From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Search

results in pages

Metadata

Emmet, Alan

Emmet Alan

ALAN EMMET has written on landscapes

and gardens for numerous periodicals. She is a

member of the Advisory Committee of the Gar-

den Conservancy, and a trustee of the Society for

the Preservation of New England Antiquities,

for whom she served as a garden history consul-

tant. She recently coauthored a historic land-

scape report for the National Trust for Historic

Preservation on Chesterwood Daniel Chester

Ac

French's summer home and studio.

Shank

The draped summerhouse beside

parterre garden Photo by Peter Mar

Reproduced by permission.

University Press of New England

publishes books under its own imprint and is the publisher for

Brandeis University Press, Dartmouth College, Middlebury College Press,

University of New Hampshire, University of Rhode Island,

Tufts University, University of Vermont, Wesleyan University Press,

and Salzburg Seminar.

University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 03755

© 1996 by University Press of New England

All rights reserved

Printed in Singapore

5 432 I

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Emmet, Alan.

So fine a prospect: historic New England gardens / Alan Emmet.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN o-87451-749-4 (alk. paper)

I. Historic gardens-New England. 2. Gardens-New England-

History. I. Title.

SB466.U65N4825 1996

712'6'0'9944-dc20

95-36320

Title page spread: Grandmother's Garden, Lydia Field Emmet, oil on canvas, ca. 1912.

(National Academy of Design, New York, New York)

HE RASPBERRIES were dusted with

T

frost this morning, SO silvered with it that I

could hardly tell which ones were ripe, but the

sweet, perfect, dark red berries dropped into my hand

as easily as ever. The sun shone through the canes, and

the leaves and berries were translucent. The rough,

whitened grass beneath the sugar maple was dappled

with sparkling yellow leaves. As I picked, I thought of

those other gardeners, the ones whose private letters

Introduction

and diaries I have been nosing SO earnestly through. We

must have something in common, they and I. Surely, all

of them must have had those moments of pure delight

So Fine a Prospect

in their gardens, when some homely detail or grand ef-

fect makes it all worthwhile.

Every year, every season, every day, and even every

hour gardens change. Subject to natural rhythms of

growth and decay, responding to care or neglect, gar-

dens of every sort are continually evolving. Depending

on the quality of light or the angle of the sun, the same

place looks altogether different at different times and in

different seasons. If constant change is the very essence

of a garden, then there is no finished product and no

point at which the need for upkeep ceases. There is no

moment of which we can say, "This is it" or-looking

back- "That was it." Certainly there are periods in the

life of any garden when maintenance reaches its apo-

gee, when the initial plantings approach maturity, and

when painters or photographers are most likely to at-

tempt to capture a moment of perfection. But the inevi-

tably transient quality of a garden-the very fact of its

evanescence--is reason enough to investigate its origins.

For me the most intriguing questions about a garden

are who built it and why.

Before the first spade cleaves the earth, before the

first stakes mark the course of a new path, before the

first tree is cut or the first tree planted, the garden

maker has decided to alter the landscape. The chief rea-

son for the change is to make a place more beautiful,

more productive, or in the usage of the eighteenth cen-

tury, to "improve" it. Inspired by pictures in the mind,

the gardener seeks to make a fantasy become real.

Garden makers have always had visions all their own.

One may have followed a modest dream of beauty,

while another imagined a grand reordering of the land-

scape. A third may have aimed at rivaling the accom-

plishments of others. Some gardeners have deliberately

adapted the dictates of contemporary fashion to their

own terrain. Others have been influenced by current

styles but less consciously, as if by osmosis. And then

xi

Thomas Hancock's stone house, built in 1737, and terraced

front garden on Beacon Hill, Boston, in a photograph taken

nurseries, Hancock and other American gardeners or-

by G.H. Drew. ca. 1860. The dome of the Massachusetts

dered all their plants from Europe. Hancock wrote to a

State House is visible at the right. The once magnificent gar-

London nurseryman to purchase dwarf trees, espaliers,

den was near its end; the house was demolished in 1863. (So-

and other plants. He boasted of his view in a letter to

ciety for the Preservation of New England Antiquities)

this nurseryman: "My Gardens all Lye on the South

Side of a hill with the most beautiful Assent to the top &

its allowed on all hands the Kingdom of England don't

pagoda. had a spire topped with a gilt grasshopper as il

afford SO Fine a Prospect as I have both of land & water.

weathervane.

Neither do I intend to Spare any Cost or pains on mak-

On another slope of Boston's Beacon Hill, overlook-

ing my Gardens Beautiful or Profitable."

ing the Common. Thomas Hancock built himself a fine

In nearby Medford in the 1730s, Colonel Isaac Roy-

stone house in 1736. He commissioned a local gardener

all, with a fortune from trade with Antigua, built the

[1) "undertake to lavout the upper garden allys. Trim the

handsome house that still stands. The central walk was

Beds S till up all the allies with such Stuff as Sd. Han-

on an axis with the doors of the mansion. The walk ex-

cock shall Order and Gravel the Walks & prepare and

tended five hundred feet behind the house, between

Sodd ve Terras.`` Before the establishment of local

tagonal garden beds summerhouse to a terraced and mount a carved crowned wooden with figure an OC- of

vic

INTRODUCTION

Mercury. 10 A few miles away, in Lincoln, the Codman

desire for "Prospect" meant that elevated sites were

house, a close contemporary of Colonel Royall's, still

preferred and that terracing was almost universal. The

overlooks a "Front Yard" noted in a 1778 inventory and

one landscape feature that more modest houses would

stepped terraces that may be as old as the house itself. 11

have had in common with the great mansions was an

Estates of the Cambridge Loyalists were noted for

enclosed and planted forecourt, scaled down to become

their gardens. which contained similar features. Henry

a simple dooryard garden with a path from the gate to

Vassall's garden, laid out in the 1740s, had the typical

the house.

enclosed front yard, or forecourt, and central axial path.

This cursory look at a few pre-Revolutionary gar-

His path was paved with beach stones. Beds edged with

dens neglects their horticulture-the flowers, fruits,

boxwood were planted with fruit trees imported from

and trees in which the owners took such pleasure and

France and England. 12 The forecourt of Richard Lech-

pride. Plants were the life of these gardens, but it is

mere's 1761 mansion was enclosed by a fence with

their design features that characterize them as belong-

carved pineapple finials and was planted with rows of

ing to a particular period. These gardens near Boston

linden trees that stood until the hurricane of 1938. A

were representative of their era; similar gardens were

broad path led to a raised terrace and the entrance por-

being made in and around other cities at the time.

tico. The center hall of this house opened onto the gar-

Eighteenth-century estate owners imported not only

den at the rear, where the path continued down some

plants and trees but also the books they depended on

steps, straight through the garden, to terminate at an

for guidance in the management of both the useful and

arbor.13 At John Vassall Jr.'s house (now the Vassall-

the ornamental aspects of their grounds. There were no

Craigie-Longfellow House, administered by the Na-

helpful American books at the time. Henry Vassall, for

tional Park Service), built in I759, the landscape was

example, owned and presumably consulted John Mor-

arranged in the same typical fashion. The house was

timer's The Whole Art of Husbandry (London, 1716) and

built on a terraced platform to provide a broad view of

Richard Bradley's A General Treatise of Husbandry and

the Charles River marshes. A brick-walled forecourt

Gardening (1725). The builder of the original Codman

was planted with rows of American elms. 14 These grand

house, Chambers Russell, turned to William Ellis's The

mid-eighteenth-century estates in and around Boston

Modern Husbandman (1742) and Edward Lisle's I757

were alike in their geometrical organization around a

treatise on the same subject. 15

central axis, of which the house itself was the focus. The

In their gardens, Americans of the colonial period

Terraced gardens at the

1760 East Apthorp house,

off Linden Street near Har-

vard Square in Cambridge,

Massachusetts; photograph

ca. 188o. (Society for the

Preservation of New Eng-

land Antiquities)

So Fine a Prospect

XV

whered to the styles of the lands of their origin. When,

5. Christopher Tunnard, A World with a View: An Inquiry

11685, Sir William Temple described an English gar-

into the Nature of Scenic Values (New Haven, Conn.: Yale Uni-

den. Moor Park in Herefordshire, as "the perfectest fig-

versity Press, 1978), 67.

