From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Search

results in pages

Metadata

Haney, David H

Haney, David H.

bit Bar) Trustein 14/3/24

tapt.!

5/2/15 focus on nood developmt.

First If repleased for

Promotion of CANP?

Note: See also C. Eliot

file for his "Bringing

the americanized

Puckler back to

The legacy of the Picturesque at Mount Desert Island:

germany (2007)

controversies over the development of Acadia National Park

DAVID H. HANEY

Mount Desert Island, off the northern coast of Maine, is one of the most

time, the local communities of farmers and fisherman had been in existence

significant landscapes in the history of the pursuit of nature in America in the

long enough for much of the original timber to have been felled and the wild

late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Though similar to other nature

life hunted out. While valued for the aesthetic 'wildness' of its land forms, the

resorts in the Northeast of the same period, Mount Desert Island was particu-

Island was never understood as a true wilderness, that is as a place where

larly notable for the rapid rate at which it was transformed from a relatively

human influence was minimized. Instead, when the first sojourners began to

isolated, even primitive, place in the mid-nineteenth century to one of the

arrive in the 18 50s and 1860s, they most frequently turned to the language of

most élite summer resorts by the century's end. The Island was further distingu-

the Picturesque to describe their perception of the precious wildness of the

A08,

ished when, in 1916, it became dedicated in part as the National Park now

Island landscape.

known as 'Acadia'; out of all comparable resorts east of the Mississippi River,

The topography of the place was, in fact, well suited to the Picturesque

1915,

it was the first to be so recognized. The popularity of the Island as a destination

genre. The highest mountain peak on the Island reaches a mere 1500 feet,

was due largely to factors common to the entire Maine coast; the cool, clean

relatively tame even by Eastern standards. Softened by glacial scouring, the

1922.

coastal air was made increasingly accessible by improvements in transportation,

mountain peaks appear as soft, rose-hued granite masses rising above the low

providing relief from the sweltering summer heat of the nearby urban areas.

coastal tree-line, providing visually pleasing textures without being overtly

Yet the characteristic that attracted the most attention, and which was most

intimidating. The first entry in the monumental two-volume Picturesque

in keeping with the National Park concept, was quite simply the Island's

America, published in 1872, was actually a pictorial essay on Mount Desert

unique topography: along the entire Atlantic seaboard of the United States,

Island accompanied by a text using it as the example to explain the proper

the only mountains to reach the sea are to be found there.

means of obtaining the Picturesque experience. Like the Picturesque itself,

The history of the Island as a destination for city dwellers began with the

however, the landscape was subject to the nuanced definitions of the term,

arrival of landscape artists such as Thomas Cole and Frederick Church in the

which at Mount Desert in mid-century resulted in contradicting visions of

1840s, who came specifically to paint 'sublime' scenes of crashing waves and

how the Island should be developed as a resort. Some writers believed that

rocky shoreline. Though attracted to the power and roughness of the Island's

the rough, wild landscape character they valued should be literally reflected

landscape, these artists also depicted the quieter, more pastoral, lake valleys of

in primitive resort conditions, free from the constraints of fashion and high

its interior, and often included some evidence of the human presence. At that

society found at so many other places, such as Newport, Rhode Island. Others

0144-5170/96 1996 TAYLOR

FRANCIS

275

J. of Carden History 16 (1996) 275-97

JOURNAL OF GARDEN HISTORY HANEY

thought that the character of the landscape called for the application of

in 1915, and later, in 1917, from the National Park Service. The series of

Picturesque gardening principles, and for the general refinement of the summer

debates over landscape development that began once his plans were made

communities to reflect a similar aesthetic.

public in 1920 was perhaps the most intense that the Island has ever seen. My

The latter view generally prevailed, with the result that elaborately designed

essay examines the events of this controversy, focusing on the differing concep-

estates, known diminutively as 'cottages,' began to predominate in the Island

tions of the ideal experience of 'wild nature.'

landscape by the end of the century. The result of all of this landscape improve-

The arguments expressed in the 1920s and 1930s are remarkably similar to

ment was the increasing privatization of former open lands, restricting public

the dissenting opinions of nineteenth-century travel writers. These later

access to the point of threatening the very reason for the existence of the

debates may perhaps be traced back to the ambiguities of a conception of

resort - the pursuit of nature. Realizing this, Charles W. Eliot, President of

wildness derived from the Picturesque. In the early twentieth century at Mount

Harvard University, led the effort to establish a public Trust in 1902, for the

Desert, as elsewhere, the problem of landscape definition was intensified by

purpose of holding lands free from development in perpetuity while main-

the increased pressures of technological and social change, symbolized in the

taining public access. He was inspired by the writings of his recently deceased

person of the automobile tourist, who at the close of the twentieth century

son, Charles, a landscape architect, who had conceived of a similar Trust in

remains a problematic and powerful presence in the cultural landscape.

