of being

admired. Hence they regard themselves as much richer than

we are, although they are poor and wretched in the extreme

They consider themselves better than the French: 'For,

they say, 'you are always fighting and quarreling among

33

yourselves; we live peaceably. You are envious and are all

the time slandering each other; you are thieves and

deceivers; you are covetous, and are neither generous nor

kind; as for us, if we have a morsel of bread we share it with

our neighbor, they are saying these and like things

continually

Supported by the Queen Mother, influential Jesuits in Paris

induced Madame de Guercheville to form a new French colony in

Acadia. Having acquired a grant from King Louis XIII, she possessed

a monopoly on the fur trade in the Gulf of Maine. Madame de

Guercheville appointed the Sieur de la Motte as its commander,

instructing him to have a vessel fitted out for the expedition to the Gulf

of Maine. About fifty Frenchmen, including two Jesuit brothers,

Gilbert du Thet and Quentin, boarded the ship, which left France in

January 1613. Landing at Port Royal, they were joined by Biard and

Massé. Using Champlain's maps, and probably guided by Biard, who

was familiar with the area as far south as the Kennebec, the vessel

sailed toward Penobscot Bay. Arriving on the eastside of Mount

Desert Island, the vessel anchored in a harbor.

At Mount Desert Island, "a great crowd of savages" came to see

the French, bringing a sick child to Biard. Healed by the Jesuit, the

child was baptized and given the name of its new godfather, Nicholas

de la Motte. Hearing that the French "had some intention of making a

settlement there," Bessabez of Penobscot "came to persuade us, with a

thousand promises, to go to his place" at Kadesquit (now Bangor).

Instead, invited by local tribespeople to remain at Mount Desert

Island, the French began to build their settlement named Saint

Sauveur-"Holy Savior." Operating from their new headquarters at

Saint Sauveur, the Jesuits planned to embark upon their missionary

activities.

The Wabanaki tradition as told by the Penobscot chieftain

Joseph Nicolar relates these events as follows:

At about this period another white man came in his big

canoe and landed on the shore of the eastern coast almost in

the midst of the northern country, on a high island very near

the spot where [Gluskap] and the dog killed the first moose.

Here the white man planted his cross.

34

The Tears That Rush Upon My Brow

Disputing French political claims to Wabanaki territories, the

English colonists at Jamestown argued that the Gulf of Maine

belonged to Virginia. Realizing that their rivals had founded a new

settlement at Mount Desert Island, the English feared competition.

That same summer, Captain Argall of Jamestown received orders to

attack the Mission of Saint Sauveur, and surprised the infant colony.

Thirty-five Frenchmen were captured, and the Jesuit du Thet was

killed. Father Massé and thirty others were allowed to take two

shallops and leave the island. After a difficult journey, they were

rescued by fishing vessels, which took the hapless colonists back to

France. The Jesuits Biard and Quentin, as well as two other

Frenchmen, were taken to an English vessel off Pemaquid, which

carried them back to Europe. Meanwhile, Captain Argall received

instructions "to plunder and demolish all the fortifications and

settlements of the French

along the entire coast as far as Cape

Breton." Having razed Saint Sauveur, the English captured an Indian

at Passamaquoddy Bay. He showed them the way to Port Royal,

which they burned to the ground.

Meanwhile, still supplied by their French allies, Micmac

(Souriquois) warriors tried to maintain their dominant trading

position northeast of the Penobscot. From their Gulf of Maine

stronghold at Mount Desert Island, by then also known as Sourico

Island, sailing in shallops and armed with muskets, they could stage

lightning raids against their enemies, in particular the Bashaba of

Penobscot. In 1615, according to an English document, they

"surprised the Bashaba, and slew him and all his people near about

him, carrying away his women and such other matters as they thought

of value." A year later, this intertribal war on Maine's coast was

followed by "a great and general plague, which SO violently reigned for

three years together, that in a manner the greater part of that land was

left desert, without any to disturb or oppose our free and peaceable

possession thereof."

Because they were unfamiliar with the alien diseases introduced

by the newcomers from across the Atlantic, most Wabanaki victim

to highly contagious diseases such as smallpox and bubonic plague.

An estimated seventy-five percent of the native population, and

perhaps even more, perished during this epidemic. When it was over,

an Englishman wrote "that they died on heapes as they lay in their

houses and the living that were able to shift for themselves would

runne away, & let them dy

And the bones, and skulls

made such

35

a spectacle that as I travailed in that Forrest

it seemed to mee a new

Golgotha."

In the nineteenth century, still remembering this accursed period

in their people's history, old Penobscot Indian traditionalists

recounted the words spoken by the old man when he reported seeing

the "strange tracks" on the beach. Back in his village, he told the tribal

council of elders:

Upon seeing the strange tracks, all the warnings which have

been giving us, how that a time is coming when we must look

for the coming of the white man from the direction of the

rising sun

I could not withhold the tears that rushed

upon my brow. Knowing that a great change must follow his

coming it made me weak and the weakness overcame me,

because his coming will put a bar to our happiness, and our

destiny will be at the mercy of the events. Being satisfied that

me and the young men have seen the tracks of this strange

man, it becomes as our gravest duty to prepare ourselves

and people SO to be ready to meet the changes which may

follow.