111c of il garden I ever saw," he could have been writing

6. F. R. Cowell, The Garden as a Fine Art: From Antiquity to

about an eighteenth-century American garden. 16 Moor

Modern Times (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1978), 8.

Park may have been more ornate than most New Eng-

7. Abram English Brown, Faneuil Hall and Fanueil Hall

lind gardens, but its major design features were the

Market (Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1900), 28.

silline it close relationship between the architecture of

8. Alice G. B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State

the house and the plan of the garden, the bilateral sym-

(New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1931), I:32. Hancock

metry of the garden along the spine of a central path,

uses the word "allys," or "allies," to mean beds of planting.

the use of terracing, and the inclusion of arbors and

9. Ibid.

summerhouses. As we will see, New Englanders contin-

IO. Ibid., I:39.

used to make and maintain this type of garden long after

II. Middlesex County Probate Records (East Cambridge,

1/10 establishment of the new nation.

Mass.), docket no. 19593.

I2. Rupert Ballou Lillie, "The Gardens and Homes of the

Loyalists," Cambridge Historical Society Proceedings for the

Vores

Year 1940 (Cambridge, Mass., 1940), 26:54.

I3. Ibid., 57.

I4. Ibid., 52-53.

I5. Vassall's inventory is described in Lillie, "Gardens and

1. Greg McPherson, "Shedding the Illusion of Abun-

Homes," 53. Russell's books are listed in a 1767 inventory of

dance," landscape Architecture 79 (April 1989): 128.

his estate, Middlesex County Probate Records, docket no.

is 1.00 Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the

19591.

Harmoned Idea in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

16. Sir William Temple, quoted in Ann Leighton, Ameri-

luny). 84-85.

can Gardens in the Eighteenth Century (Boston: Houghton Mif-

is lbid., 104-5.

flin, 1976), 328.

*

Ann Leighton, Early American Gardens (Boston: Hough-

fill Mittlin, 1970), 6.

INTRODUCTION

there are the innovators, whose gardens have been in-

not strictly a revival of anything-represents more than

spired by fresh insights and new possibilities. These gar-

anything else nostalgia for an imagined past, as often as

deners may have followed literary sources, history dimly

not a New England past.

guessed at, or wisps of memory and dreams. Those who

introduced novelty in design may have ended up as set-

ters of the next trend or else were relegated to posterity

as solitary eccentrics in their unique and private garden

Leo Marx has pointed out two different meanings of

cul-de-sacs.

the word "garden," meanings that are in essence con-

Curiosity led me to investigate the conditions under

tradictory. Both interpretations have played significant

which some of New England's most important gardens

roles in American history. Marx quotes as one example

were created during the first century and a half of this

Robert Beverley's comment in his 1705 essay, History

nation's independent life. People express through their

and Present State of Virginia, that the reason there were

gardens the degree of their self-confidence as well as

SO few gardens in Virginia was that the entire region

their attitudes toward the land. Some have sought to

was a garden. In this sense. the term "garden" stands

dominate the place they called their own, whereas oth-

for the "Edenic land of primitive splendor," where Na-

ers have tried to enhance the inherent qualities of the

ture provides both bounty and beauty. This was the

landscape. The names that people have given to their

ideal that had drawn voyagers and settlers to America

places often reveal their intentions as well as the sources

and that, despite deprivation, climatic extremes, and

of their inspiration: Roseland, Bellmont, The Vale.

dread of the wilderness, continued for decades to in-

The gardeners of New England have always had

spire expeditions and expansion further westward. The

much in common with each other. They share tradi-

other meaning of the word "garden," according to

tions, patterns of settlement, and a rigorous climate.

Marx, is a piece of cultivated ground, from which those

Over the years many have been linked by their earnest

who work on it can produce beauty and abundance.

efforts to expand knowlege and better the human con-

While sounding more prosaic than the proverbial "land

dition through scientific experimentation in agriculture

of milk and honey," this definition describes the "mid-

or horticulture. Many, too, have shared a moral bent, a

dle landscape," neither wild nor densely urban, that

belief in the ennobling influence of beautiful surround-

represents the pastoral ideal SO prevalent in American

ings. In the first period of national life after the Revolu-

thought.

tion, New Englanders did not abandon the ways of the

This book is concerned with gardens made for pri-

Old World but were quick to adapt to the opportunities

vate use, beauty, and pleasure. These gardens are not

offered by the New. As a result, they contributed far

necessarily enclosed, but they are separated or set off in

more to the national culture than might be expected,

some way from the surrounding landscape. Their ap-

considering their numbers and the limited size of the

peal owes as much to what they exclude as to what they

area. Although the region's influence gradually de-

contain. The best gardens convey this sense of their

creased as the country grew, idealized images of New

separateness, a feeling of seclusion and sanctuary from

England are important national models to this day. In-

the workaday world. Ann Leighton put it almost bibli-

deed, the developer of a recent subdivision in the dry

cally: "A garden, to be a garden, must represent a differ-

prairie of central Texas named it "Nantucket," bringing

ent world, however small, from the real world, a source

in old dock pilings and maritime flotsam to create a

of comfort in turmoil, of excitement in dullness, secu-

"theme" landscape of the New England coast. A village

rity in wildness, companionship in loneliness."4

on a hill, white houses facing on a green, tall elms arch-

Every garden is unique, depending on the purpose

ing overhead, and a white church spire pointing heav-

for which it was designed, the lay of the land, and any

enward: for many Americans this picture represents sta-

number of other factors. Size is one variable that signif-

bility, tradition, national roots, and a retreat from urban

icantly affects the character of a garden. The smallest

stress. Revival styles based on New England examples

might be a flowery, fenced enclosure adjacent to a house.

have been popular for domestic architecture and gar-

At the other end of the scale would be a rural estate ex-

den design for nearly a century, within and beyond the

tending over hundreds or even thousands of acres. Tra-

region. The popularity of herb gardens for instance-

ditionally, large landed estates were intended to be agri-

xii

INTRODUCTION

culturally productive; with imagination and skill, the

the other hand, gardens that continue in private owner-

whole rural scene could become a garden, a harmo-

ship are just that: private.

nious unity where use and beauty flourished.

Christopher Tunnard once referred to a garden as "a

luxury of the imagination."5 F. R. Cowell observed

that

only in periods of high civilization has gardening been

Before the Revolutionary War, during the first century

elevated above a necessary and useful craft to become a

and a half of New England's European colonization.

fine art. Both writers pointed out that with the oppor-

gardens were seldom characterized as works of art. To

tunity for self-expression in the landscape there was

the first settlers, luxury and leisure were inconceivable:

room for eccentricity. Luxury, eccentricity, and suffi-

survival was at stake. Utility was the chief consideration

cient leisure: it should come as no surprise that most of

during the seventeenth century, when families had to

the creators of the gardens described in these chapters

produce their own food, clothing materials, and reme-

had either inherited money or achieved worldly success

dies against illness. People put their gardens near their

on their own.

houses and fenced them against the depredations of

The selection of the gardens to be discussed had a

wild and domestic animals. Beds of vegetables and use-

certain inevitability. The gardens I chose are not neces-

ful herbs were arranged for convenience, divided by

sarily superior to others of their periods, even were it

straight and narrow paths, after the late medieval Euro-

possible to make such value judgments. There are many

pean fashion familiar to the settlers. The sole conces-

other gardens worthy of study, some of which I wished I

sion to fancy might be a sweet rose, grown from a pre-

might include as well as others unknown to me. More

cious slip carried on the long sea voyage.

gardens remain to be uncovered or discovered. The

As life in the colonies became more settled and se-

treasure hunt has no end.

cure, people inclined toward expanding and adorning

The gardens included here provide a chronological

their homes. Before the end of the seventeenth century

sequence from the early years of the republic to the pe-

those who were comfortably settled and reasonably well

riod prior to World War I. I chose gardens that either

off felt free to make gardens purely for their own en-

typify a particular period or exemplify an innovation. A

joyment. Few detailed descriptions survive of pre-

third criterion was the existence of a written record.