Massachusetts, which was also the model adopted for the English National

Trust. The younger Eliot had cautioned against the unrestricted construction

of private estates on the Maine shore, seeing them as a threat to the 'flavor of

Rockefeller's pursuit of perfection

wildness.' At Mount Desert, it was President Eliot, with the assistance of his

In Rockefeller's vision of the Park as a perfected landscape, there was no place

friend (George B. Dorr, who went on successfully to persuade the Federal

for the unplanned, disorderly, or crude. All elements were to be carefully

Government to accept Trust lands as the nucleus of what was later to become

coordinated to facilitate what he considered to be the ideal means of experien-

Acadia National Park.

cing nature: as a series of landscape scenes viewed from a moving carriage.

Though President Eliot was himself an avid camper and believer in the

The carriage roads he planned and funded were more carefully engineered

importance of outdoor life, his understanding of park-making was akin to

than most rural highways, and the self-consciously rustic bridges and other

dedicating the landscape as cultural monument, extending the ideals of the

stonework features that were built were deceptively expensive. Known to be

City Beautiful movement to a regional scale. This conception of park implied

an inherently methodical and persistent man, Rockefeller maintained control

the 'improvement' of the landscape through the construction of roads and

over every detail of design and construction, even down to the purchase of

other infrastructure, which would of course require massive funds not readily

gravel. His penchant for order extended well beyond purely aesthetic and

available to the Trust or to the post-First World War Government. As President

economic decisions, however. Until well into the mid-1930s, when the car-

of Harvard, Eliot was well experienced at fundraising. Having made the

riage road system was nearly complete, he continued to hold title to the only

acquaintance of John D. Rockefeller, Jr, while negotiating donations to the

properties over which the few access roads had been constructed. He believed

Harvard Medical School in 1903, he invited Rockefeller to join the summer

it was his right to decide who could enter the system and by what conveyance,

community at Mount Desert. Rockefeller declined this initial offer, but later

despite the fact that the roads were built on publicly owned land It seems

accepted, and in 1910 began construction of his own estate, which was to

that a perfected vision demanded that even the observers themselves had to

include an elaborate system of carriage roads patterned on those laid out on

fit in to the aesthetic scheme.

his father's estate, recently completed under his own supervision. Not content

Though public improvement projects such as trail-building had traditionally

to limit his construction activities to his own property, and quite possibly

been undertaken as group activities under the direction of the Village Improve-

influenced by President Eliot's writings, Rockefeller requested permission to

ment Societies, Rockefeller declined on several occasions to join organizations

extend his carriage roads into public lands, receiving approval from the Trust

that would have compromised his autonomy.3 3 This state of affairs did

not

go

276

MOUNT DESERT ISLAND

annoticed among a summer colony composed of individuals who were used

synibols of civilization, roads should be excluded from most park lands. This

to wielding their own political power at home. From (920 to i 1933,

anti-development attitude worked against the vasi majority of the public, who

Rockefeller's plans were the subject of much public debate in a series of events

could only afford to visit by automobile. A kind of compronese evolved: parks

collectively referred to 38 The road controversies Quite simply, the Island

were divided or 'zoned' into wilderness areas. where development would be

community was divided into those opposed to Rocketeller's road construction

numinazed, and scenic areas, where facilities, such is reads with lookouts,

plans, and those in support. There was 80 clear pattern on determine who was

would be provided for the comfort and enjoyment of the auto tourist. Yer

for and who against: there were members of the different Village Improvement

despite the mediating effect of the great scale of many of the Western parks.

Societies on both sides, and neither was any hard-line division between Island

communities easily discentible

The whole series of debates can be summarized as a struggle for power

among the sustement elites; it would be wrong to suggest. however, that either

party WBS insincere 112 fighting for its respective concepts of the natural land-

scape Both Rockefeller and his critics presented their vision of the ideal park

experience quite clearly, be in favor of a refined perfected view of nature.