36

Bibliography

Anon., The Description of the Countrey of Mawooshen, in: S.

Purchas, Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes

Contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande

Travells by Englishmen and others, Vol. XIX, Glasgow, James

MacLehose and Sons, University Press, 1907.

Archer, G., The Relation of Captain Gosnold's Voyage to the North

Part of Virginia (1602), in Massachusetts Historical Society

Collections Third Series, Vol. 8 (1843) pp. 72-81.

Asher, G.M., Henry Hudson the Navigator, London, 1860.

Bakker, P., Trade Languages in the Strait of Belle Isle, Paper read at

Labrador Conference on cross-cultural contact in Strait of Belle

Isle, Oct. 1988 [n.p.].

Biard, P., in Thwaites, ed., The Jesuit Relations, Vols. 1,2,3,4.

Biggar, H.P., The Voyages of Jacques Cartier, Public Archives of

Canada, Ottawa, 1924.

Brereton, J., A Brief and True Relation of the Discovery of the North

Virginia, etc., made this present year 1602, by Captain B.

Gosnold, Capt. B. Gilbert, etc., by the Permission of the Hon.

Knight Sir W. Raleigh, London 1602, in Mass. Hist. Soc.

Collections, 3rd Series, Vol. 8, pp. 83-123.

Burrage, H.S., Gorges and the Grant of the Province of Maine 1622, a

Tercentenary Memorial, Augusta, 1923.

Burrage, H.S., ed., Rosier's Relation of Weymouth's Voyage to the

Coast of Maine, 1605, with an introduction and notes, Portland,

1887.

Champlain, S. de, Works, (edited by H.P. Biggar), 6 vols., The

Champlain Society, Toronto, 1922-1936.

Charlevoix, P.F.X. de, History and General Description of New

France, New York: F.P. Harper, 1900 (translated with

annotations by J.G. Shea), 6 vols.

DeCosta, B.F., Gosnold and Pring 1602-1603, in New England

Historical and Geneological Register, Vol. 32 (1878):76-80.

Eckstorm, Fannie H., Indian Place Names of the Penobscot Valley

and the Maine Coast (1941), University of Maine at Orono Press,

1978.

Gorges, Ferdinando, A Briefe Narration of the Originall Undertakings

of the Advancement of Plantations into the Parts of America,

Especially, shewing the Beginning, Progress and Continuance of

that of New-England (1658), in: Collections of the Massachusetts

Historical Society, 3rd Series, Vol. 5: 45-93.

Hakluyt, R., The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of

the English Nation, (1589-1601).

Hakluyt's Voyages, Selected and edited by R. David, Boston:

Houghton Miflin Company, 1981.

Hamilton, M.W., Henry Hudson and the Dutch in New York, Albany,

1964.

Hoffman, B.G., Cabot to Cartier, Sources for a Historical

Ethnography of Northeastern North America 1497-1550,

Toronto, 1961.

Kennedy, J.H., Jesuit and Savage in New France, New Haven, 1950.

Leger, M.C., The Catholic Indian Missions of Maine, 1611-1820,

Studies in American Church History, Vol. 8, Washington, DC,

1929.

Lescarbot, M., The History of New France, (edited by H.P. Biggar),

3 vols., Publications of the Champlain Society, Toronto, 1911-

1914.

Mitchell, D., The Jesuits, a History, New York, 1981.

Morison, S.E., The European Discovery of America, Vol. 1, Northern

Voyages, New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Morison, S.E., The European Discovery of America, Vol. 2, The

Southern Voyages, New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Murdoch, B., A History of Nova Scotia, Halifax, 1865, (3 vols.).

Nicolar, Joseph, The Life and Traditions of the Red Man, Bangor:

C.H. Glass, 1893, (reprinted, with a new introduction by J.D.

Wherry, by Saint Annes Point Press, Fredericton, 1979.

Reid, John G., Acadia, Maine, and New Scotland, marginal colonies

in the seventeenth century, Toronto, 1981.

Sauer, C.O., Sixteenth Century Norh America, The Land and People

as seen by the Europeans, Berkeley, 1972.

Sauer, C.O., Seventeenth Century North America, Berkeley, 1980.

Smith, John, A Description of New England, London 1616, in:

American Colonial Tracts Monthly, Vol. II, No. 1 (May 1898),

Vol. 2: 1-39.

Smith, John, New England's Trials, London 1622, in Ibid., Vol. II, No.

2 (June 1898): 1-23.

Thayer, H.O., The Sagadahock Colony, Portland, 1892.

Thwaites, R.G., ed., The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents,

Travels, explorations and missions of the Jesuit missionaries in

New France, 1610-1791 (73 vols.), Cleveland, 1896-1901.

Wright, L.B., ed., The Elizabethan's America: A Collection of Early

Reports by Englishmen on the New World, Cambridge, 1965.