Revolutionary gardens. Maps, deeds, and probate rec-

Whether or not a particular garden still survives in any

ords are the most likely sources of evidence. In many

form, it was the diaries, the correspondence, and the vi-

cases, trees, walls, terraces, pathways, and the layout of

sual records that made it possible to study each garden's

beds survived well into the nineteenth century. Archae-

history and to inquire into the motivation of its creator.

ology is a potential source for more information. Mem-

All of the garden owners in these chapters had their

ories kept the early gardens alive, too, although remi-

own reasons for doing what they did, beyond the in-

niscences were often colored by sentiment for one's lost

evitable influence of the social and cultural milieu in

youth.

which they lived. The history of the relationship be-

The gardens of the rich and prominent left a greater

tween garden owners and the professional designers

mark than did those of ordinary people. In Boston in

some of them hired interested me for what it revealed

1700, Andrew Faneuil, a successful businessman, built a

about both. In this relationship the owner became a

mansion house on the side of Beacon Hill, above

client, dependent on the expertise of the professional.

Tremont Street. Here he and, after him, his nephew

At the same time, the owner was also a patron, with the

and heir, Peter Faneuil, developed a seven-acre garden

opportunity to provide support and scope to the de-

famous for choice fruits, hothouses, and flowers im-

signer, as well as the ultimate power to terminate their

ported from France. Terraces marked the descent from

association.

the house to the street and also rose behind the house,

The gardens in these chapters are scattered across

supported by walls and steps of hewn granite. Railings

New England. Surviving records allowed me to dis-

along the edges of the terraces were surmounted by gilt

cover four gardens that are entirely lost. Although this

balls. At the top of the garden was a summerhouse with

is in no sense a guidebook, most of the extant gardens

a splendid view of Boston Harbor. This fanciful struc-

that I have written of can be visited by the public. On

ture, said to have been patterned after an oriental

So Fine a Prospect

xiii

E

DITH WHARTON, at thirty-eight, was tired

of Newport, the spot where she had spent every

summer ofher life. The year was 1900. You would

think she might have been satisfied. After all, she had

gotten her way in everything.

Edith Jones had married Teddy Wharton, an ami-

able bon vivant thirteen years her senior, in 1885, when

she was twenty-three. Together, they followed the pat-

tern of Edith's life as a child: New York City winters,

Chapter I5

Newport summers, and frequent trips to Europe. After

fifteen years they had no children but plenty of money,

especially after Edith's fortunes were unexpectedly en-

The Great Good Place

hanced by the legacy of a remote Jones cousin. They

lived in the style to which they were both accustomed.

The Whartons had bought a Newport cottage called

Edith Wharton at The Mount,

Land's End in 1893, a house well away from her

mother's. Edith promptly embarked on a radical re-

modeling of Land's End with help from Ogden Cod-

Lenox, Massachusetts

man, then in his early twenties and just embarking on

his ambitious career as a society architect. She and

Codman discovered their shared admiration for a re-

strained classicism in architecture and interior design.

They collaborated on a book that promulgated the clas-

sical style. The Decoration of Houses was barbed with

blasts at the frowzy, overstuffed rooms and houses in

which they and most people they knew had grown up

and still lived. First published in 1897, the book was an

immediate success. Two years later, Edith Wharton's

second book came out, The Greater Inclination, a collec-

tion of her previously published stories.

Even though she had now achieved recognition and

success as a writer, Edith Wharton wanted to change

her life, starting with Newport. The setting of Land's

End is bleak, as its name implies, and might on gray

days depress one who was not entirely enamored of the

sound of surf forever crashing against cliffs. Edith pined

to get away from the gloom and dampness, but she was

also determined to flee from the social constraints, the

"watering place trivialities" of Newport. 1 She yearned

for the deeper, richer life in the arts that her literary ac-

complishments seemed to offer. She longed to be with

creative people who shared her interests. She knew well

by then that her dull, benevolent husband did not.

During the summer of 1899, while Teddy and his

mother were in Europe, Edith stayed in her mother-in-

law's summer cottage in Lenox, in the Berkshire hills of

Massachusetts. The following year the Whartons rented

a house there and began looking for a property to buy.

Edith Wharton confided her enthusiasm to Ogden

206

August and September marked the height of the

Berkshire social "season." House-party guests filled the

giant cottages; others flocked to Curtis's Hotel in

Lenox or the Red Lion at Stockbridge. Hillsides were

claimed as the most desirable house sites, providing the

views that had originally attracted summer residents to

the region. In the 1880s, Joseph H. Choate, a New York

lawyer, began building the house and now famous gar-

den at Naumkeag on a hill in Stockbridge. During the

1890s the industrialist Stokeses, Sloanes, Schermer-

horns, and Westinghouses built mansions of unprece-

dented size over former hill farm pastures. The earliest

of these "cottages," in shingle style, were soon out-

classed by oversize Colonial Revival mansions that were

in turn superseded by palaces of brick and marble.

Shadowbrook (1893) had one hundred rooms; the

builder of Blantyre (1901) had his wife's ancestral Scot-

tish castle copied, antlers and all. The winner in terms

of ostentation may have been Bellefontaine (1899),

modeled on the Petit Trianon by architects Carrère &

Hastings, who also laid out the grounds. To Edith

Wharton, Bellefontaine's elaborately decorated archi-

tectural gardens were cold, impersonal, and the epit-

ome of vulgar ostentation. She told Ogden Codman

that he really ought to see the place an awful

warning!"

Edith Wharton early in her writing career. (The Beinecke

This was the Lenox that Edith Wharton had chosen

Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

for what she hoped would be a home for her spirit and

for a life of the mind. She was to thwart the conventions

of her upbringing many times in her life, but her choice

Codman: "I am in love with the place-climate, scenery,

of Lenox was entirely conservative. She was, after all,

life & all-& when I have built a villa & have planted

merely moving from the summer resort her mother had

my gardens & laid out paths through my bosco, I doubt

chosen to that of her mother-in-law. Her attitude to-

if I ever leave here." In the summer of 1901 the Whar-

ward "society" was always ambivalent. She scorned the

tons purchased the Sargent farm in Lenox, II3 acres

busy social "inanities" of both Newport and Lenox,

sloping down to Laurel Lake. Their reasons differed,

which did not endear her to her new neighbors. She

but both Edith and Teddy embarked eagerly on the

could not stand the pretentious flaunting of wealth. Ac-

project of making a country place for themselves in the

cording to Ogden Codman, Mrs. Wharton was rude to

Berkshires.

Mrs. Sloane, the queen of Lenox society. 6 On the other

For her escape to "real country," it is ironic that Edith

hand, Edith did not intend to be an outcast; in fact, her

Wharton chose Lenox, a community already known

efforts to belong and contribute to the Lenox summer

popularly as "the inland Newport." Although in an

community cut into her writing time and eventually ex-

earlier, simpler time, Lenox, like Stockbridge, had been

hausted her.7 She was very sociable--as long as she

a mecca for intellectual vacationers such as Nathaniel

could choose her companions. The Whartons' new

Hawthorne and the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, by

house was planned from the outset as the setting for

the 1890s both towns were enormously fashionable re-

continual hospitality.

sorts. The glamour once attached in the public eye to

The deed to the Lenox property was in Edith Whar-

writers and artists had faded when faced with the glitter

ton's name. It was she who selected the site for the

of the purely rich.

house, a knoll with a view southeast to Laurel Lake and

Edith Wharton at The Mount

207

the hills of Tyringham. The Whartons asked Ogden

remainder of his life. Two years after the fight with

Codman to design their house, Edith knowing that

Codman, he suffered his first "sort of nervous collapse"

Codman shared her penchant for rooms, facades, and

in the summer of 1903.