and the opposition inclined towards : wilderness that required minimal

human intervention. At the heart of the argument lay the problem of deter-

mining the inherent character of the Island landscape; the situation recalled

the earlier nineteenti-century division between those who saw the Island

landscape RS wild and rough, and those who SRW it as the background to the

refined resort. Rockefeller's road-building plans were not limited to the area

adjacent to his estate. but were intended to transform all the Park east of

Somes Sound (the firrd-like body of water that infurcates the Island). Once

the extent of his plans were realized it became apparent to all that the former

"roughness" of the Island would be substantially mediated by the refinement

of the elaborate carriage roads

Mount Desert was nor the only place where such issues were at stake read-

building in public parks was a major topic of discussion during the early years

of the twentieth century Though debate over seried carriage-road construc

tion in `natural parks was discussed by the landscape architect Charles Eliot"

as early as the r8gcs. the advent of the automobile introduced an even greater

urgency to the problem of accessibility. The National Park Service was formed

in 1916 partly as R response to the need to provide roads and facilities for the

ever-increasing numbers of antomobile tourists. Not surposingly, plans for

National Park development evoked strong negative reactions from purists

FIGURE : B.P. de Cesta. :Among the Mountains, 1305 patient

around the country who believed that 3 'wilderness quality should be pre-

entrasiasts relax amida a typical Mount fannstead, with the silhourtic of (ii) undentified Adome

served by minimizing any form of development, Critics of development gener-

Dosen pork rising in the background (photo: countesy of the University of Texas, Harry Ransom

ally believed that construction threatened ecological purity. and that as

Humanities Research Center. Antin. TX)

277

JOURNAL OF GARDEN HISTORY : HANEY

opposition remained, and some projects were actually abandoned." The specific

issues have changed, yer the general debate over how and whether park lands

should be developed continues to be an unresolved philosophical and political

problem in the late twentieth century.

The problem of development at Mount Desert Island in the 1930s and 1930s

was perhaps even more intenses than elsewhere. The success of dividing wilder.

ness from developed areas depended on a complete spatial separation, which

would be much more difficult in this small park, especially given the extent

of Rockefeller's plans. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the debates at

Mount Desert lies in the fact that the arguments for and against wilderness

and development were not really derived from 28 objective evaluation of

existing conditions. The Island was already a settled, rural landscape when the

first sojourners arrived in the 1840s (figure 1). While the relatively un-

NOT

developed. mostly mountainous, areas that formed the heart of the park ND

the early twentieth century were at that time heavily wooded, these had

us

generally been logged and burned over in the past, and were riddled with old

roads for the hauling of timber Most of the wild animals had been extirpated

long ago; in the classic definition of the concept, the Island simply was not a

true wilderness. Yet the arguments for 'accessibility were also problematic.

By the time that Rockefeller began his road projects in the 1910s, the island

was dominated by a highly developed system of resorts, interconnected by

trails and roads. Few areas were not within easy walking distance of the summer

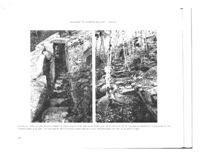

cottages (figure 2). In fact, scenic carriage roads had been in use on the Island

since the 1890s, one by the Sound, the other along the Eastern shore over-

looking the Atlantic Ocean (figure 3).

FIGGRE 2. A cottager poses on one of the many chaborate stone-paved mails that with common

OIL the Island by the late sineteenth century. By this time liking was is popular and fashionable

activity for both men and women (Northeast Harbor Maine Archives: published in Trails of

History by TOM Sr GERMAINE and JAY SAUNDERS [Bar Harbor, ME. 1992]) (photo: courtesy

of authors - the original is now presumed lost).

Hard on the arrival of these conveniences came the era of laxurious living with EVEN

the trails 30 smoothed down that is lady may walk from Asticose to Jerdan Pond in kid

slippers and high heels' (Francis G Peabody, Bar Harbor Times, jo January 1931)

if am sure the Secretary will understand that much is this territory 25 really inaccessible

except in the mountain dimber, and this system of road mails will farnish opportunity

for others besides the mountain climbers to see this beautiful country' (Congressman Nelson

of Maine, 1934).

278

MOUNT DESERT ISLAND

neither party took the issue of defining nature lightly, though in the final

analysis the whole debate could be reduced to aesthetic issues. The emphasis

here was not on the ecological purity of 'primeval conditions, but on the

importance of natural landscape to human experience.

The discussions were only partly about abstract notions of nature and cul-

ture: much attention was given to the way the experience was set up spatially

in the landscape. Arguments often centered on basic design issues: which was

of the ideal width - road or trail; should vegetation be retained to create a

sense of separation and enclosure, or should it be removed to reveal expansive

views; would existing simple rustic roads or elaborate constructions be more

appropriate expressions for the pursuit of nature (figures 4 and

Viewer Controls

Toggle Page Navigator

P

Toggle Hotspots

H

Toggle Readerview

V

Toggle Search Bar

S

Toggle Viewer Info

I

Toggle Metadata

M

Zoom-In

+

Zoom-Out

-

Re-Center Document

Previous Page

←

Next Page

→

Haney, David H

Details

Series 2