landscapes of cool restraint. She and he adhered with

Edith Wharton was undoubtedly a difficult and de-

religious zeal to the articles of faith that lay behind such

manding client in her own way. Even though she shared

designs. They chose as their model a seventeenth-

Codman's taste and wanted to keep him as a friend, she

century English manor house attributed to Christopher

told him she too thought it best that they not collabo-

Wren.

rate on the house after all. ¹ Codman, however, contin-

The Whartons liked his plans, Codman told his

ued to feel vindictive toward them both; he delighted in

mother in February 1901, "but I don't know what they

recounting their problems over the house and enumer-

mean to spend."9 That was the first hint of what soon

ating the defects he was sure he would have avoided.

grew into a full-blown quarrel over money. Codman

The Whartons turned to another architect, Francis

vented his anger at the Whartons in letters to his

Hoppin, whom they had known in Newport, to design

mother, letters that reveal him as childish and arrogant.

the house they christened The Mount. According to

He complained peevishly that "[t]he Whartons' house

Codman--a biased reporter, to be sure-Hoppin's life

instead of being my first is my sixth & the smallest of

was made miserable by fussy Mrs. Wharton, who

the four now building."10 Codman, at last successful

telegraphed him almost daily and made him revise the

and busy, felt that the Whartons still treated him as

plans continually. By the spring of 1902, Codman's feud

their pet protégée and resented his new prosperity.

When Teddy Wharton tried to beat down his commis-

sion, Codman waved the American Institute of Archi-

tects rule book at him; when Wharton shouted and

Postcard view from the flower garden to the Wharton house,

slammed a door, Codman walked away from the job,

Lenox, Massachusetts. An awning shaded the long terrace.

expressing relief and telling his intimates that Wharton

Edith Wharton penned the verse for Charles Eliot Norton in

was an idiot. Teddy Wharton was probably showing

1906. (bMS AM1193[336]; by permission of the Houghton

signs of the instability and paranoia that blighted the

Library, Harvard University)

J. Lenve

Cup. 7th,

208

THE GREAT GOOD PLACE

with the Whartons was superficially over, and he was

the lake. Edith Wharton developed her gardens within

invited back to decorate the interior of their house. He

this regional context.

told his mother gleefully that the Whartons rued the

day they had quarreled with him and were hoping now

that he could redeem Hoppin's failure. Edith Whar-

ton was pleased with Codman's designs for her rooms.

At the time she was involved in the building of The

Both Whartons were "very humble," gloated Codman;

Mount, Edith Wharton was immersed in Italian his-

"[h]owever I will try to be kinder now. "13 The patched-

tory and culture. Her first novel, The Valley of Decision

up friendship nevertheless became permanently un-

(1902), was set in Renaissance Italy. Impressed by this

glued three years later, when Teddy, refusing once again

book, her Berkshire neighbor Richard Watson Gilder,

to pay Codman's bills, called in a lawyer. 14 By that time,

editor of Century magazine, commissioned Edith Whar-

however, Codman had married a rich wife and no

ton to write a series of articles on Italian villa gardens.

longer really cared.

Edith and her eccentric English friend, Vernon Lee,

The Whartons' house was named The Mount, "not

with Teddy in tow, traveled from villa to villa in 1903.

because it was one," as Edith Wharton's friend Daniel

With the addition of painted illustrations by Maxfield

Berkeley Updike put it, "but because some old family

Parrish, the articles were published as a book, Italian

place had been SO named." The house was entered in

Villas and Their Gardens. The book was a popular suc-

the European style from a walled, statue-lined fore-

cess, more ambitious than Charles Adams Platt's pio-

court, which Codman considered "an utter failure," SO

neering book on the same subject, published a decade

small that "it looks like a clothes yard and is all out of

earlier. Edith Wharton wrote her book with the hope of

proportion." "16 This enclosed introductory space an-

encouraging in her American readers a return to form

nounced that privacy was valued here. Indeed, one pro-

and structure in the planning of their gardens. Her

gressed only gradually and in stages to the main rooms

opening sentence was guaranteed to shock: "The Ital-

of the house. "Privacy would seem to be one of the first

ian garden does not exist for its flowers; its flowers exist

requisites of civilized life," the authors of The Decoration

for What really counted, the chief lesson to be

of Houses had declared. ¹

learned from the great Italian country houses, was the

Each of the principal rooms at The Mount opened

intimate relation between the house and its garden.

onto a broad brick-floored terrace that ran the length of

Mindful of some new American estate gardens, she

the house on the rear, or garden, side. Shaded by a fes-

cautioned, "a marble sarcophagus and a dozen twisted

tive striped awning, the terrace overlooked the garden.

columns will not make an Italian garden." Instead of

Beyond the garden, D. B. Updike recounted, "a lawn

struggling to make a literal copy, one should strive for

sloped to a meadow stretching to the border of a little

"a garden as well adapted to its surroundings as were

wooded lake. One day when a party for lunch had gath-

the models which inspired it."

ered on the terrace, Mr. Choate [of Naumkeag] arrived,

Edith Wharton had plunged right into a contro-

accompanied by the Austrian Ambassador. 'Ah, Mrs.

versy that had torn the garden world in two when she

Wharton,' he said as he stepped from the house, 'When

plunked herself down on the side of formality and

I look about me I don't know if I am in England or in

structure. She could not abide the "laboured natural-

Italy."18 Mrs. Wharton may not have been entirely

ism" of the English landscape style and its later off-

pleased by this remark, presumably intended as a com-

spring. She had no use, either, for the flashy formless

pliment. The ambassador had missed the point, for The

gardens favored by some of the very rich. Mr. Mindon,

Mount was intended to be distinctly American, Mrs.

the harried protagonist of her 1900 story, "The Line of

Wharton's attempt to synthesize and adapt the histori-

Least Resistance," looks out at the grounds of his

cal principles of harmony and proportion to the New

Newport villa: "The lawn looked as expensive as a vel-

England scene. Rugged outcrops of limestone, native

vet carpet woven in one piece; the flower borders con-

white pines, and a giant American elm were featured in

tained only exotics.

A marble nymph smiled at him

her landscape. The house was painted white, with green

from the terrace; but he knew how much nymphs

shutters, that quintessentially American combination.

cost."20 Wharton's own garden at The Mount, indeed

The Whartons' barns and livestock enhanced the typi-

her entire place, could be characterized by the phrase

cal rural New England character of their view toward

she used to describe a Roman villa she admired: "the

Edith Wharton at The Mount

209

day-dream of an artist who has saturated his mind with

ing to work in the kitchen garden. In the afternoons she

the past.

took long rides on her horse, returning "stupid with

Having sited the house on a hillside, Mrs. Wharton

fresh air." She wrote her friend Sara Norton that "Lenox

was forced to deal with the slope. "We are going to ruin

has had its usual tonic effect on me, & I feel like a new

ourselves in terraces," she told Ogden Codman, "but

edition.

It is great fun out at the place now too-

the effect will be jolly."22 Before construction of the

Everything is pushing up new shoots-not only cab-

house could begin, however, there must be an entrance

bages & strawberries, but electric lights & plumbing."23

drive. For assistance with this project she called upon

Ogden Codman came to visit. In a typically snide

her niece, Beatrix Jones (later Farrand). "Trix," ten years

comment he told his mother, "The place looks forlorn

younger than Edith, was already well trained and estab-

beyond my powers of description and it will take years

lished as a "landscape gardener," to use her term for her

and a small fortune in Landscape gardening to make it

professional role. From the white-picket entrance gate

look even decent."2 But to Edith Wharton, when they

and the lodge, the drive runs for half a mile through a

moved into The Mount in September 1902, "[t]he views

double avenue of sugar maples, past the stable, then

are exquisite, & it is all SO still & sylvan-I have never

dipping and turning through a dense wood and emerg-

seen the Michaelmas daisies as beautiful as this year-

ing into a clearing, from which the house comes sud-

the lanes are purple. "25

denly into view.

After months in Italy, the Whartons returned to The

The next project, also designed by Beatrix Jones, was

Mount in June 1903 with happy anticipation. Edith

a kitchen garden, surviving now only in plans and a

Wharton was devastated by what she found:

photograph or two. No mere vegetable plot, this was an

elegant parterre 250 feet long, divided by paths into

eight squares and enclosed by a clipped hedge with top-

iary archways. At one end was a grape arbor; along the

Beatrix Jones (later Farrand), perspective drawing of the

other end ran a double row of pear trees. In the summer

kitchen garden at The Mount, 1901. (College of Environ-

of 1902, when the house was nearing completion but

mental Design Documents Collection, University of Califor-

before they moved in, Edith came nearly every morn-

nia, Berkeley)

18

210

THE GREAT GOOD PLACE

Dolphin fountain in the

flower garden, surrounded

with white petunias. (Bei-

necke Library)

Edith Wharton's friend Walter Berry posing

as a statue with one of her dogs in the trellis

niche designed by Ogden Codman, ca. 1904.

The niche had been moved to The Mount

from Mrs. Wharton's Newport garden. (Bei-

necke Library)

Edith Wharton at The Mount

2II

out of doors the scene is depressing. There has been

shade from pale rose to dark red, it looks, for a fleeting

an appalling drought of nine weeks or more, & never

moment, like a garden in some civilized climate.

has this fresh showery country looked SO unlike itself.

The dust is indescribable, the grass parched & brown,

The Whartons never reached The Mount before

flowers & vegetables stunted, & still no promise of

June, and the weeks in midsummer when the phlox was

rain. You may fancy how our poor place looks, still in

in bloom may have been the most brilliant season in the

the rough, with all its bald patches emphasized. In addi-

garden.

tion. our good gardener has failed us, we know not why,

A highlight of the Lenox social season was the Mid-

whether from drink or some other demoralization, but

summer Flower Show. Edith Wharton worked with the

after spending a great deal of money on the place all

committee on arrangements and fretted over her own

winter there are no results, & we have been obliged to

entries, tying and labeling little clusters of flowers,

get a new man. This has been a great blow; as we can't

many of them raised in her small greenhouse. She was

afford to do much more this year-I try to console my-

competitive, anxious to do well in this field as in every

self by writing about Italian gardens instead of looking

other aspect of her life. In 1906 she was delighted when,

at my own. 26

as usual, she won a bundle of first prizes for her phlox,

snapdragons, lilies, poppies, and gladioli. In her diary,

The new head gardener, Reynolds, was a great suc-

Edith noted the number of first prizes she had collected

cess; he and Mrs. Wharton got on well. Despite the

at the flower show and on the next page the number of

drought, she and Reynolds and his crew planted the

weeks that her new novel, The House of Mirth, had

leighty-by-one-hundred-foot flower garden below the

been the best-selling book in New York. 28 One might

house. In the center of the garden was a pool with a

assume that both accomplishments were equally grati-

spouting dolphin fountain. At the far end was an arched

fying to her.

trelliswork niche that Codman had designed for the

Daniel Berkeley Updike, a frequent and charmed re-

Whartons' garden in Newport. The garden was filled

cipient of the hospitality of The Mount, had mixed feel-

with rosy-colored flowers. The terrace and the room

ings about his hostess's avid gardening:

above, where Edith Wharton wrote each morning, over-

looked the glowing flower garden far below.

Edith was very learned about gardens, and she and a

The friend who best understood and shared Edith

neighbor, Miss Charlotte Barnes, used to hold inter-

Wharton's passion for plants and gardening was Sara

minable, and to me rather boring, conversations about

Norton. Miss Norton was a daughter of Charles Eliot

the relative merits of various English seedsmen and the

Norton, an eminent professor of art history at Harvard

precise shades of blue or red or yellow flowers that they

and a translator of Dante's Divine Comedy. In summer

could guarantee their customers.

Edith was con-

the Nortons lived simply on an old farm in Ashfield, a

scious of my half-hearted interest in horticulture, and

small town in the Berkshires that was removed from

on one particularly dull autumn afternoon when she

Lenox by miles but even more by its utter lack of pre-

was directing some planting, I asked her if there was

tense. Edith described her flower garden to Sara Nor-

not something I could do-hoping that there wasn't!

ton in 1905, urging her to come to see it:

With a malicious glint in her eye she replied, "Yes, you

can pick off the withered petunias that border the foun-

[My garden] is really what I thought it never could be-

tain." If you have ever tried that particular task you will

a "mass of bloom." Ten varieties of phlox, some very

realize the punishment inflicted.

gorgeous, are flowering together [by August, thirty-

two varieties were in bloom], & then the snapdragons,

From the terrace at The Mount a grand double stair-

lilac & crimson stocks, penstemons, annual pinks in

case led down into the garden. The flower garden on

every shade of rose, salmon, cherry & crimson-the

the left was balanced visually by a sunken garden on the

Hunnemania [a yellow Mexican poppy], the lovely

right. The two gardens were linked by a straight gravel

white physostegia, the white petunias, which now form

walk, bordered by lindens. On a slope around the cor-

a perfect hedge about the tank-The intense blue Del-

ner of the house was Edith's rock garden, where she

phinium Chinense, the purple & white platycodons,

grew sun-loving alpines between natural outcrops of

& c.-really with the background of hollyhocks of every

limestone.

212

THE GREAT GOOD PLACE

The flower garden at The

Mount, as seen from the

terrace at the house, 1905.

(Beinecke Library)

Still shuttling architects, Edith Wharton had Francis

terrace that overlooked "a landscape tutored to the last

Hoppin return to The Mount in 1905 to design steps

degree of rural elegance. In the foreground glowed the

and walls for the sunken garden. She wrote Sara Nor-

warm tints of the gardens. Beyond the lawn, with its

ton, "Did I tell you that we are building a high wall

pyramidal pale-gold maples and velvety firs, sloped

around the sunk garden? It will be charming when it is

pastures dotted with cattle; and through a long glade

quite 'tapisse' with creepers. "30 The shadowy walled

the river widened like a lake under the silver light of

garden echoed with the cooling plash of water falling

September."31

from a single jet. Edith knew from her experience of

Edith Wharton's description fit the scene spread out

Italian gardens how welcome were shade and the sight

before her as she wrote. It was the view from the house

and sound of water in the heat of the day. And how re-

that held meaning for her; house and landscape were

freshing was a view: tall arched openings in the wall re-

parts of one felicitous whole. She conveys this sense of

vealed the countryside beyond.

the harmony she had evoked in a passage from Sanctu-

In The House of Mirth (1005). the novel that was

illy's a novella she wrote in 1903: "The large coolness of

Edith Wharton's first large success, her doomed hero-

the room, its outlook over field and woodland to-

ine, Lily Bart, wanders off during a house-party week-

ward the lake lying under the silver bloom of Septem-

end to lean pensively against the balustrade of a broad

ber: the very scent of late violets in a glass on the writ-

Edith Wharton at The Mount

213

ing table; the rosy-mauve masses of hydrangea in tubs

Wharton. After this the growth of plants was linked,

along the terrace; the fall, now and then, of a leaf

for Edith, to sexual awakening. Her novel, Summer;

through the still air-all, somehow, were mingled in the

published in 1916, is filled with erotic metaphors: "the

suffusion of well-being."33

crowding shoots of meadowsweet and yellow flags

A biographer of Beatrix Farrand, prejudiced perhaps

this bubbling of sap and slipping of sheathes and ca-

in favor of her subject, castigated the garden Edith

lyxes." Flowers sometimes represented physical passion.

Wharton made without her niece as "a designed disas-

"Under his touch, things deep down in her struggled to

ter" that appeared to be "stretched on a rack. "33 There

the light and sprang up like flowers in the sunshine."3

is more than one angle of vision, but this one seems to

To Fullerton she compared her efforts as a gardener to

ignore the view and the setting. With her keenly devel-

her writing: "[T]he place is really beautiful.

I was

oped visual sense, her self-confident taste, and her years

amazed at the success of my [efforts]. Decidedly, I'm a

of studying gardens in Italy and elsewhere, Edith

better landscape gardener than novelist, and this place,

Wharton was quite capable of arranging the landscape

every line of which is my own work, far surpasses the

about her house in such a way as to please herself and

House of Mirth.

others. She no longer needed the help of the talented

Not everyone understood Edith Wharton's direct

Beatrix, who seems never to have returned to The

and intimate connection with her garden. She was much

Mount after 1901, when she had planned the entrance

amused by a review in the Atlantic, which stated that her

drive and the kitchen garden. Edith urged Trix to visit

book on Italian villa gardens made it clear that she had

in July 1903, to recuperate from an appendectomy, but

"never worked in a garden!!!"+1 The reviewer was con-

there is no indication that she came. Even if she had,

vinced that "Mrs. Wharton has never spent an hour in a

she would have been unable to work. "[T]his house has

garden uprooting weeds, hunting rose-bugs, squashing

been a hospital all summer," Edith told Sara Norton in

caterpillars.

She betrays no acquaintance with the

early August while Teddy was in a state of collapse.

trowel and a broken back

the heat and sweat of

Beatrix or her mother (Edith's sister-in-law, Minnie

noon. "+42 This was SO far from the truth that it made her

Jones) would occasionally propose over the next few

laugh, but some who actually visited Edith Wharton's

summers to bring the other to The Mount to conva-

garden came away feeling that it lacked the owner's per-

lesce from nervous illness, but Mrs. Jones seems always

sonal touch. Ironically, the very perfection she strug-

to have come alone. 35

gled SO hard to achieve made it seem less than perfect to

Edith Wharton was intimately involved with her

some observers. In her book on the gardens of well-

garden, from its overall design to "every tiniest little

known people, Hildegarde Hawthorne complained that

bulb and shoot." Each time she returned to Lenox in

Mrs. Wharton's garden lacked "intimate charm

the

June after a winter's absence, she would walk through

sense of personal and loving supervision," in contrast to

the garden with Reynolds, her head gardener, checking

the "special spiritual quality" emanating from Mrs. Jack

to see how each "tree, shrub, creeper, fern, 'flower in

Gardner's garden at Green Hill in Brookline, for exam-

the crannied wall' had come through the winter.³6

ple.43 Sara Norton's sister Lily found The Mount quite

Sometimes she was dismayed. Her emotional attach-

chilling: "Her house, her garden, her appointments

ment was such that she suffered when her garden suf-

were all perfect-money, taste, and instinct saw to every

fered. 37 During recurrent "cruel" droughts, she ago-

detail; yet the sense of a home was not there."

nized over "parched grass and starved skinny trees."

Daniel Chester French and his wife, Mary, who had

She raged at the hill-country winters that interfered

made their own garden at Chesterwood, perceived

with her gardening plans and injured her plants. "Even

more clearly Edith Wharton's artistry. Her place, with

the clematis paniculata I had established SO carefully is

its view "like an old tapestry," was, according to Mrs.

dead," she wailed one spring. Another year she cried,

French, "one of the most exquisite to be found any-

"Don't talk to me about this climate! I don't think any-

where in the Berkshires. "44 Edith Wharton visited the

thing has grown an inch since last year. "38 She pined

for

Frenches' garden, and they came sometimes to The

a more "civilized climate" than that of the region she

Mount. Mrs. French described how "when we went to

had chosen.

her place, she and Mr. French would wander about the

Morton Fullerton visited The Mount in October

grounds, exchanging ideas, she courteous enough to ask

1907, setting the stage for a passionate affair with Edith

his advice, but artistic enough to need little from any

214

THE GREAT GOOD PLACE

one." The Frenches considered The Mount a model of

The more involved and successful Edith Wharton

"what can be done in landscape gardening by develop-

became as a writer, the more she was drawn to friend-

ing every little natural beauty, instead of going in with

ships with artists and intellectuals. Teddy Wharton, in-

preconceived ideas and trying to make it like some

creasingly cantankerous. was left out. His wife's friends

other beautiful place to which the lay of the land bears

often found him as trying as he found her literary life.

no resemblance whatever."

To Charles Eliot Norton he wrote, "I should like you to

see 'The Mount,' to prove to you that Puss [Edith's

nickname] is good at other things besides her to me

rather clever writing."

In a letter to a friend, Edith Wharton described the

The Whartons found one mutual interest when they

daily routine at The Mount: "Here I write every morn-

acquired their first automobile in 1904, "a little sputter-

ing, & then devote myself to horticulture, while Teddy

ing shrieking American motor in which we hope to see

plays golf & cuts down trees." This may have been

something of the country."+7 How difficult it is to imag-

how she thought she would like to spend her days, but

ine the sense of liberation that the first motorcars

her account bore little resemblance to reality. In fact,

brought to their privileged owners. Edith Wharton

such a disciplined and solitary life would not have suited

thrilled at "the escape from the railways, the charm of

her, for by choice she led such an overwhelmingly social

exploring new roads, of being able to flit from point to

existence that her steady literary output seems miracu-

point as the fancy takes us."+8 With their chauffeur,

lous. The writing was done early, in the privacy of her

Charles Cook, Teddy Wharton beside him, and accom-

own room. Serious gardening followed, as she said. But

panied at the best of times by her new friend Henry

always there were friends coming to stay, servants to

James, Edith Wharton whirled over the hills and val-

manage, guests for lunch or dinner, meals to plan, and

leys of New England, each year in a new and more pow-

letters to write. Her little dogs-Miza, Jules, Nicette-

erful car.

clamored for attention. Then Mrs. Wharton would dash

The Whartons introduced Henry James to the mo-

off to a committee meeting or a social call. The Whar-

torcar. Both he and the motor figured largely in Edith

tons traveled continually: to Europe and to New York

Wharton's life at The Mount and in the meaning the

as a matter of course, but even when supposedly settled

place held for her. James, then in his sixties and at the

at Lenox, they would frequently depart for a few days

peak of his literary powers, paid three visits to The

visit here or a week there.

Mount. At that beautiful place and on their motor

The Whartons' motorcar at

The Mount, 1904. Edith

Wharton and Henry James

are seated in the back, with

chauffeur Charles Cook at

the wheel and Teddy Whar-

ton beside him. (Lilly Li-

brary, Indiana University)

Edith Wharton at The Mount

215

"flights" over the countryside, he was in some measure

The view from the terrace at The Mount, toward Laurel

consoled for the depressing changes he had found on

Lake and the Tyringham hills. ca. 1905. (Beinecke Library)

his return to his homeland after twenty years abroad. "I

have been won over to motoring, for which the region

is, in spite of bad roads, delightful."+9 As they spun

along through the glorious autumn afternoons, amid

Sprague at Faulkner Farm in Brookline and visited the

colors "like molten jewels," James was overwhelmed by

Thayers gardens in Lancaster.

"the sweetness of the country itself. this New England

Riding through the back country, away from the re-

rural vastness."

sorts of the prosperous. both Henry James and Edith

For Edith Wharton, too, motoring provided "an im-

Wharton were struck by the bleak desolation of lonely

mense enlargement of life."50 By motor they drove

farmsteads and villages. Even in summer the starved as-

often to visit the Nortons in Ashfield, trying different

pect of New England's hinterland was a reminder of the

routes through the hill country. One day they drove to

long months of wintry chill, against which Edith Whar-

Litchfield, Connecticut, a town that charmed James.

ton SO fruitlessly railed as it affected her garden. Out of

()n a jaunt to Cornish, New Hampshire, the Whartons

her sense that the weathered gray facades were prisons

visited the Maxfield Parrishes and others in that colony

of a sort. she wrote of desperation and hopeless entrap-

of artists and gardeners. On longer motor trips, Edith

ment in Ethan Frome and of rural degeneracy in Sum-

Wharton visited more gardens. After lunching one day

mer. The barren lives of her characters were ostensibly

in 1005 with the Coolidges at the old Governor Ben-

the reverse of her cushioned existence, but as her hus-

ning Wentworth place near Portsmouth, New Hamp-

band's mental state deteriorated. her own life became SO

shire. the Whartons drove on to tea with Mrs. Tyson at

fraught with uncertainty and anguish that she may her-

Hamilton House. Another time they called on Mrs.

self have felt imprisoned. The Mount itself became one

216

THE GREA T GOOD PLACE

of the complexities of her life as her husband and her

Late into the moonlit night, James held as charmed

marriage disintegrated.

captives the little "inner group" of friends while he spun

tales and evoked visions of his lost youth. 54

The Mount had to be sold. After too many scenes,

too many arguments over money, too many unsuccess-

One of Henry James's stories, "The Great Good Place"

ful attempts to mend Teddy Wharton's mind, Edith

(1900), still strikes a responsive note in those who have

Wharton finally concluded that life with him was im-

felt the frantic despair of the protagonist, a man beset

possible. She could no longer afford to keep The

and bound by a web of worldly concerns, a web no less

Mount, with or without Teddy. In September 1911, she

constricting for his having woven it himself. In a vivid

left Lenox for the last time and sailed for France. The

dream he finds himself at a place of peace and beauty,

Mount was sold in 1912. The Whartons were divorced

where hours of solitude are spent in the serenity of a

in 1913. Edith Wharton lived in France for the rest of

fine library, and companionable hours are passed in

her life, making there two homes for herself and two

conversation of a high order. James may have thought

memorable gardens.

of this as an ideal spiritual state or as a vision of what

The house and gardens at The Mount are being re-

civilization at its best might be. While staying at a for-

stored now, thanks to the timely intervention of Edith

mer monastery in France in 1910, Edith Wharton felt

Wharton Restoration, Inc. The view has been recov-

that she had found James's Great Good Place. 52 All her

ered; garden walls and walks have been reclaimed.

efforts at The Mount had been directed toward mak-

From her terrace, on' an autumn afternoon, the ideals

ing such a place of her own. For a few years she suc-

of harmony, proportion, and beauty that inspired Edith

ceeded, balancing creative work with social intimacy in

Wharton seem distinctly possible. She came quite close

a beautiful and harmoniously ordered setting of her

to achieving her goal at this great good place.

own making.

Writing to Bernard Berenson in I9II, Edith Whar-

ton summed up her delight in her "really beautiful"

place: "the stillness, the greenness, the exuberance of

my flowers, the perfume of my hemlock woods, & above

Notes

all the moonlight nights on my big terrace, overlooking

the lake." The terrace was the focus of The Mount,

where, on precious fleeting occasions during her ten

I. Edith Wharton, A Backward Glance (New York: Apple-

years there, her ideal was made real. From "that dear

ton-Century, 1934), 124. Biographies of Edith Wharton in-

wide sunny terrace" she and those she loved could feast

clude R. W. B. Lewis, Edith Wharton (New York: Harper &

their eyes on the landscape she had composed with just

Row, 1975), and Eleanor Dwight, Edith Wharton: An Extraor-

this vantage point in mind. The view of the gardens,

dinary Life (New York: Abrams, 1994).

woods, lake, and hills soothed her mind and spirit.

2. Edith Wharton (hereafter cited as EW) to Ogden Cod-

Evenings too brought serenity: "I went out on my ter-

man Jr. (hereafter cited as OC), I August 1900, Codman Fam-

race last night, and took up my interrupted communion

ily Manuscripts Collection, Society for the Preservation of

with Vega, Arcturus, and Altair." One night "the terrace

New England Antiquities (hereafter cited as CFMC), box 84.

was saturated with real white moonlight, & it was hot

3. Picturesque Berkshire (Northampton, Mass.: Picturesque

enough to sit out late & listen to the Aristophanes cho-

Publishing Co., 1893), 22.

rus in the laghetto."53

4. George A. Hibbard, Lenox (New York: Charles Scrib-

On the terrace, Edith Wharton also found social

ner's Sons, 1896), 35-38.

communion of the highest order, justifying all her ef-

5. EW to OC, 27 September 1900, CFMC, box 84. See

forts at The Mount. The memory of one evening in

Edwin Hale Lincoln, A Pride of Palaces, ed. Donald T. Oakes

particular stayed with her, "when we sat late on the ter-

(Lenox, Mass.: Lenox Library Association, 1981).

race with the lake shining palely through dark trees." In

6. OC to Sarah Bradlee Codman, 25 February 1901 and I

response to an allusion to his Albany relatives, his "laby-

July 1901, CFMC, box 50.

rinthine cousinship," someone asked Henry James to

7. Daniel Berkeley Updike. quoted in Percy Lubbock, Por-

"tell us about the Emmets--tell us all about them."

trait of Edith Wharton (New York: Appleton-Century, 1947),

Edith Wharton at The Mount

217

17-18; EW to Sara Norton, 23 August 1905, folder 6, Edith

33. Jane Brown, Beatrix: The Gardening Life of Beatrix Jones

Wharton Papers, Beineke Library, Yale University.

Farrand, 1872-1959 (New York: Viking, 1995), 79.

8. Richard Guy Wilson, "Edith and Ogden: Writing, Dec-

34- EW to Sara Norton, 9 August 1903, folder 4, Wharton

oration, and Architecture," in Ogden Codman and the Decora-

Papers.

tion of Houses, ed. Pauline C. Metcalf (Boston: Boston Athe-

35. EW to Margaret Terry Chanler, 7 September 1902;

naeum, 1988), 164.

EW to Sara Norton, 5 June 1903, 23 September 1906, 26 Oc-

9. OC to Sarah Bradlee Codman, I7 February 1901,

tober 1906, folders 4 and 7; EW diary, 24 October to 5 No-

CFMC, box 50.

vember 1906, Wharton Papers.

IO. OC to Sarah Bradlee Codman, 7 February 1901,

36. EW to Morton Fullerton, 3 July I9II, in The Letters of

CFMC, box 50.

Edith Wharton, ed. R. W. B. Lewis and Nancy Lewis (New

II. EW to OC, 25 March 1901, CFMC, box 84.

York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1988), 242.

I2. OC to Sarah Bradlee Codman, 3 March 1902, CFMC,

37 Judith Fryer, Felicitous Space: The Imaginative Structures

box 50.

of Edith Wharton and Willa Cather (Chapel Hill: University of

13. OC to Sarah Bradlee Codman, 5 October 1902,

North Carolina Press, 1986), I75.

CFMC, box 50.

38. EW to Sara Norton, I7 June 1905 and I4 June 1906,

14. OC to Sarah Bradlee Codman, 8 June 1905, CFMC,

folders 6 and 7, Wharton Papers; 3 July I9II, No. IOI5, Nor-

box 50.

ton Family Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

I5. Updike, in Lubbock, Portrait of Edith Wharton, I7.

39. Edith Wharton, Summer (New York: Signet Classic,

16. OC to Sarah Bradlee Codman, 8 October 1902,

Penguin, 1993), 33-34, I22.

CFMC, box 50.

40. EW to Morton Fullerton, 3 July I9II, Letters of Edith

I7. Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman Jr., The Decoration

Wharton. 242.

of Houses (1897; reprint, New York: W. W. Norton, 1978), 22,

4I. EW to Sara Norton, 2 August 1906, folder 7, Wharton

49.

Papers.

18. Updike, in Lubbock, Portrait of Edith Wharton, 20.

42. Henry Dwight Sedgwick, The New American Type and

19. Edith Wharton, Italian Villas and Their Gardens (1904;

Other Essays (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1908), 73.

reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1988).

43. Hildegarde Hawthorne, The Lure of the Garden (New

20. Edith Wharton, "The Line of Least Resistance," in

York: Century, 1911), 135-36.

The Stories of Edith Wharton, ed. Anita Brookner, (New York:

44. Elizabeth G. Norton, quoted in Lubbock, Portrait of

Carroll & Graf, 1989), 2:35.

Edith Wharton, 40.

21. Wharton, Italian Villas, IOI.

45. Mrs. Daniel Chester French, Memories of a Sculptor's

22. EW to OC, 29 July 1901, CFMC, box 84.

Wife (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1928), 205.

23. EW to Sara Norton, 7 June and + July 1902, folder 3,

46. EW to Mrs. Alfred Austin, 14 August 1906, Letters of

Wharton Papers.

Edith Wharton, 107-8.

24. OC to Sarah Bradlee Codman, 8 October 1902,

47. EW to Sara Norton, I2 July 1904, folder 5, Wharton

CFMC, box 50.

Papers.

25. EW to Sara Norton, 30 September 1902, folder 3,

48. EW to Sara Norton, 24 January 1904, folder 5, Whar-

Wharton Papers.

ton Papers.

26. EW to Sara Norton, 5 June 1903, folder 4, Wharton

49. Henry James to Jessie Allen, 22 October 1904; Henry

Papers.

James to Edmund Gosse, 27 October 1904, in Henry James's

27. EW to Sara Norton, 23 July 1905, folder 6, Wharton

Letters, ed. Leon Edel (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univer-

Papers.

sity Press, 1984), 4:329.

28. EW diary, I5 August 1906, Wharton Papers.

50. Wharton, Backward Glance, 176.

29. Updike, in Lubbock, Portrait of Edith Wharton, 19-20.

5I. EW diary, 27 August and 29 October 1905, 29 June

30. EW to Sara Norton, 26 October 1907, folder 8, Whar-

1906, Wharton Papers.

ton Papers.

52. Lewis, Wharton, 291.

3I. Edith Wharton, The House of Mirth (1905; reprint,

53. EW to Margaret Terry Chanler, 18 July 1903, Whar-

New York: New American Library, 1964), 52.

ton Papers.

32. Edith Wharton, Sanctuary (New York: Charles Scrib-

54. Wharton, Backward Glance, 192-94:

ner's Sons, 1903), 86.

218

8 THE GREAT GOOD PLACE

SOUTHERN NEW HAMPSHIRE

UNIVERSITY

26 December 2003

Ms. Alan Emmet

224 Concord Road

Westford, MA 01886

Dear Ms. Emmet:

Nini Gilder suggested that I contact you regarding your research on Edith Wharton at the

Beinecke and its relationship to my own inquiries.

For the last three years I have been involved in research for an intellectual biography of

George B. Dorr. My research is focused on the manuscript collections that have been

almost entirely ignored by others who have written about the founder of Acadia National

Park. While the National Archives, Rockefeller Archive Center, and other repositories

have been expansive in documenting the last forty years of his life, Mr. Dorr's first fifty

years are more challenging to the biographer due to the paucity of surviving documents.

Ms. Gilder's e-mails over the last year have been enormously helpful in tracing the

Lenox connections between the Dorr and Wharton family. In her October 7th e-mail she

mentions your interest in the Mt. Desert Nurseries and alludes to your investigation of the

Dorr-Wharton correspondence at the Beinecke. I plan to travel to New Haven in the next

few months to pursue this matter but I wondered whether you would share with me any

insights and impressions drawn from your inquiries into Mr. Dorr. Has there been an

archivist at the Beinecke that has been most helpful to you? In turn, I will gladly share

with you any documentation I've gathered of the Mount Desert Island gardens developed

by Mr. Dorr and his mother Mary, Beatrix Farrand, Abby Rockefeller, Charles Savage,

etc.

I'm wondering whether you made use of the 1881-1901 gardening committee minutes of

the Bar Harbor Village Improvement Society at the Jesup Memorial Library for your So

Fine a Prospect which I have not yet consulted.

Wishing you holiday greetings and best wishes for the New Year.

Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

Director of the Shapiro Library

e-mail: r.epp@snhu.edu

Home phone in Merrimack: 603-424-6149

New Hampshire College is now Southern New Hampshire University

Harry A. B. & Gertrude C. Shapiro Library

2500 North River Road Manchester, NH 03106-1045 603-645-9605 Fax 603-645-9685

ALAN EMMET

224 CONCORD ROAD

27 Jan. 2004

WESTFORD, MASSACHUSETTS 01886

(978) 692-8329

Ronald H. Epp, Ph. D.

Director, Shapiro Library

Southern New Hampshire University

2500 North River Road

Manchester, NH 03106-1045

Dear Dr. Epp,

Finally, in response to your 26 December letter regarding your research on George B.

Dorr. Perhaps my suggestions are by now superfluous.

1. Regarding the Wharton collection at the Beinecke Library at Yale:

YCAL 42

Box 24

Folder 753

Correspondence between EW and GBD, 1902-1906

Dorr visited Lenox in 1904 and 1905. She sought his advice; refers to the "George B.

Dorr path," the new pond and other improvements, suggested, I gather, by him. She asks

him to have his manager send her the name and colour of good new varieties of phlox.

My duplicate copy of one letter is enclosed.

2. See (as you probably have) The Story of Acadia National Park; Memoirs of George B.

Dorr (reprinted).

3. The Bar Harbor Historical Society has Dorr's papers, but from two sources I was told

they contained no references to Wharton.

4. National Geographic 26: 74-89 (July 1914) "The Unique Island of Mt. Desert", GBD

et alia

5. Nature Magazine (May 1929: 315-18 & 345, "Acadia N. P.", GBD

6. I suggest calling Partrick Chasse, Landscape Design Associates

phone 617-628- 1757 or 617-628-9238

Through him you might see a Mt. Desert Nursery catalog or other helpful material.

I never saw the Bar Harbor Village Improvement Society's records. This is really all I can

offer, but I wish you luck in your research and with your biography. His early life is a

blank to me, but well worth finding out about.

Sincerely,

Alan Tenmet

21 Fenruary 2010

Ms. Alan Emmet

224 Concord Road

Westford, MA 01886

Dear Ms. Emmet,

In Massachusetts Audubon's Connections, I ran across an all too brief article on the

generosity of the Emmets in establishing the lovely Nashoba Brook Wildlife Sanctuary.

It reminded me that I had been remiss in keeping you abreast of my progress in

completing the biography of Acadia's founder, George Bucknam Dorr. Two months ago

the final half of the manuscript was delivered electronically to the publisher, Robin

Karson at the Library of American Landscape History. I'm now responding to chapter-

by-chapter editorial revisions and selecting illustrations. After a decade of research and

writing I feel much relieved to have it out of my hands.

In our earlier communications we had speculated about lunch in Westford at a place

convenient to you. As Spring approaches, I am renewed with hope that we can realize

this objective. I'm free most days in the last two weeks of March, if you'd like to propose

dates and location. I'd like to show you a copy of Edith Wharton and the American

Garden, the fruits of the conference held at The Mount three years ago.

I look forward to hearing from you. Do you have email?

Most Cordially,

Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

47 Pond View Dr.

Merrimack, NH 03054

603-424-6149

Eppster2@myfairpoint.net

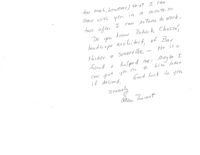

you about the date of Patrick

March 28,2010

Chasse's talkat the Gardner,

which had already occurred.

Dear Dr. Epp,

I'M sorry.

I'm still reading your

It was a great pleasure

copy of the new book on

to meet you, and enjoy

Edith whaton but will

lunch with you. Thank

mail it back soon.

you so much. we

I hope you weren't too

had so much to tack

shocked by my tale of

about. I look forward to

being kicked out of

your book on George

Memphis! at least my

Dorr. what fascinating

two boys did not turn

paths he has led

into handened criminals.

you down!

Sincerely.

I realize I misled

Alau Emmet

Page 2

Westford Conservation Trust Newsletter

Fall Walk

Dick S. Emmet

1924-2007

Saturday,

"Go forth, under the

October 20th

open sky, and list to

Nature's teachings,

9-11am

while from all around--

Richard Emmet Conservation Land, Trailside W ay

Earth and her waters,

Join Trust Directors Lenny Palmer and Paul Cully

and the depths of air-

comes a still voice". -

on an exploration of this beautiful area of protected

Thanatopsis by

open space. This should be a wonderful walk, at the

William Cullen Bryant

height of fall foliage. Wear sturdy shoes as the area

is relatively flat but rocky. This walk is appropriate

In memory of Trust member and Vice President

for all ages, but area is not suitable for strollers. No

Emeritus Dick Emmet, we mourn the passing of

dogs, please. Park at the Town parking area off the

such a wonderful intelligent, talented and engaging